![]()

CHAPTER 1

Ways and Means

Methodology

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.

—Hamlet, act 2, scene 2

If thou wilt, I will go into the field, and glean the ears of corn that escape the hands of the reapers.

—Ruth 2:2

Art history as a discipline could be said to be somewhat obsessed at this point in its evolution with methodology, how one goes about the task of explaining images.1 It is incumbent on practitioners of the craft to be more transparent about what it is they are doing. At times this can take on an overly personal, confessional tone, but, be that as it may, I shall say a few things about how I have proceeded in this endeavor.

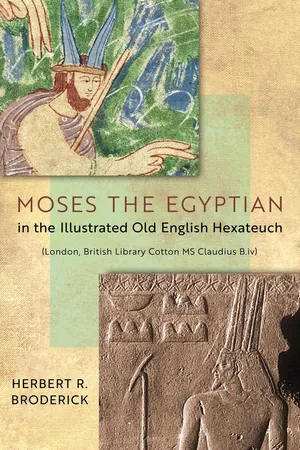

Two extensively illustrated Old Testament manuscripts other than psalters survive from late Anglo-Saxon England: Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 11 (formerly referred to as the Caedmon Manuscript), of about 1000 or slightly earlier,2 and London, British Library Cotton MS Claudius B.iv, of about 1025, also known as the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch, formerly as the Hexateuch of Aelfric or as the Aelfric Paraphrase of the Pentateuch and Joshua. Differing in style, technique, format, and iconography, the manuscripts are similar in terms of the large number of illustrations they contain (48 in Junius 11, 394 in Claudius B.iv), as well as the fact that they both accompany Old English texts based on the Bible rather than the canonical Latin text of the Bible itself. Both manuscripts have been generally attributed to the monastic scriptoria of Canterbury, either St. Augustine’s, in the case of Claudius B.iv, or Christ Church, with respect to Junius 11, although various other locations have been suggested for Junius 11.3 While my focus here is Claudius B.iv, it is useful to compare how the artists of both manuscripts deal with some of the same material.

Both Junius 11 and Claudius B.iv have been the subject of intense study since the late nineteenth century, and the bibliography on both manuscripts is extensive.4 The most recent studies of the illustrations of both works, that of Catherine Karkov on Junius 11 and Benjamin Withers on Claudius B.iv,5 have, for critical and ideological reasons, moved away from the focus on nineteenth- and twentieth-century source study (Quellenforschung) and have chosen instead to explore the role played by the illustrations in both manuscripts as an integral factor in the construction of their meaning and to explicate, especially in Withers’s study, the readerviewer’s experience by exploring in depth the phenomenology of the act of seeing and reading. Karkov and Withers have focused on the manuscripts and their illustrations as reflections of late Anglo-Saxon culture, its Sitz im Leben, as well as the manuscripts’ role in shaping that culture. Some scholars may be of the opinion that the kind of detailed source study that dominated later twentieth-century investigations of these two manuscripts has exhausted the possibilities of what some might even consider an ill-advised undertaking in the first place. However, as I hope to demonstrate, there is still much to be learned about the origin of many of the most distinctive features of these complex and richly illustrated works. While the search for “sources” can seem to be an end in itself, my purpose here is to ascertain to the extent possible what it is that the artists of Claudius B.iv have done to alter and utilize their “sources” to create something entirely new, serving often quite different purposes.6 It is an exaggeration to think of all utilization of sources, even in the highly tradition-minded culture of the European Middle Ages, as slavish “copying.”7 Often the most innovative creative work, even in modern and contemporary art, has “appropriated” and altered to different ends earlier motifs and compositions.

In his book Bring Out Your Dead, Anthony Grafton makes the observation that “in the fiercely competitive German universities and academies, in particular, those who could slaughter their intellectual ancestors stood a better chance of prospering than those who worshipped them”8 While not lapsing into thoughtless idolatry, I hope, methodologically I am following in the footsteps of three very traditional and, at present, unpopular paradigms: the tripartite “iconological” schema of Erwin Panofsky, Kurt Weitzmann’s much-criticized “picture criticism,” and Franz Joseph Dölger’s “Antike und Christentum” approach. While these methodologies are not without their shortcomings, important features of each for the art historical enterprise are perhaps being too quickly pushed aside. The importance of accuracy of observation in Panofsky’s first, or “pre-iconographic,” level of interpretation is still essential even if there are epistemological issues with his second and third “levels.”9 While Panofsky would no doubt agree with St. Paul that in the iconological enterprise we may be at best only able to “see through a glass darkly” (per speculum in aenigmate; 1 Cor. 13–12), the so-called new art history may run the risk of seeing only itself.10

In terms of “seeing through a glass darkly,” in the context of manuscript studies, it is worth recalling the perceptive remarks of Harvey Stahl relative to the question of the role played by earlier “exemplars” and “Weitzmannian” “models,” that “the utility of these manuscripts to any discussion of models depends upon one’s ability to read the contemporary style and to discount the artist’s updating or mannerisms or the impact of other models.”11 This proves to be especially true in the case of Claudius B.iv’s model, or models. Particularly apropos of this study are the words of Massimo Bernabò about the relationship of the Byzantine Octateuchs to their original models: “Over the course of centuries the changes accumulated so considerably that it becomes impossible to get a clear picture of the archetype. One can perceive it only at a distance, as if through a veil.”12

