Chapter 1

Foundation and Growth in New Orleans

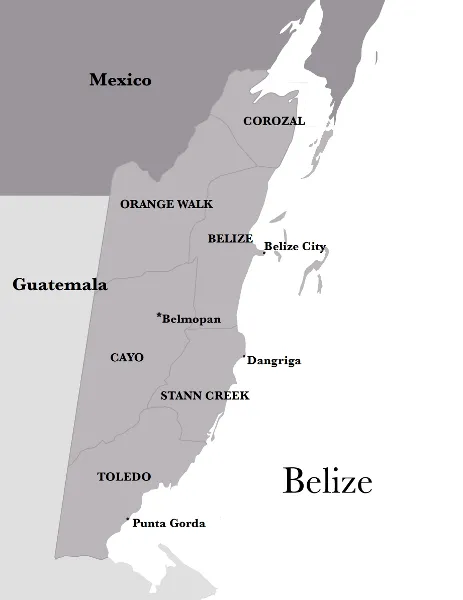

On March 31, 1898, Mother Superior Mary Austin Jones of the Holy Family Sisters, her traveling companion Sister Mary Ann Fazende, the postulant Addie Saffold, and four soon-to-be-missionary sisters boarded a steamer, the Stillwater, at New Orleans.1 The intended destination of the seven African Americans was Stann Creek (today called Dangriga), a settlement on the Atlantic Coast of British Honduras (since 1973 called Belize), south of Belize City. There, the four missionaries—Sisters Mary Rita Mather, Mary Dominica Bee, Mary Emmanuel Thompson, and Mary Stephen Fortier—with the help of Saffold, who would work for a year in the sisters’ preschool program,2 were to run Sacred Heart primary school for mostly black Carib (Garifuna) students,3 whose ancestors had first settled the area in the 1790s.4 An English Jesuit, Brother Daniel Reynolds, had started the school,5 and it was the Jesuit Order that since the 1860s had labored virtually alone in evangelizing the Caribs,6 a close-knit people descended from shipwrecked African slaves and indigenous Caribbean islanders.

After an uneventful voyage, the steamer docked at Belize City on April 3, where the seven religious women stayed overnight with the Sisters of Mercy, a white congregation, who, like the Holy Family Sisters, were also from New Orleans. The Mercy nuns were the second Catholic religious order to enter British Honduras and had been teaching at St. Catherine’s and Holy Redeemer primary schools since 1883. In 1886 they had opened St. Catherine’s Academy, the oldest Catholic secondary school in Belize.7 The next morning, after a “hearty breakfast” provided by the Mercy community, the Holy Family nuns were given a tour of St. Catherine’s convent and “select school.”8 At about 3:00 p.m., the seven companions reboarded the Stillwater, which had finally finished unloading the bulk of its cargo. After sailing south for an additional thirty-six miles, the nuns reached their destination.

Because Stann Creek had no wharf, but only a pier for small craft, all seven religious had to be lowered from the ship into a rowboat (called a “dorey” by the natives) about a mile offshore. Since they were dressed in their bulky habits, this transfer was not only a frightening experience but also an adventure that became part of the congregation’s folklore. When they reached the pier, Jesuit Fathers C. J. Leibe and Matharus Antillach greeted them, as did a large contingent of townspeople. After a most impressive welcome, they were shown to their convent, a small frame building with a zinc roof, prepared for them by the Jesuits and the families of the merchants of the town, “who left nothing undone to make everything as comfortable as possible.”9 On April 12 the sisters took charge of Sacred Heart, which by British Honduran law served as a public school. They also opened a select school for students who could afford to pay tuition.10

On April 15, after making sure that all was in order, Mother Austin returned to New Orleans with her traveling companion. Sister Mary Francis Borgia Hart, in her in-house history of the Holy Family community, sums up the mother superior’s impressions of her first trip to British Honduras: “The primitive condition of the people, the unique reception given to the Sisters and the nature of the work which was to be done for God’s glory, so impressed the Mother, that Stann Creek and the Caribs won a place in her zealous heart, and until her death, its needs and the frequent replacements of its personnel claimed her attention, and were always the first to be served.”11 Perhaps Mother Austin realized that the mission begun by the four sisters whom she had left behind was a historic first, in that it was the earliest missionary endeavor by Catholic African Americans, male or female.12 From extant sources, however, it is clear that she and her sisters were well aware of the hurdles they would face. Consequently, using pragmatic mechanisms they had developed in their struggle to survive in nineteenth-century New Orleans, they would overcome racial and gender discrimination and in some ways would even turn these negatives to their advantage. As a result, the congregation would enjoy over a century of remarkable missionary success.

