![]()

IV

Elementary Studies

It has often been observed that, when the eyes of the infant first open upon the world, the reflected rays of light which strike them from the myriad of surrounding objects present to him no image, but a medley of colours and shadows. They do not form into a whole; they do not rise into foregrounds and melt into distances; they do not divide into groups; they do not coalesce into unities; they do not combine into persons; but each particular hue and tint stands by itself, wedged in amid a thousand others upon the vast and flat mosaic, having no intelligence, and conveying no story, any more than the wrong side of some rich tapestry. The little babe stretches out his arms and fingers, as if to grasp or to fathom the many-coloured vision; and thus he gradually learns the connexion of part with part, separates what moves from what is stationary, watches the coming and going of figures, masters the idea of shape and of perspective, calls in the information conveyed through the other senses to assist him in his mental process, and thus gradually converts a calidoscope into a picture. The first view was the more splendid, the second the more real; the former more poetical, the latter more philosophical. Alas! what are we doing all through life, both as a necessity and as a duty, but unlearning the world’s poetry, and attaining to its prose! This is our education, as boys and as men, in the action of life, and in the closet or library; in our affections, in our aims, in our hopes, and in our memories. And in like manner it is the education of our intellect; I say, that one main portion of intellectual education, of the labours of both school and university, is to remove the original dimness of the mind’s eye; to strengthen and perfect its vision; to enable it to look out into the world right forward, steadily and truly; to give the mind clearness, accuracy, precision; to enable it to use words aright, to understand what it says, to conceive justly what it thinks about, to abstract, compare, analyze, divide, define, and reason, correctly. There is a particular science which takes these matters in hand, and it is called logic; but it is not by logic, certainly not by logic alone, that the faculty I speak of is acquired. The infant does not learn to spell and read the hues upon his retina by any scientific rule; nor does the student learn accuracy of thought by any manual or treatise. The instruction given him, of whatever kind, if it be really instruction, is mainly, or at least pre-eminently, this,—a discipline in accuracy of mind.

Boys are always more or less inaccurate, and too many, or rather the majority, remain boys all their lives. When, for instance, I hear speakers at public meetings declaiming about “large and enlightened views,” or about “freedom of conscience,” or about “the Gospel,” or any other popular subject of the day, I am far from denying that some among them know what they are talking about; but it would be satisfactory, in a particular case, to be sure of the fact; for it seems to me that those household words may stand in a man’s mind for a something or other, very glorious indeed, but very misty, pretty much like the idea of “civilization” which floats before the mental vision of a Turk,—that is, if, when he interrupts his smoking to utter the word, he condescends to reflect whether it has any meaning at all. Again, a critic in a periodical dashes off, perhaps, his praises of a new work, as “talented, original, replete with intense interest, irresistible in argument, and, in the best sense of the word, a very readable book;”—can we really believe that he cares to attach any definite sense to the words of which he is so lavish? nay, that, if he had a habit of attaching sense to them, he could ever bring himself to so prodigal and wholesale an expenditure of them?

To a short-sighted person, colours run together and intermix, outlines disappear, blues and red and yellows become russets or browns, the lamps or candles of an illumination spread into an unmeaning glare, or dissolve into a milky way. He takes up an eye-glass, and the mist clears up; every image stands out distinct, and the rays of light fall back upon their centres. It is this haziness of intellectual vision which is the malady of all classes of men by nature, of those who read and write and compose, quite as well as of those who cannot,—of all who have not had a really good education. Those who cannot either read or write may, nevertheless, be in the number of those who have remedied and got rid of it; those who can, are too often still under its power. It is an acquisition quite separate from miscellaneous information, or knowledge of books. This is a large subject, which might be pursued at great length, and of which here I shall but attempt one or two illustrations.

§ 1 Grammar

1

One of the subjects especially interesting to all persons who, from any point of view, as officials or as students, are regarding a University course, is that of the Entrance Examination. Now a principal subject introduced into this examination will be “the elements of Latin and Greek Grammar.” “Grammar” in the middle ages was often used as almost synonymous with “literature,” and a Grammarian was a “Professor literarum.” This is the sense of the word in which a youth of an inaccurate mind delights. He rejoices to profess all the classics, and to learn none of them. On the other hand, by “Grammar” is now more commonly meant, as Johnson defines it, “the art of using words properly,” and it “comprises four parts—Orthography, Etymology, Syntax, and Prosody.” Grammar, in this sense, is the scientific analysis of language, and to be conversant with it, as regards a particular language, is to be able to understand the meaning and force of that language when thrown into sentences and paragraphs.

