![]()

Chapter One

CAMBODIA:

TIGHTLY CONTROLLED BY THE CAMBODIAN PEOPLE’S PARTY

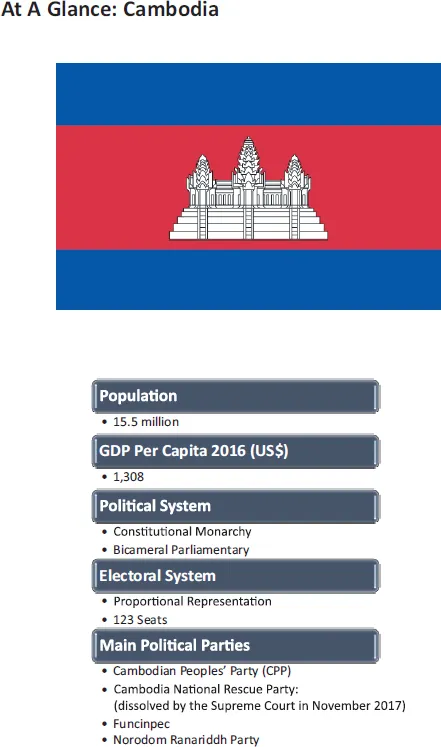

Among the three countries which have formed what was once known as French Indochina, Cambodia has suffered the longest period of turmoil and violence. Decolonized and independent since 1953, the country could not avoid being drawn into the Vietnam War and was heavily bombed by the United States. After the end of the war, for another four years from 1975 to 1979, Cambodia crippled herself under the atrocious rule of Pol Pot’s stone-age Communism. The Khmer Rouge terror ended through an invasion by Vietnam which delayed the recognition of the new state by the international community. Only after the Paris Peace Accords of 1991 and the UN-supported election (UNTAC) in 1993, the country started to recover from external and internal violence and to slowly reconstruct the nearly completely destroyed economy and infrastructure. In September 1993, a new constitution established a multi-party democracy within a constitutional monarchy. Already prime minister under Vietnamese tutelage since 1985, Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge cadre, dominated the domestic political scene and managed to out-manoeuvre all competitors until today. His Cambodian People’s Party, under this name since 1991, has its roots in the Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party and has kept some of the latter’s communist organizational elements.

The ruling CPP with its communist and revolutionary roots has an inherent propensity of controlling the state as much as possible in a country under reconstruction with a big majority of the population still living in the rural areas. The CPP has co-opted the public service to a very high degree, subjecting civil servants to party membership and strict hierarchical control. It has practically unlimited access to funds by blurring the line between state and party. Since the business sector is dependent on the state bureaucracy, the party-affiliated cronies can enrich themselves, but are also expected to fund public projects like schools or bridges, which are then accredited to the CPP government. Prime Minister Hun Sen is famous for his precise memory, and for the special way he turns around during a speech to pick the local dignitary who he knows is rich enough to shoulder the funding of the project that was just promised to the local community.

War-torn Cambodia has, despite the general poverty, attractive resources for exploitation. Besides the last precious tropical timber, which is officially protected but has disappeared rather fast during the last decades, the biggest source of income was land concessions rented out to well-connected Cambodians and foreign investors for up to 100 years. Estimations of the total area of the concessions go up to half of the arable land, which threatens the livelihood of hundreds of thousands of small farmers who are often evicted, and creates support for the opposition which offers help in the countless land disputes.

Cambodia has also profited from enormous amounts of foreign aid, which was partly triggered by the international optimism after the successful UNTAC intervention and election in 1993, in hopes that the country would follow the path towards Western style democracy instead of getting closer to China. In the meantime, and after numerous disappointments over the domestic political developments under Prime Minister Hun Sen’s iron fist, the U.S. and European donors are seriously starting to re-evaluate their commitments.