Before addressing the Holy Family Sisters’ ministry in Belize, however, it should prove useful to look at the unique origin and early history of this congregation. This, in turn, necessitates a review of Henriette Delille, the foundress of the religious community, and the peculiar environment from which she came.

Henriette was born in New Orleans in 1812. Although we are not completely sure who her father was, it is virtually certain that he was a member of the Creole class, that is, he was a white gentleman probably of French or Spanish descent. Her mother, Marie Josephe Dias, was a Creole femme de couleur libre (free woman of color) whose parentage was of mixed race, on the paternal side Caucasian and on the maternal a mixture of African and white. Just like Henriette, her mother was the offspring of a white Creole and a femme de couleur libre. Her maternal grandmother, Henriette Leveau, and great-grandmother, Cecile Dubreuil, although born into slavery and later freed, were likewise of mixed race, but her great-great-grandmother, Nanette, was an African slave.13 Thus, for three generations her ancestors had an arrangement known as plaçage (placing). They did not marry—interracial marriages were illegal—but instead voluntarily entered into a liaison whereby the femme de couleur libre was kept by her Creole lover as his mistress. Herbert Asbury, in his racy The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld, claims that it was indeed rare for a young Creole gentleman not to have a femme de couleur libre as his paramour.14 Sometimes these relationships remained for life but this was uncommon. Almost always the male partners in these arrangements “came and went … leaving the women to raise their children with little or no support.”15

Young free women of color usually received a practical education while also being schooled by their mothers in the ways of seduction. When they were old enough, they would be elaborately dressed and escorted by their mothers to so-called quadroon balls to be paraded before young white male suitors. A gentleman who fancied one of the girls would then reach an understanding with her mother. When the plaçage was finalized, she was usually set up in a small apartment. After 1832, the most famous and ornate quadroon balls were held every Tuesday and Friday night at the Orleans Ballroom. Quadroon balls began to decline in popularity about 1850 and by the end of the Civil War had virtually ceased to exist. It is no coincidence that in 1881 the Holy Family Sisters purchased the Orleans Ballroom and transformed it into a convent and school for black girls.16

This, then, was the peculiar society into which Henriette Delille was born. She was the youngest of four children, one of whom died while still an infant. While the different fathers of her surviving sister and brother have been identified, the name of hers is not certain, although it seems most probable that he was Jean-Baptiste Delille. What does seem clear, however, is that he took little if any interest in his daughter.17 Moreover, since Henriette’s older sister, Cecile Bonille, contracted into a plaçage in 1824, it is virtually certain that the same fate was planned for her.18

That this was not to be was in part due to Sister Marthe Fontière, a French Dame Hospitalière who opened a school for free girls of color in New Orleans in 1823. According to oral tradition passed down by the Holy Family Sisters, it seems that Fontière allowed some students, including Henriette and her close friend, Juliette Gaudin, to assist her in her ministry, which included teaching catechism to children and to adult female slaves. Fontière and her work so impressed her two teenage helpers that they resolved to dedicate themselves to a life of religious service.19

For the next few years, Henriette and Juliette continued their ministry to the poor while holding firm to their desire for the religious life. In 1836 they were two of a small group of free women of color to join Marie Jeanne Aliquot in forming a religious confraternity dedicated to serving poor blacks. But soon Aliquot, who was white, left the group, possibly due to Louisiana racial laws. Most of the other members, discouraged by the hardships and prejudice they encountered, eventually followed her lead. The remnant—Delille, Gaudin, and a few other femmes de couleur libre—struggled on. On November 21, 1836, they organized themselves under the name of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and drew up “Rules and Regulations” for their confraternity, committing the “sisters” to a common purpose: “to care for the sick, help the poor and instruct the ignorant.”20 It is evident from the details of the “Rules and Regulations” that the “Sisters of the Presentation” were no more than a pious association of laywomen. Nevertheless, the fact that they chose to call themselves “sisters” indicates that their goal was to eventually transform themselves into a traditional community of vowed religious.

In 1842 the small band of femmes de couleur libre moved closer toward this goal when Père Etienne Rousselon, the diocesan vicar general and the women’s spiritual director-chaplain, leased a group home for them near St. Augustine Church, where he was pastor. Delille, Gaudin, and a third member, Josephine Charles, who up to this time had been residing at home with their families, could now live together in community. The women had not been permitted by the archbishop to take formal vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, however, nor had they gone through a novitiate program. Thus, they were not recognized as a vowed religious congregation, but rather, according to the official diocesan directory, as a “pious association for the relief of the indigent and sick.”21 Rousselon named Delille head of the new community and, following his suggestion, the women changed their name from the Sisters of the Presentation to the Sisters of the Holy Family.