Try as they may, none of Weitzmann’s critics has thus far presented a coherent, thoroughgoing methodological substitute for the major outlines of his approach developed in his magisterial Illustrations in Roll and Codex, especially his concept of “migrating” imagery.13

In the pursuit of tracing sources for many of the specific peculiarities of individual images in Claudius B.iv, I have found Dölger’s Antike und Christentum approach of great assistance. The implications and meaning of this approach are many but might briefly be summed up by Edwin Judge’s assessment of Dölger’s methodology as stepping “beyond the traditional use of patristic writers as sources” and turning instead “to the vast fund of non-patristic sources that lay ready to hand in the apocryphal or Gnostic writings, in the inscriptions, papyri and monuments.”14 In addition, the writings of the first-century C.E. Alexandrian Jewish exegete Philo have yielded important interpretive details especially relevant to a fuller understanding of some of the illustrations of Claudius B.iv, as I shall demonstrate in the case of the representation of the four Rivers of Paradise and Balaam’s dream in addition to specific details of the characterization of Moses. Jewish legendary material in midrash and haggadah has been helpful in a number of specific instances,15 but it should be kept in mind that a good deal of this Jewish exegetical material was well known to Christian writers and exegetes. As untutored as I am in it formally, I have learned perhaps the most, on my own, from the work of scholars in the field of history of religions, from whom art historians in the fields of ancient and medieval art also have a good deal to learn.

Much, of course, has changed in the past three decades in the art historical enterprise, as it must. There are now a number of new methodological “strategies” and trajectories: intensified interest in the “social” history of art and questions of gender, race, and class. Some may see a study such as the present one of iconographic sources as a bit old-fashioned, yet there is much to be learned about works of art by looking for sources of imagery where justified in order better to understand just what is unique and creative about how later artists transformed these sources to serve different expressive ends and purposes.

The whole question of the relationship of the medieval manuscript artist to “models,” “copies,” and “exemplars” is hampered by an essentially nineteenth-century Romantic view of artistic creativity and individualism.16 We can no more imagine a medieval artist sitting down to illustrate a text,17 especially that of the Bible itself or something based on the Bible such as Claudius B.iv, and simply using whatever images come to mind any more than we can imagine a medieval theologian or exegete setting out to explain a biblical text by using whatever he thinks of at the moment. That does not rule out that both individuals, the artist and the theologian, might have a storehouse in memory of images and interpretations absorbed from preexisting paradigms.18 But “sources” can be dealt with creatively, just as a “source” can be misunderstood or consciously contravened. In the end, what matters most for us is what the medieval artist has done with these sources, as no one is suggesting, I should think, that the artist is merely copying.19 The operative term in contemporary artspeak is appropriation,20 whether it is our eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon monk or a twentieth-century Picasso.

Working within a biblical concept of the fullness of time (kairos), this study of the illustrations of Claudius B.iv, and specifically the representation of Moses, has benefited greatly from important previous studies, and study aids, that have appeared in the intervening period. Paramount among a number of outstanding publications are Weitzmann and Kessler’s study/reconstruction of the Cotton Genesis (1986),21 Weitzmann and Bernabò’s publication of the Byzantine Octateuchs (1999),22 Bernabò’s important study of the fundamental role played by pseudepigrapha as a source for extrabiblical details in Early Christian and later medieval manuscript illustration,23 Kessler’s study of the Carolingian Bibles from Tours (1977),24 the immensely useful Ikonologie der Genesis (1989−95) of Hans Martin von Erffa,25 Richard Gameson’s The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church (1995),26 Catherine Karkov’s 2001 study of Junius 11,27 and Benjamin Withers’s 2007 study of Claudius B.iv,28 to name but some of the most salient works that have appeared over the past three decades. Michelle Brown’s The Book and the Transformation of Britain, c. 550–1050 has done much to clarify a number of larger issues concerning the interaction of word and image.29 In terms of conceptualizing how such a “radical” and “appropriated” visual construction of Moses such as I have discerned in the illustrations of Claudius B.iv could have been possible, I have found particularly enlightening M. David Litwa’s 2014 study, Iesus Deus: The Early Christian Depiction of Jesus as a Mediterranean God. Thanks to the outstanding work of Bernard J. Muir,30 whose digital version of Junius 11 has made full-color images of the manuscript with commentary and scholarly apparatus available on CD-ROM, in addition to the Bodleian Library having made available the entire manuscript in color on its website, the full-color CD complete facsimile of Claudius B.iv published by the British Library, and the latter’s publication of the complete full-color manuscript on its website,31 these two extraordinary manuscripts are now available to a potentially global audience. The time seems ripe for a broad-based, detailed, additional look at what the artists of Claudius B.iv have accomplished in terms of how they have contrived to provide suitable images for the manuscript set before them, with specific emphasis on the representation of Moses.

The literature on both Junius 11 and Claudius B.iv is quite extensive as they have been the focus of scholarly attention, at least in the case of Junius 11, since the seventeenth century. I am especially appreciative that I have the benefit of hindsight and have been able to construct my work here on a foundation of important and careful work. I am especially indebted to the pioneering work of George Henderson,32 whose studies of these two manuscripts have been a constant source of enlightenment even when, from time to time, I may disagree with some of his findings.

And finally, I have ...