![]() THE PATHS OF TIME

THE PATHS OF TIME![]()

LOOKS

My memory opens up, painfully, at the sound of persistent calls. I am emerging from the long tunnel where I have lain low.

Thousands of faces disappeared

Without knowing why. They call out to me

They are full of distress

Humiliation

Blazing with hunger

Snuffed out by thirst.

The tense look of a friend whose flesh bore the marks of a dog’s bite

With each step she was losing her life.

The overwhelmed look of another woman beaten to death.

Hundreds of fading looks, exhausted from long hours of roll calls.

On thousands of lost faces, the dejection of a life terminated too soon.

Trucks come and go down their long lanes of despair

Filled with lives, packed tight, their eyes looking into the distance.

Holding out their emaciated hands, clinging onto life with wasted screams.

The smokestack crackles.

The sky is low, gray and yellow.

We breathe in their ashes as the wind blows them away.

Thirty years later

I tremble as I push through the thick wall of my memory.

So that all those looks begging for hope

Do not vanish

Into the dust.

![]()

DEPARTURE

I remember a journey of three days cooped up in a cattle wagon. For Mom, my sister, and me, it was the last journey we made together. Just like birds hiding their heads beneath their wings when threatened, I sensed danger with my eyes shut.

With a massive jolt and the piercing screech of a whistle, the wagon doors opened onto thick fog and an icy yellow light. All of a sudden I was plunged into a sea of dogs and men barking. “Hurry up! Los, schnell!” “How old are you? To the right!” “Your mother? To the left!” “Your sister? To the left!”

I blindly made my way to the right and within minutes death had visited the left.

Very quickly a different me was born, one that great black beasts with fangs would hustle toward a fragile fate.

The air smelled of burnt flesh. The paths were littered with sharp stones. Feet dragged ahead and behind me. The convoy came to a halt. I looked up and saw a group of huts. Without realizing it I was already sitting on straw. We stared at each other in silence, not really sure if it was a man or a woman in front of us. Looking into the dilated pupils of the women around me I realized how shocked I was to be sitting opposite a stranger. What are you doing here? Can this be real? Unbelievable!

This was already everyday life in Auschwitz.1

![]()

ONE DAY

A whistle screeched. We were chased off our wooden planks in a brawl of elbows, whips, and shouts. Hustled toward the steaming flasks, it was pure luck if we managed to gulp down any of the warm juice before the departure roll call. Pushed outside in all weather, we would wait for the first of these tedious headcounts that gave measure to our days. The columns moved off at daybreak.

As we made our way to the great exit gate, our throats were knotted up with fear. Fear of revealing that we were exhausted or sick, or simply fear of being noticed, singled out from the herd. Companions who were worn out stayed behind, and we would not see them again.

This morning, in Auschwitz, our group was directed toward the rocks. We would break them, move them left or right, at the whim of the organizers. In Ravensbrück2 I would go to the sand pit. In Nordhausen3 I would twist bolts in an aircraft factory. In Zillertal,4 I would snap yarns and shuffle bobbins in front of a loom. In Frankfurt, I would lay tracks toward an airfield. Dogs and guards saw to it that we stayed pointlessly productive.

At noon we put down our tools to swallow a ladleful of clear gray soup while standing, dreaming that we could sit down. Our faces and gestures could not hide our exhaustion and suffering. Dry lips barely moved, and heaven was already opening in the looks of some seeking help or the end. Yet we could do nothing; our voiceless eyes were our only connection. It was painful and shocking to watch them die in silence. I clenched my teeth: “No, not yet!”

Work ended when the day did. At the great entry gate, the same looks searched out our every weakness, and the same careless gestures pointed us toward death. We straightened ourselves up and looked forward to another tomorrow—one at least as awful as today.

We stood, waiting endlessly for our evening soup and a morsel of bread. A long roll call, the last cracks of the whip as we got back into our hut, then we sank with the sun.

![]()

LICE

I remember those tiny, ingratiating, tenacious little bugs that teased me, nibbled me, and devoured me for many long months.

