![]()

Chapter 1

Arabic Speech Recognition: Challenges and State of the Art

Sherif Mahdy Abdou1 and Abdullah M. Moussa2

1Faculty of Computers and Information,

Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt

[email protected]

2Faculty of Engineering,

Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt

[email protected] The Arabic language has many features such as the phonology and the syntax that make it an easy language for developing automatic speech recognition systems. Many standard techniques for acoustic and language modeling such as context dependent acoustic models and n-gram language models can be easily applied to Arabic. Some aspects of the Arabic language such as the nearly one-to-one letter-to-phone correspondence make the construction of the pronunciation lexicon even easier than in other languages. The most difficult challenges in developing speech recognition systems for Arabic are the dominance of non-diacritized text material, the several dialects, and the morphological complexity. In this chapter, we review the efforts that have been done to handle the challenges of the Arabic language for developing automatic speech recognition systems. This includes methods for automatic generation for the diacritics of the Arabic text and word pronunciation disambiguation. We also review the used approaches for handling the limited speech and text resources of the different Arabic dialects. Finally, we review the approaches used to deal with the high degree of affixation, derivation that contributes to the explosion of different word forms in Arabic.

1.Introduction

Speech recognition is the ability of a machine or program to identify words and phrases in spoken language and convert them to a machine-readable format. The last decade has witnessed substantial advances in speech recognition technology, which when combined with the increase in computational power and storage capacity, has resulted in a variety of commercial products already on the market.

Arabic language is the largest still living Semitic language in terms of the number of speakers. Around 300 million people use Arabic as their first native language, and it is the fourth most widely used language based on the number of first language speakers.

Many serious efforts have been done to develop Arabic speech recognition systems.1,2,3 Many aspects of Arabic, such as the phonology and the syntax, do not present problems for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR). Standard, language-independent techniques for acoustic and pronunciation modeling, such as context-dependent phones, can easily be applied to model the acoustic-phonetic properties of Arabic. Some aspects of recognizer training are even easier than in other languages, in particular the task of constructing a pronunciation lexicon since there is a nearly one-to-one letter-to-phone correspondence. The most difficult problems in developing high-accuracy speech recognition systems for Arabic are the predominance of non-diacritized text material, the enormous dialectal variety, and the morphological complexity.

In the following sections of this chapter we start by describing the main components of ASR systems and major approaches that have been introduced to develop each of them. Then, we review the previous efforts for developing Arabic ASR systems. Finally, we discuss the major challenges of Arabic ASR and the proposed solutions to overcome them with a summary of state of art systems performance.

2.The Automatic Speech Recognition System Components

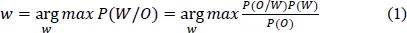

The goal of the ASR system is to find the most probable sequence of words w = (w1, w2,…) belonging to a fixed vocabulary given some set of acoustic observations X = (x1, x2,…, xT). Following the Bayesian approach applied to ASR as shown in Ref. 4, the best estimation for the word sequence can be given by:

To generate an output, the speech recognizer has basically to perform the following operations as shown in Fig. 1:

•Extract acoustic observations (features) out of the spoken utterance.

•Estimate P(W) — the probability of individual word sequence to happen, regardless of the acoustic observations. This is named the language model.

•Estimate P(X/W) — the likelihood that the particular set of features originates from a certain sequence of words. This includes both the acoustic model and the pronunciation lexicon. The latter is perhaps the only language-dependent component of an ASR system.

•Find word sequence that delivers the maximum of (1). This is referred to as the search or decoding.

Fig. 1.The ASR system main architecture.

The two terms P(W) and P(X/W) and the maximization operation constitute the basic ingredients of a speech recognition system. The goal is to determine the best word sequence given a speech input X. Actually, X is not the speech input but a set of features derived from the speech. The Mel Frequency Cepstrum Coefficients (MFCC) and Perceptual Linear Prediction (PLP) are the most widely used. The acoustic and language models and the search operation are discussed below.

2.1.Pronunciation lexicon

The pronunciation lexicon is basically a list where each word in the vocabulary is mapped into a sequence (or multiple sequences) of phonemes. This allows modeling a large number of words using a fixed number of phonemes. Sometimes whole word models are used. In this case the pronunciation lexicon will be a trivial one. The pronunciation lexicon is language-dependent and for a large vocabulary (several thousand words) might require a large effort. We will discuss this for Arabic in the next sections.

2.2.Acoustic model

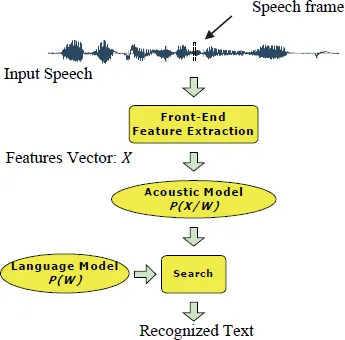

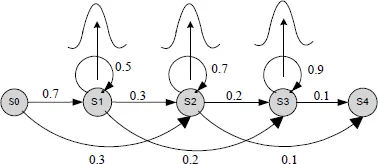

The most popular acoustic models are the so called Hidden Markov Models (HMM). Each phoneme (unit in general) is modeled using an HMM. An HMM4 consists of a set of states, transitions, and output distributions as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.HMM Phone Model.

