![]()

Chapter 1

Our Current Situation

1.1What key challenges face humanity?

Many recognize the 21st Century is probably a make-it or break-it period for our species. While it might seem implausible that we could wipe out a substantial portion of the global population and radically change biodiversity as we know it on such a short time scale, it is a possibility that we must take seriously. In order to tackle a problem/dilemma of such grand proportions, we must consider ultimate (distal) causes of this potentiality (and, further, distinguish them from proximate ones). With this intent focus in mind, we ask, would we not be better positioned to come to a collective awareness of our future and make the necessary changes so that our civilization averts a multitude of catastrophes?

Before we begin, let us acknowledge that the above is couched in dire terms. Yet, before readers dismiss this work based on this position, as dismal diatribes are a dime a dozen these days, let us point out that we, the authors, do not believe that fear serves as a good motivator for positive change. However, it is not sensible to ignore the gravity of our situation either. We, thus, carry forward with this project with the mindset that humans have the capacity to create a much better future than the reality we now witness.

What are the ultimate causes to the threat of our species impending demise? The threat of climate change is an opportunity to not only avoid mass destruction but to create a flourishing integrated and harmonious society. The obstacles? Capitalism, materialism, imperialism, inequality, overpopulation (which we soon debunk), toxic chemicals, and militarism all come to mind. Racism, sexism/misogyny, xenophobia, homophobia, and cultural chauvinism also deserve mention as complementary factors in such a list. Determining which of these are proximate or ultimate causes of our potential ‘doom’ would be a book unto itself, yet some discussion of them is mandatory if we are going to arrive at potential remedies and solutions. As the saying goes, you cannot fix a problem unless you first understand what is causing it.

At least that is how a logical (rational) person might address these challenges. However, paradoxically, for our purposes, we may not need to know for sure what will be the ultimate genocidal agent. Likely, a multiplicity of agents working synergistically in nefarious ways will be our undoing. In fact, it may be that focusing on ‘doom and gloom’ (as we find occurring in most media outlets these days, both on the right and left of the political center) merely distracts us from more meaningful, purposeful and productive engagement. What if we began to focus on goals first rather than on ‘all the problems’ or ‘all the disharmonies’? Might we, by so doing, refocus/redirect feelings of despair, hopelessness and frustration towards positive-orientated thoughts about capacity, opportunity and progress? What indeed are the collective ideals to which we aspire? And, can these be reached while at the same time avoiding continued global degradation? Notice, if the answer to this last question is ‘no’, then we must return to our goals once again. One might like German chocolate cake the most but when one considers the health impacts of eating it exclusively, one reconsiders if ‘eating blissfully’ is an appropriate goal.

Prioritizing goal setting does not make our work/project any easier. With plenty of options for guidance, there exists one theoretical construct which appears rather compelling as we enter into this radical transition of civilization as we know it — the precautionary principle (PP). Its tenets dictate that we need to proceed with caution when we engage in behaviors/activities that we have reason to think might be harmful to humans, and life more generally. It demands that we consider all the options available to us and that we continually assess and reassess decisions made (and actions taken) to determine if better ways exist to achieve our collective ends.

The PP has been successfully used to craft many policies at the global, national, and local levels. The Science & Environmental Health Network (founded in 1994) has dedicated a lot of work on both the theory and operationalization of PP (an extensive FAQ on PP can be found on the organization’s website: SHEN, 2017). In the context of PP, the ends serve as the goals, and establishing/setting goals becomes a fundamental and commencing act. Humanity could benefit greatly from a deep reevaluation of its goals, something akin to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (passed 70 years ago in Paris) or the Rights of Mother Earth (passed in 2010 by the Bolivian legislative assembly). Along these lines, and for the purposes of furthering discussion, we offer the following as humanity’s goal of the 21st Century:

To provide the highest quality of life to all humans while preserving biodiversity.

Recognizing, of course, that other equally desirable goals could be formulated, our goal is not to pick the ‘best’ one but rather to show how one such goal could act as the organizing principle guiding the grand transition that we all need to make. Other steps exist in the operationalization of the PP (including, ‘exploring alternatives to possibly harmful actions’, ‘placing the burden of proof on proponents of an activity rather than on victims or potential victims of the activity’, and, ‘bringing democracy and transparency to decisions affecting health and the environment’ (PP FAQ, n.d.) and these considerations need consideration as well, but here, identifying the goal is sufficient for our purposes. The remaining chapters of this book focus on identifying viable solutions to our pressing problems and indicating how they are being activated as a prefiguration, a provocation for others to evaluate them in theory and in practice.

Simple but effective, our goal makes it clear that all humans are relevant to any actions taken. On this score alone, most capitalistic activities would be deemed misguided, as maximizing profits necessitates exploitation and oppression. The precept to ‘preserve biodiversity’ demands that we don’t ‘[pave] paradise and put up a parking lot’ (as expressed by Joni Mitchell in the 1970s). It also implies the need to eschew hubris as it relates to an understanding of what is ‘best’ for biodiversity, e.g., many technological fixes have made things worse not better. In other words, the challenge facing humanity this century is to find ways to live in harmony with the biosphere or suffer from its continued breakdown. The fact that most of us (in the USA at least) act as if nature is nothing more than an inconvenience (such as roaches and mice in a house, mosquitos or flies on a patio, ‘weeds’ in our gardens or on a lawn, or squirrels and opossums on a roadway) suggests how far we must still go. More optimistically, thousands of national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been formed to work on this challenge (see Paul Hawken’s Blessed Unrest, or his short video, for an expansive list; Hawken, 2007). And while this ecologically-centered movement manifests and should, if fully actualized, ward off the most damaging and destructive activities, it takes as its first premise that the goal is to focus on our core aspiration — to enhance the lives of humans to their fullest.

