![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE RULES

Formal and Informal

Leaders of newly independent nations throughout the Americas in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries faced the challenge of determining what type of governing system best suited their societies. Regardless of the examples of the United States’ break from Great Britain and of Spain’s former colonies, national leaders in what came to called Latin America tended to equate independence with liberalism and modernism, but feared the extension of liberty to the masses of society. Hence, they often ended up living in complex, paradoxical systems, hybrid societies of sorts. They touted the merits of equality and structured their societies as republics in which popular elections determined officeholding, and yet they operated under a different set of informal rules that constrained freedom and concentrated authority. El Salvador was one of these new nations, and its tendency to fall into this pattern resembled that of its neighbors.

This chapter looks at the formal and informal rules that governed political life in El Salvador. The formal rules were officially laid down in constitutions and ordinances, and they explained how elections were supposed to work and how politics was expected to transpire. The informal rules were the ways in which people actually behaved when they did politics and conducted elections. The informal rules tended to stick to the letter of the formal rules; after all, people voted, and political leaders took office only after having won an election. But the informal rules diverged substantially from the spirit of the law. If the basic premise behind the concepts of popular will and freedom of suffrage was that individual voters had the right to select their leaders from a range of options without duress or coercion, then democracy was fleeting throughout the first century of El Salvador’s existence.

The following vignette from the vice presidential election of 1895 is presented as a metaphor for the broader whole of politics and elections in El Salvador. Most of the remaining evidence in this chapter will be drawn from the nineteenth century in order to set up the next chapter’s series of chronologically ordered case studies.

The Vice Presidential Election of 1895

The vice presidential election of 1895 left behind some of the most detailed records of any election in El Salvador. The records consist of municipality-by-municipality voting results, as well as a slew of telegrams and reports exchanged between the municipal and national levels, including some rare communiques between candidates and their local electoral activists. This cache of evidence reveals how national-level patronage networks and the accompanying electoral system functioned at a particular moment in time.

The 1895 vice presidential election occurred in the wake of a coup d’état led by General Rafael Gutiérrez (1894–1899) that overthrew President Carlos Ezeta (1890–1894). In the subsequent presidential election, Gutiérrez ran unopposed and won by a margin of 61,080 votes to 91—in other words, by the typically unanimous or near-unanimous result of an unrivaled political boss.1 However, Gutiérrez had below him two powerful allies, Prudencio Alfaro and Carlos Meléndez—the latter would go on to hold the presidency in 1913. In the meantime, both Alfaro and Meléndez had played lead roles in Ezeta’s overthrow, but only one of them could become vice president. Gutiérrez apparently decided not to choose between his two aspiring underlings and instead allowed them to battle it out in an election. Alfaro won the contest with 38,006 votes to Meléndez’s 18,792, with the remaining 4,000 votes being divided up between four lesser candidates.

Those results make it appear that the election was genuinely competitive, and indeed at some level it was. Candidates faced off, voters from across the country cast votes, those votes were tallied up, and a winner was declared. But more revealing than the final result is the manner in which voting was conducted at the municipal level. Records reveal that voting within each municipality was not very competitive; in most cases it was decided by unanimous or near-unanimous results, and patronage networks were clearly in operation. The election was built around the practice of each candidate contacting powerful allies in the department capitals who in turn called upon subordinate political bosses in the municipalities. The municipal bosses were expected to control the polls in their towns and prevent affiliates of the rival candidates from doing the same. A close election such as this one, between two powerful political players such as Alfaro and Meléndez, would normally have ended in bloodshed, just as the rivalry between Generals Gutiérrez and Ezeta had. Fortunately, in this case, the presence of an undisputed superior authority, General Gutiérrez, ensured a peaceful process.

Alfaro’s point man in Sonsonate Department was Abrahán Rivera, a prominent landowner and a rising political boss in Sonsonate City.2 In the following letter, Rivera informs Alfaro of his success in Sonsonate Department on election day.

Dr. don Prudencio Alfaro

My dear friend:

As we expected, in this department, with the exception of Izalco and Armenia, where there was imposition of comandantes working on behalf of other candidates, our triumph has been complete: The great majority has voted in our favor. In Nahuizalco, which is the toughest municipality in terms of elections, we have won with almost unanimity. At the last minute they had changed the comandante with the intention of altering the voting in favor of Pérez, but in the end this comandante could do nothing on account of the efficient work of Colonels Marcelo Brito and Lucas Peñate and of don Abrahán Guerra who have carried the day like true champions. In Juayúa, which is another important village, our triumph is complete. Colonel Tadeo Pérez [no relation to candidate Pérez] took the baton and aided us with great fortitude. In San Julián and the other coastal villages we have triumphed splendidly due to the cooperation of don Dionisio Herrera and the Señores Chinchilla and de León. In all the municipalities surrounding this city [Sonsonate] I have had very good agents at work, such that you won almost by unanimity. In this population where there has been the most work of the Melendistas, I have put a close watch on these rabbits [conejos] . . . so that despite the great amount of work that was being done on behalf of Meléndez, we reduced their supporters to an insignificant number.