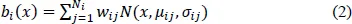

The HMM states are associated with emission probability density functions. These densities are usually given by a mixture of diagonal covariance Gaussians as expressed in equation (2):

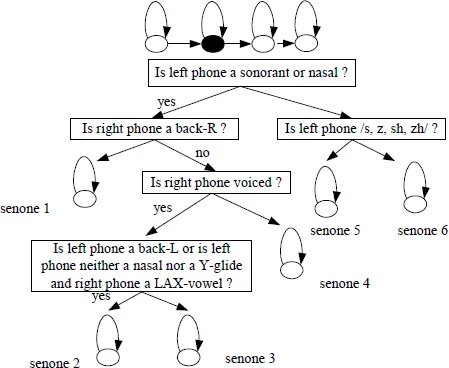

where j ranges over the number of Gaussian densities in the mixture of state Si. The expression N(:) is the value of the chosen component Gaussian density function for feature vector x. The parameters of the model (state transition probabilities and output distribution parameters e.g. means and variances of a Gaussian) are automatically estimated from training data. Usually, using only one model per phone is not accurate enough and usually several models are trained for each phone depending on its context. For example, tri-phone uses a separate model depending on the immediate left and right contexts of a phone. For example, tri-phone A with left context b and right context n (referred to as /b-A-n/) has a different model than tri-phone A with left context t and right context m (referred to as /t-A-m/). For a total number of phones P, there will be P3 tri-phones, and for N states/model, there will be N P3 states in total. The idea can be generalized to larger context e.g. quinphones. This typically leads to a large number of parameters. In practice, context-dependent phones are clustered to reduce the number of parameters. Perhaps the most important aspect in designing a speech recognition system is finding the right number of states for the given amount of training data. Extensive research has been done to address this point. Methods vary from very simple phonetic rules to data driven clustering. Perhaps the most popular technique used is the decision tree clustering.5 In this method, both context questions and a likelihood metric are used to cluster the data for each phonetic state as shown in Fig. 3. The depth of the tree can be used to tradeoff accuracy versus robustness.

Once the context-dependent states are clustered, it remains to assign a probability distribution to each clustered state. Gaussian mixtures are the most popular choice in modern speech recognition systems. The parameters of the Gaussians are estimated to maximize the likelihood of the training data (the so-called maximum likelihood (ML) estimation). For HMMs ML, estimation is achieved by the so-called forward backward or Baum-Welch algorithm.

Fig. 3.Decision tree for classifying the second state of K-triphone HMM.

Although ML remained as the preferred training method for a long time. Recently, discriminative training techniques took over. It was demonstrated that they can lead to superior performance. However, this comes at the expense of a more complex training procedure.6 There are several discriminative training criteria such as Maximum Mutual Information (MMI), Minimum Classification Error (MCE), Minimum - Phone Error (MPE) and most recently Maximum Margin methods. All these different techniques share the idea of using the correct transcription and a set of competing hypotheses. They estimate the model parameters to “discriminate” the correct versus competing hypotheses. The competing hypotheses are usually obtained from a lattice which in turn requires the decoding of the training data. Model estimation is most widely done using the so-called extended Baum-Welch estimation (EBW).7

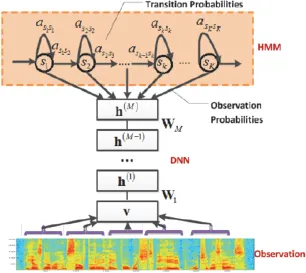

Recently, a better acoustic model was introduced that is a hybrid of HMM and Deep Neural Networks (DNN). The Gaussian Mixtures Models (GMM) are replaced with neural networks with deep number of hidden layers as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.HMM-DNN Model.

The DNNs have a higher modeling capacity per parameter than GMMs and they also have a fairly efficient training procedure that combines unsupervised generative learning for feature discovery with a subsequent stage of supervised learning that fine tunes the features to optimize discrimination. The Context-Dependent (CD)-DNN-HMM hybrid model as shown in Ref. 8 has been successfully applied to large vocabulary speech recognition tasks and can cut word error rate by up to one third on the challenging conversational speech transcription tasks compared to the discriminatively trained conventional CD-GMM-HMM systems.

While the above summarizes how to train models, it remains to discuss the training data. Of course, using more data allows using larger and hence more accurate models leading to better performance. However, data collection and transcription is a tedious and costly process. For this reason, a technique called unsupervised or better lightly supervised training is becoming very popular. First, several hundred hours of speech are used to train a model. The model together with an appropriate confidence measure can then be used to automatically transcribe thousands of hours of data. The new data can then be used to train a larger model. All the above techniques (and more) are implemented in the so-cal...