How does one provide the highest quality of life? What does this mean? Is it not strange that this question does not have clear and unequivocal answers, given that humans have been on the planet for over 200,000 years and so many now claim that we live in a civilized society? In fact, does this not essentially show how uncivilized modern civilization really is? Another way of asking the question is to focus on the requisite needs for the self-actualization of all. In other words, what do humans need to thrive (rather than merely survive)? One widely-used measure of, or proxy for, ‘thriving’ is longevity. Amartya Sen’s seminal article, ‘The Economics of Life and Death’ (1992), succinctly demonstrates the power of this measure. Sen’s metric of long life enables a rather simple, and fairly effective way to measure human success. But, what does Sen conclude is necessary for a long life? Might it be affluence and economic growth?

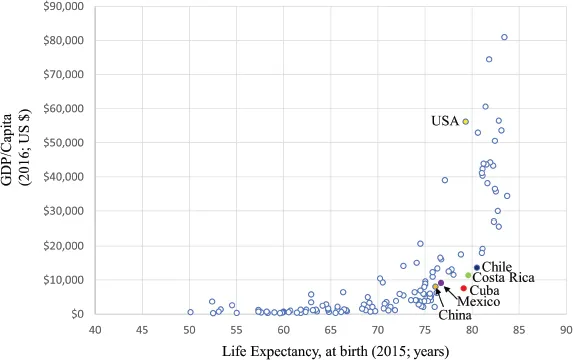

Looking at longevity worldwide, much is revealed. While it is true that most nations that have high life expectancies are among the wealthier ones, there are several important exceptions that seem to suggest that excessive wealth is not necessary for obtaining a long, healthy, and happy life. Our analysis of 129 nations with a population of four million or more (with an average life expectancy of 71.0 years and GDP/capita of US$12,185) reveals that only one country with a life expectancy (LE) of 79.5+ years (i.e., at least one standard deviation above the mean) has a below average GDP per capita: Costa Rica (World Bank, 2015b, 2015c; WHO, 2016); see Fig. 1.1 for visual of this info (notice that Cuba and the U.S. are both just barely below this LE threshold, though Cuba’s GDP per capita is 14% of the U.S.’s). A few of the more populated countries (namely, China, Mexico and Vietnam) have life expectancies of over 76 years despite all having below average GDP per capita values. Note China and Vietnam had socialist economic systems (although private capital is now ascendent), while Costa Rica has eliminated its military. Figure 1.1 also reveals that beyond some level of GDP per capita (~US$10,000), average life expectancy is almost guaranteed to be above 70 years. However, the United States; one of the wealthiest countries in the world, is far from exemplary in terms of longevity. The U.S. also does particularly poorly in the area of infant mortality (Strauss, 2016). All of this is more remarkable when one considers that the U.S. spends far more per capita on healthcare than all other nations, with this disparity being quite substantial when compared to nations such as Japan (the U.S. spends more than twice as much as Japan) which have the longest life expectancies in the World (Brink, 2017). As a result of all this information, we conclude that excessive affluence is not a prerequisite for reaching our ultimate goal. Notice that since the significance of GDP is exaggerated in ‘highly developed’ countries as compared to ‘less developed’ ones because it does not account for (non-paid) volunteer and housework, as well as unsustainable production, this important conclusion is only strengthened. If affluence (as a result of continuous growth of economic systems) is not sufficient or necessary for a healthy global community, what is?

Figure 1.1. GDP/Capita (US $) versus life expectancy (years) (Nations with populations of 4 plus million)

Sources: GDP/Captia → World Bank (2015c); Life Expectancy → WHO (2016).

According to Sen (1992), the keys to living long lives include access to healthcare (particularly, prenatal and infant) and education, gender equality, and food security. In Sen’s analysis, it appears necessary to focus on social and political programs, as it is precisely these that dictate who has/gets health care and food; Sen points out that no democratically-led country has ever endured a famine. Within the US context, focusing on health and education would appear to require an exorbitant expenditure of resources, restricting such reinvestment to the most well-to-do countries. However, such an assumption, which we suspect is deeply imbedded in most contemporary policy makers and bureaucrats in the capitalist world, is ridiculously unfounded. Actually, as Sen (1992) cogently argues, both health and education are labor-intensive enterprises, particularly in the areas that are most important — prenatal, infant, and youth — rather than capital-intensive ones. Also, much of the horrific death of the young from contagious diseases and contaminated water can be eliminated with relatively small expenditures in vaccines, antibiotics, and ceramic water filters. China and Kerala (southwestern state in India, population 35 million in 2012) demonstrate how impactful small, yet strategically invested, contributions can be (Sen, 1992); Cuba, though not explicitly highlighted in Sen (1992), has shown great success in t...