Thus the word is used when the “elements of Latin and Greek Grammar” are spoken of as subjects of our Entrance Examination; not, that is, the elements of Latin and Greek literature, as if a youth were intended to have a smattering of the classical writers in general, and were to be able to give an opinion about the eloquence of Demosthenes and Cicero, the value of Livy, or the existence of Homer; or need have read half a dozen Greek and Latin authors, and portions of a dozen others:—though of course it would be much to his credit if he had done so; only, such proficiency is not to be expected, and cannot be required, of him:—but we mean the structure and characteristics of the Latin and Greek languages, or an examination of his scholarship. That is, an examination in order to ascertain whether he knows Etymology and Syntax, the two principal departments of the science of language,—whether he understands how the separate portions of a sentence hang together, how they form a whole, how each has its own place in the government of it, what are the peculiarities of construction or the idiomatic expressions in it proper to the language in which it is written, what is the precise meaning of its terms, and what the history of their formation.

All this will be best arrived at by trying how far he can frame a possible, or analyze a given sentence. To translate an English sentence into Latin is to frame a sentence, and is the best test whether or not a student knows the difference of Latin from English construction; to construe and parse is to analyze a sentence, and is an evidence of the easier attainment of knowing what Latin construction is in itself. And this is the sense of the word “Grammar” which our inaccurate student detests, and this is the sense of the word which every sensible tutor will maintain. His maxim is, “a little, but well;” that is, really know what you say you know: know what you know and what you do not know; get one thing well before you go on to a second; try to ascertain what your words mean; when you read a sentence, picture it before your mind as a whole, take in the truth or information contained in it, express it in your own words, and, if it be important, commit it to the faithful memory. Again, compare one idea with another; adjust truths and facts; form them into one whole, or notice the obstacles which occur in doing so. This is the way to make progress; this is the way to arrive at results; not to swallow knowledge, but (according to the figure sometimes used) to masticate and digest it.

2

To illustrate what I mean, I proceed to take an instance. I will draw the sketch of a candidate for entrance, deficient to a great extent. I shall put him below par, and not such as it is likely that a respectable school would turn out, with a view of clearly bringing before the reader, by the contrast, what a student ought not to be, or what is meant by inaccuracy. And, in order to simplify the case to the utmost, I shall take, as he will perceive as I proceed, one single word as a sort of text, and show how that one word, even by itself, affords matter for a sufficient examination of a youth in grammar, history, and geography. I set off thus:—

Tutor. Mr. Brown, I believe? sit down. Candidate. Yes.

T. What are the Latin and Greek books you propose to be examined in? C. Homer, Lucian, Demosthenes, Xenophon, Virgil, Horace, Statius, Juvenal, Cicero, Analecta, and Matthiæ.

T. No; I mean what are the books I am to examine you in? C. is silent.

T. The two books, one Latin and one Greek: don’t flurry yourself. C. Oh, … Xenophon and Virgil.

T. Xenophon and Virgil. Very well; what part of Xenophon? C. is silent.

T. What work of Xenophon? C. Xenophon.

T. Xenophon wrote many works. Do you know the names of any of them? C. I … Xenophon … Xenophon.

T. Is it the Anabasis you take up? C. (with surprise) O yes; the Anabasis.

T. Well, Xenophon’s Anabasis; now what is the meaning of the word anabasis? C. is silent.

T. You know very well; take your time, and don’t be alarmed. Anabasis means … C. An ascent.

T. Very right; it means an ascent. Now how comes it to mean an ascent? What is it derived from? C. It comes from … (a pause). Anabasis … it is the nominative.

T. Quite right: but what part of speech is it? C. A noun,—a noun substantive.

T. Very well; a noun substantive; now what is the verb that anabasis is derived from? C. is silent.

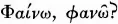

T. From the verb

, isn’t it? from

.

C. Yes.

T. Just so. Now, what does

mean?

C. To go up, to ascend.

T. Very well; and which part of the word means

to go, and which part

up? C.

is

up, and

is

go.

T.

to go, yes; now

What does

mean?

C. A going.

T. That is right; and

C. A going up.

T. Now what is a going down? C. is silent.

T. What is down? …

… don’t you recollect?

.

C.

.

T. Well, then, what is a going down? Cat … cat … C. Cat….

T. Cata … C. Cata….

T. Catabasis. C. Oh, of course, catabasis.

T. Now tell me what is the future of

C. (

thinks)

.

T. No, no; think again; you know better than that.

C. (

objects)

T. Certainly,

is the future of

but

is, you know, an irregular verb.

C. Oh, I recollect,

.

T. Well, that is much better; but you are not quite right yet;

.

C. Oh, of Course,

.

T.

. Now do you mean to say that

comes from C. is silent.

T. For instance:

comes from

by a change of letters; does

in any similar way come from

C. It is an ir...