Abrahán Rivera, Sonsonate, January 16, 18953

Rivera’s letter offers a rare and vivid description of a patronage-based political network in action. In his letter, Rivera lists each local subaltern by name and describes how they neutralized the local affiliates of the rival candidates. As Rivera points out, his allies reigned supreme in all but two of the department’s fourteen municipalities. Final returns from the election confirm his claim. Excluding those two outliers, Izalco and Armenia, Alfaro won the department by a combined total of 2,565 votes to 65.4

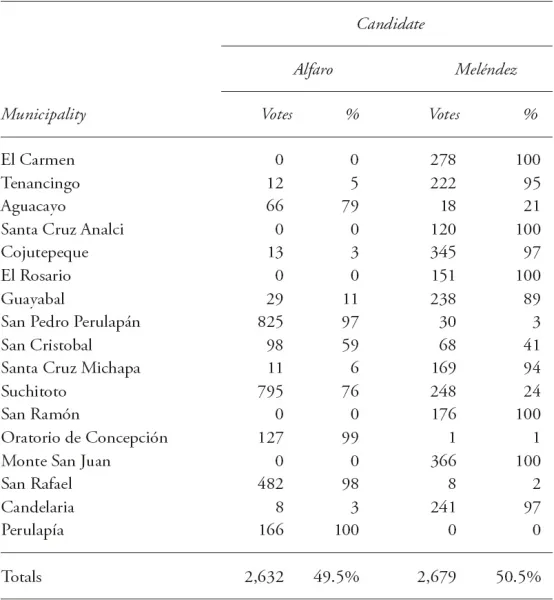

Complete returns from the 1895 election provide a nationwide view of the monopolization of polling stations and demonstrate that what transpired in Sonsonate was typical. Voting occurred in all 248 municipalities in the nation. In 176 of these municipalities the victorious candidate won with more than 95 percent of the vote, including 96 municipalities where voting was unanimous. Alfaro’s network dominated seven of the fourteen departments (La Paz, Usulután, San Miguel, La Unión, Morazán, Ahuachapán, and Sonsonate), winning them by a combined total of 20,320 to 2,574. To his detriment, Meléndez controlled only two departments by comparable margins, San Vicente and Cabañas: 4,931 votes to 600. In the remaining five departments (Cuscatlán, Chalatenango, Santa Ana, San Salvador, and La Libertad) the two candidates split the departmentwide vote evenly, but voting at the municipal level was starkly divided. Cuscatlán Department provides a clear example. Alfaro and Meléndez each took 50 percent of the vote, but in thirteen of the department’s seventeen municipalities the victorious candidate won with more than 94 percent of the votes, including six municipalities that were decided by unanimity (see table 1.1). A similar result is found in Chalatenango Department, where Alfaro received just over 4,000 votes and Meléndez just under 3,000, a relatively even split. In twenty-seven of Chalatenango’s thirty-five municipalities victory was attained with at least 91 percent of the votes. Unfortunately, the historical record does not contain detailed letters from affiliates in other departments comparable to Rivera’s correspondence from Sonsonate. It can be safely assumed that in each of those departments, men like Rivera were diligently working on the behalf of Alfaro or Meléndez in the same way that Rivera was doing in Sonsonate. When Alfaro assumed the office of vice president, he knew that he owed those departmental bosses something for their support, or that he had burned through some of the political capital that he had accrued previously.

Table 1.1 Voting in Cuscatlán Department, Vice Presidential Election, 1895

Source: Asamblea Nacional, “Elección de 1895,” AGN, MG, unclassified box.

In those departments where voting was divided evenly, neither candidate’s network achieved departmentwide supremacy; there were no equivalents to Sonsonate’s Abrahán Rivera. Instead the candidates settled for as many municipalities as their subordinates could muster. In a recurrent scene, one municipality provided near-unanimous support for one candidate, while a neighboring municipality, sometimes located just a few kilometers down the road, produced an equally complete victory for a rival candidate. Overall, the results of the 1895 election highlight the golden rule of politics in El Salvador: to win an election, a network had to monopolize voting.