How exactly the financial connections between the government machinery and the CPP work remains often enough in the dark, and it does so, of course, by design. However, there is enough evidence about a rather sophisticated solution to the party funding problem which allows the government to make donations look legitimate, if not legitimising them altogether. Businessmen who donated US$100,000 or more to the CPP got, in return, lucrative government contracts or licenses to extract natural resources. On top of that internationally all too common reward, they are bestowed the honorary title of “Oknha” by the royal family, after having been identified and chosen by the CPP leadership, especially by Prime Minister Hun Sen himself. The number of “Oknhas” has multiplied with the country’s economic recovery; in 2014, there were already 700 of them, up from only 30 a decade ago.1 During the last few years, there were obviously so many aspirants that the party could increase the minimum donation to US$500,000 in early 2017. The Oknha title stands for prestige and status, but does not necessarily reflect full-fledged political support for the CPP. Like in most other countries, it promises to secure political backing and contracts, but is also a part of business strategies for survival in the growing market. What the Oknhas seem to share with the CPP policies, though, is skepticism and avoidance of a regime change, which might bring more uncertainties for their businesses. As long as the ruling party can guarantee lucrative deals, in which the donations can be factored in as expenses, maybe even tax deductible, the pact will work. With this type of symbiotic arrangements, Cambodia’s CPP can probably compete with Malaysia’s UMNO as the best funded political party in Southeast Asia and beyond.

Two very detailed reports by the UK-based non-governmental and not-for-profit organization Global Witness2 describe the depletion of the remaining tropical timber and the progressing exploitation of mineral reserves, with many political and military figures securing the concessions and control of the companies involved.

The mining and oil exploitation is a telling example of how the political establishment under Hun Sen has secured control of the proceedings. The Cambodian National Petroleum Authority (CNPA), created by royal decree in January 1998, took over the responsibility for the oil and gas sector from the Ministry of Industry, Mines, and Energy, and is run by pro-Hun Sen CPP politicians.

An additional source of income, certainly for the state budget but possibly for the party as well, is the growing involvement of China in the Cambodian economy. Trade between the two countries, though very lopsided in favour of China, has grown to nearly US$5 billion per year, and Chinese investment in the new Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone alone reached US$3 billion. For the regime, which has played out the Western donors against each other for many years, money from China is more attractive as it comes without conditions and strings, and no unpleasant discussions about democratic development and human rights, as well as with very soft loans or unconditional debt relief. On the other side, Hun Sen vehemently rejects president Trump’s renewed demand to pay for a “dirty debt” of US$500 million from the early 1970s. Cambodia, being a welcome and useful ally for China, with her role as an ASEAN member, and supporter in the South China Sea controversy, the big neighbor is getting substantially invested in agriculture, industry, energy, and tourism, and outperforming the traditional and rather generous Western donors altogether. During the last few years, China accounted for 70% of the total industrial investment, and created badly-needed employment in Cambodia. The CPP and its leader are a guarantor for stable bilateral relations, and internal observers suspect Chinese largesse as contributing to the finances of the ruling party accordingly.

Global Witness is also exposing the business activities of the Hun Sen family. According to the report quoted above, the Prime Minister’s immediate family has registered interests in 114 private domestic companies with listed capital of more than US$200 million, mostly as chairpersons, directors, or major shareholders. These companies have business connections to the biggest international names and global brands. When Hun Sen first declared his assets in 2011, he was quoted as saying that apart from his official salary US$13,800 per year, he did not have any other income, but hoped that his children would support him and would not let him starve… That was taken as a lie by some Western journalists, but it was, of course, not more than a somewhat cynical joke.

The Prime Minister’s way of charging infrastructure investments for the public benefit to his enriched supporters is a clever and logical consequence of the symbiotic interconnectedness between the political, military, and business elites. Their ostentatious lifestyle, and their pompous and palace-like villas in the capital, as well as their flashy SUVs, which even carry the brand name in added huge characters on the sides, are probably a political, or at least a communication mistake. It only angers the disenfranchised majority and helps the opposition’s popularity. Even in Suharto’s Indonesia, the cronies were admonished to keep their villas less conspicuous.