They were of different sizes, colors, and families. There were the rather plump black ones who moved around so slowly but who stopped only to nip you in some choice location. The white ones were thin and transparent and huddled together in the seams of our clothes. Others were voracious and agile, with their yellow heads and black bodies, and sprawled around in our wounds, having a feast without giving a thought to their host.

With them around I was never bored. If one group had had its fill, another would be hungry again and take over. The lice were there day and night. They became inquisitive with time and familiarity. They had the audacity to parade themselves right under the nose and beard of the SS,5 who, being elite souls and the epitome of cleanliness, could not bear to see them. A thorough disinfection was called for.

Naked and trembling, we clutched our bundles of old clothes as a huge concrete belly swallowed us up. A vat for the clothes and a cold shower for us, then a procession in front of a bicycle pump that spat out some white mist. A puff on the right and a puff on the left then out we came laundered, shorn, frozen, and crying with impotence as the audience laughed at us. Each of these sessions was also a highly risky moment of selection. If we had the misfortune to let ourselves be overwhelmed by hunger or the smell, dogs were there to bring us back in line.

At the end of the session, they would throw clothes to us over a small fence. Those rags were never the right size. As we waited for the others outside we tried to swap them with each other, an operation that itself had risks, what with the barbed looks that surrounded us. Sometimes I pulled it off. However, it also happened that I would come back at night wearing a dress with a train and with shoes the size of boats on my feet. Those who organized our stay took great delight in seeing us in such outfits.

Our little black, white, or two-tone guests waited for us in the straw in our huts. They were angry that we had left them to fast for so long. Filled with desire they came back to us.

![]()

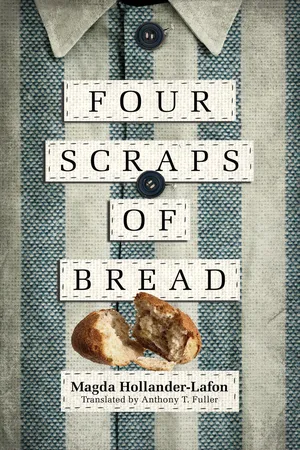

BREAD

The value of a morsel of black bread in the palm of my hand: a little bit of life that I stared at devouringly.

Crumb by crumb I ate it, making it last. I closed my eyes like a newborn so that I could savor it and let myself be immersed in its flavor.

If I were not vigilant, someone might take it from me, seize hold of my life, just like that, without warning: every man for himself. I needed to be willing to fast for many days if I wanted to survive.

You had to know how to keep your eyes open to spot a peeling that had escaped from one of the bins, the way you would scoop up a drop of dew nestled in the bottom of a shell.

Hunger made me dizzy. I saw mirages, and stars flashed in front of my eyes. I spent all my energy chasing away visions of plates, cooking, and meals in an effort to calm my imagination. This was an enemy I fought against every day.

For all that, I do not envy those who have never known hunger, because they will never know the joy of a crumb of bread.

![]()

FEET

My feet bore the weight of an entire life. I often begged them not to let me go. They went through every season of the year under a gray, forgetful sky.

Our bodies walked on despite us, and thousands of feet made themselves move forward against all reason. It was better not to know why, or what fate they were dragging us toward. We were well aware that if our feet refused to walk, other feet in black shiny boots would be ready to finish us off.

At the great entry and exit gate we had to run. It was an almost daily routine, to check if we were still fit for work. Icy robots stood on either side of the gate, armed with whips, dogs, and sticks. We ran, numb with fear. To lighten our run, and to avoid being bitten or beaten, we abandoned our shoes and clogs. If we slowed down or stumbled, a stick would immediately hook us and pull us off to one side—chosen for death. The women bringing up the rear of this long column would bump into lifeless bodies and trip over random obstacles.

With wild and flailing steps we kept on running past the gate, breathless and driven by instinct, our faces stiff with fear.

Our lives depended on our feet. They were painful and disturbed our short nights. At every daybreak we wonder...