In 1847, Henriette and her companions, along with several of their financial supporters, incorporated themselves with the state of Louisiana as the Society of the Holy Family. This move was important because it gave “the sisters” a legal basis for their ministry. In 1850, using her inheritance and money borrowed from Marie Jeanne Aliquot, Delille purchased a residence for her community on Bayou Road.22 The building was spacious enough to allow the “sisters” to open a school for femmes de couleur libre.

By this time the Society of the Holy Family was providing an invaluable service to the Archdiocese of New Orleans through its ministry to black slaves and free people of color. Archbishop Antoine Blanc was fully aware of these efforts and as a result seems to have been willing to help the pious women fulfill their dream of becoming a vowed religious community. This had to be done with great discretion, however, due to the laws and social mores of the time. Thus, there is little extant evidence to help us understand exactly how and when Delille and her companions became a diocesan-approved congregation of sisters. According to the oral tradition of the Holy Family Sisters, Père Rousselon convinced the Religious of the Sacred Heart at St. Michael’s Convent in Convent, Louisiana, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, to allow Delille to make her novitiate year with them in 1850. Upon her return to Bayou Road, she then served as novice mistress for her Holy Family companions.

Although there is conclusive evidence that Delille spent time living with the Religious of the Sacred Heart, there is no documentation that she did so to fulfill the novitiate requirement so that her community could become vowed religious.23 Nevertheless, as Cyprian Davis notes, although we do not know all the particulars of Delille’s stay at St. Michael’s Convent, “there is little doubt that somehow Henriette and her companions received enough formation to satisfy the archdiocese that they might make religious vows,” and very likely they did so in 1851 or 1852.24 However, as Davis points out, those vows must have been taken privately, since Delille is not listed during her lifetime as a “sister” in any official church document.25 Indeed, this fact has led historian Tracy Fessenden to question whether Delille was ever actually considered a vowed religious sister by the institutional church of her time.26 At any rate, under civil law the three women were definitely not recognized as “sisters” since they were non-Caucasian.27 We do know that at this time they began to wear a simple black cotton dress and black bonnet as their uniform. It was not until 1876, however, that they were finally allowed by the archbishop to wear an official religious habit publicly;28 and it was not until March 19, 1887, that the archbishop of New Orleans finally approved the formal rule of the congregation.29

Sister Borgia Hart tells us that in the early years the sisters’ “presence on the streets [of New Orleans] was hailed with ridicule; for, in the minds of the early inhabitants … Colored Sisters were simply an anomaly.”30 Nevertheless, they persevered; and during the yellow fever epidemic of 1853, they so courageously nursed the sick that they earned some credibility and respect.31

Throughout the antebellum period, the small group of sisters struggled for survival. Occasionally a woman would join the three co-founders, but the congregation’s tenuous situation and the long hours of arduous work expected of its members in service to the poor took their toll, and the woman usually left the community. By the end of the Civil War there were only five Sisters of the Holy Family. And indeed, during the war, spent by years of backbreaking toil and anxieties, Mother Henriette died on November 16, 1862. Her obituary, which appeared on the first page of the archdiocesan newspaper, Le Propagateur, is revealing:

Last Monday there died one of those women whose obscure and retired life has nothing remarkable in the eyes of the world but is full of merit before God. Miss Henriette Delille had for long years devoted herself without reserve to the instruction of the ignorant … and principally of the slaves. To perpetuate this sort of apostolate so difficult yet so necessary she had founded with the help of certain pious persons, the House of the Holy Family, a house poor and little known except by the poor and the young and, which for the past ten or twelve years, has produced, without fanfare, a considerable good which will continue…. Worn out by work, she died at the age of fifty years after a long and painful illness borne with most edifying resignation. The crowd gathered for her funeral testified by its sorrow how keenly felt was the loss of her who for the love of Jesus Christ had made herself the humble and devoted servant of the slaves.32

The fact that Mother Henriette’s obituary appeared on page 1 testifies to her importance within the Catholic community of New Orleans. The large crowd reported to have attended her funeral mass likewise is a testament to the success of her congregation’s much-needed apostolate to the poorest of the poor, the black slave.

At the same time, one cannot help but notice that in the obituary Henriette is referred to as “Miss” and never as “Mother” or “Sister,” and her congregation is called the “House of the Holy Family” rather than the “Sisters of the Holy Family.” The avoidance of titles that would designate Henriette and her associates as “real religious” is testimony to the racial prejudice that the Holy Family Sisters had to face not only at that time ...