The Global Witness’ “Hostile Takeover” report quotes a U.S. government cable from the U.S. embassy in Phnom Penh to several government departments in Washington, retrieved from Wikileaks and dated August 2007:

The all too obvious interconnectedness and quasi-interchangeability of party and government, has another weak point in the lower ranks of the CPP, like in the Communist Party in neighboring Vietnam. The CPP party membership is estimated at 5.4 million or around 68% of the registered voters, which means that it is understandably, and most probably to a high percentage, opportunistic or forced, as in the overblown public service. The local election in June 2017, in which more than 400 communes have been lost to the opposition, has shown that not all the party members have voted for the CPP. The alarm bells have triggered counter-measures, and a leaked secret paper with the title “The Introduction of Measures for Strategic Implementation: One Member, One Vote” is supposed to initiate an internal survey and control exercise to check on the member’s party allegiance and distribute new membership cards to the reliable ones.4 As if this was not safe enough, the crackdown on the opposition was intensified. In democratic systems, trying to win an election and replace a ruling party is certainly a normal political goal and not a crime, but losing power after more than three decades is a challenge, if the ruling elite enjoys its spoils and privileges as much as it does in Cambodia.

The Opposition

The main opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), was established in 2012 as a merger between the Sam Rainsy Party and the Human Rights Party (HRP). Both used to receive limited donations, mainly from Cambodians abroad. The Sam Rainsy Party Senator, Teav Vannol, who helped to coordinate fundraising for the 2013 national campaign, estimated that about 60% of campaign cash came from the diaspora.5 In unusual transparency and openness, the HRP used to hang the lists of donations from its supporters in the U.S., neatly separated by U.S. states and months, outside their rather humble headquarters in Phnom Penh. The Sam Rainsy Party enjoyed support from Cambodian expatriates and emigres as well, but party president Sam Rainsy is rich enough to fund some activities himself. Apart from Cambodians abroad and crowdfunding inside the country with members and supporters of the CNRP, there are also company donations, even from Oknha who are more critical of the CPP or unhappy with their rewards in contracts and concessions.

The constant flow of donations from the diaspora has obviously whetted the appetite of the CPP to compete with the opposition. West Point-educated Lieutenant General Hun Manet, Hun Sen’s oldest son and chief of the National Counterterrorism Taskforce, tries to drum up support during his travels abroad. Lately, the CPP announced that it has created party branches in India, Indonesia, Japan, Kuwait, the Republic of Korea, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam, and strengthened membership in regions that have Cambodian populations such as Australia, Norway, France, the U.S., and Canada.6

The CNRP has come under heavy pressure because of its successes in the last elections and obvious popular support in a population which seems to be somewhat tired of the Prime Minister and his party. In the 2013 parliamentary election, the CNRP won 55 out of the 123 seats, with 44.5% of the votes.

After Sam Rainsy was already neutralized and went into self-exile in France, the attacks focused on his successor, Kem Sokha, the former leader of the Human Rights Party, who was obviously targeted for elimination as well. On 3 September 2017, he was detained, imprisoned, and indicted for treason and conspiracy by attempting to topple the government with the help of the U.S. On top of these accusations towards the leader, the party is also accused of conspiracy with other foreign players, namely with the Democratic Action Party (DPP) of Taiwan.7 Like the Sam Rainsy Party was affiliated before, the CNRP is a member of the Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats, a 25-year-old loose umbrella organization of which the Taiwanese DPP was a founding member. Their activities were mainly conferences and training of members and thus, financial support among the members is highly improbable.

A controversial new party law, passed with the CPP majority in July 2017, allows for the dissolution of a party if any of its leaders has been convicted of a crime. With the judiciary being flexible and in support of the government, the lawsuits against Sam Rainsy had already shown that the necessary convictions ...