The 1895 election also reveals the democracy-laden discourse that accompanied these nondemocratic procedures. Carlos Meléndez was supported in his electoral bid by the newspaper La Verdad, based in the city of Nueva San Salvador. Unfortunately, no copies of that newspaper are known to have survived. But we know something of the claims made in La Verdad because after the election, Alfaro’s supporters responded to them in a pair of lengthy editorials in the government’s official newspaper, Diario Oficial. It seems that Meléndez did not take his defeat in stride. Although he had supported General Gutiérrez during the 1894 coup, he broke with him after his failed bid to become vice president. Shortly after the election, Meléndez’s supporters (and probably Meléndez himself), launched a vigorous public relations campaign in the pages of La Verdad, claiming that the past elections for both president and vice president had been done fraudulently and against popular will. In the words of the Diario Oficial editorialists, La Verdad claimed that “there had been no liberty in the elections,” the “victorious candidates for the executive offices had been imposed,” and thus the “new government was illegal.”5

Gutiérrez’s supporters in Diario Oficial responded to those claims in multiple ways. First, they dismissed La Verdad on ideological grounds, accusing it of being “a clerical, Catholic newspaper” opposed to liberalism. Then they discredited the claims of electoral imposition in the vice presidential election by showing the departmentwide results that they touted as proof that multiple candidates received votes.

In the San Salvador Department Alfaro received 4,543 votes; Meléndez received 2,696.

Santa Ana. – Pérez 1,901. Alfaro, 1,210. Regalado, 432.

La Libertad. – Meléndez, 2,752. – Alfaro 1,001. Regalado, 472.

Sonsonate. – Alfaro 3,645 – Pérez. 590 – Meléndez, 188 – Hurtado, 177.

San Vicente. – Meléndez, 3,170 – Alfaro, 260.

Ahuachapán. – Alfaro, 2,635 – Meléndez, 2,634.

La Paz. – Alfaro, 3,334 – Meléndez, 408.

Usulután. – Alfaro, 3,096 – Meléndez, 270.

Chalatenango. – Alfaro, 4,278 – Meléndez, 2,750.

Armed with that evidence, the authors insisted that “only a losing candidate blinded by party loyalty” could fail to see “that the numerical results prove that an imposition under such circumstances was impossible.” Thus, they summarized, “the election for the vice president . . . has been free.”6

Defending the presidential election was more of a challenge because, after all, Gutiérrez had been elected by unanimity without an opponent. The authors in Diario Oficial explained that “the unanimity is the result of the prestige of the April [1894] Revolution, the respect its leaders have shown for public liberty, and the honor demonstrated by the Provisional Government.” Thus, the authors concluded that the executive officers’ right to govern had been established by “the Salvadoran people freely exercising their right to vote in the most recent elections.”7

In many and diverse ways, the vice presidential election of 1895 symbolizes the nature of electoral politics in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century El Salvador. First and foremost, it reveals that a lot of people voted in elections. Assuming that widespread ballot stuffing did not swell the numbers of voters, the more than sixty thousand votes cast represented at least 40 percent of eligible voters.8 That is a lot of people physically making their way to a polling station on election day, especially considering that a sizeable portion of those people who did not vote were probably supporters of the recently ousted Ezeta network and thus would not have been allowed to vote. If nothing else, the high turnout indicates that political leaders took elections seriously. However predetermined the outcome may have been, as in the case of Gutiérrez’s presidential election, or however managed the voting was at any given polling station, such as during the vice presidential contest between Alfaro and Meléndez, political leaders needed their rule sanctified by an election, and they wanted people showing up on election day to legitimize the process.

Another characteristic revealed by this election is the absence of political platforms, policy proposals, or ideological vision. The candidates made no apparent attempt to explain themselves to voters or appeal to their particular interests—or, at least, no evidence survives to indicate that they did. Instead, the election consisted simply of two powerful national-level political actors lining up allies in municipalities to control voting at polling stations. Whatever means national political bosses employed to build alliances at the local level, and however local political bosses constructed their networks in the municipalities, be it coercion, persuasion, or both, they put them to work on election day by getting voters to the polls in support of the national-level boss.

The fact that voting occurred in the municipalities, under the purview of municipal authorities, provided the raw material for building the complex webs of patronage that bound local, regional, and national actors together. In fact, the electoral machinery used in national elections, such as voter registration lists (examined in more detail below), had been in action just a few weeks prior in municipal elections. Thus, the ability to deliver votes for a national-level politician was a direct continuation of delivering the same for oneself or one’s allies in a recent municipal election.

The success of national-level candidates hinged upon the capabilities of worthy and dutiful allies at the departmental and municipal levels, men like Abrahán Rivera in Sonsonate City. It is not clear what Rivera received from Alfaro for his successful efforts in Sonsonate. Perhaps Rivera was repaying a debt to Alfaro. Perhaps he received a government position in San Salvador. Perhaps he simply accrued political capital for his own battles in Sonsonate—assurance that a future petition from him would receive a favorable review at the national level. The available evidence does not reveal enough about Rivera’s career to say for certain, but unless he was somehow exceptional, he is likely to have applied one or another of these options.

Finally, the vice presidential election of 1895 shows that a rhetoric of democracy accompanied elections. Both Meléndez and Alfaro appealed to the principles of popular will, free suffrage, and democratic liberty to justify their assessments of the election. No one disparaged democracy. Rather, they accused...