![]()

PART 1

The Novel as Climate Model

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Realism after Nature

Reading the Greenhouse Effect in Bleak House

When Esther Summerson, the orphaned, intermittent narrator of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1852), first arrives in London with her escort, Mr. Guppy, the city appears to be on fire:

I asked him whether there was a great fire somewhere? For the streets were so full of dense brown smoke that scarcely anything was to be seen.

“O dear no, miss”, he said. “This is a London particular.”

I had never heard of such a thing.

“A fog, miss,” said the young gentleman.

“Oh indeed!” said I.1

Esther and Guppy’s conversation dramatizes the central questions of this book: What does it mean to imagine a manufactured climate? How do we dwell, meaningfully and coherently, in an abnatural world? These are questions of urgent, twenty-first-century significance, but they are also questions that we share with the Victorians. Residents and visitors alike apprehended the metropolis as a quintessentially new environment, one in which every blade of grass or drop of rain bore the imprint of human action and within which the very parameters of life, space, and time underwent radical transformation. Esther arrives as a stranger not only in the city but also in the Anthropocene. In that regard, we have a great deal in common. Treating Victorian literature as Anthropocene literature offers a paradoxically new perspective on the present, reminding us that we inhabit the future: we live after the end of the world to which our bodies, appetites, and ideas are adapted, in a state of perpetual withdrawal from the world we once called home, even as many of the species with which we cohabit the planet disappear entirely.2

Guppy betrays the degree to which inhabiting an artificial climate demands a cultivated inattention to the unthinkable. Esther’s initial impression recalls the worst disaster that had ever befallen the city, the Great Fire of 1666. The term “London particular,” with its wonderful evocation of the particulates in London’s air, is often misattributed to Dickens because of this scene. It actually appeared as early as 1825, when one C. Lamb described “the true ‘London particular,’ so manufactured by Thames, Coal Gas, Smoke, Steam, and Co.—None others are genuine.”3 The term is thus replete with the “particulates” in London’s air, and explicit about the metropolitan climate as a manufactured thing. Nonetheless, Guppy’s use of it proves inadequate to the task at hand because it describes a phenomenon as familiarized out of his own consciousness as it is foreign to Esther’s. Naming becomes a way of abdicating a responsibility to explain: the London particular has simply become the new normal, even though Esther had never heard of such a thing. Guppy’s response begs (and receives) no further inquiry beyond “Oh indeed!” And yet Esther is right. There is a “great fire somewhere,” or at least a great many fires burning in innumerable hearths, steamships, locomotives, factories, and gasworks of what Alice Meynell would later dub “the smouldering city.”4

A CLIMATE FOR ALL NATIONS?

As a stranger in London, Esther was not alone. In October 1850, the satirical weekly Punch ran an article titled “Climates for All Nations” that lamented an oversight in hospitality toward visitors to the upcoming Great Exhibition: many foreigners would have difficulty adapting to the climate of London. Mr. Punch proposed hiring Joseph Paxton (the architect who designed the Crystal Palace) to build a series of glasshouses imitating the climates of the world. “By a well-contrived arrangement of large conservatories, every human being under the sun might have been accommodated with his own climate.”5 Despite the tongue planted firmly in his cheek, Mr. Punch highlights the connections between London’s emergence as a global metropolis and the central ontological dilemma of anthropogenic climate change: that climate, long the paradigm of that which lies beyond human influence (let alone control), has become an ideological thing.

Mr. Punch’s proposal inverts the history whereby the glasshouse (also called “greenhouse” or “hothouse”), a technology developed to grow plants far from their native climates as European explorers returned home with flora and fauna from the distant reaches of the globe, found its most enduringly remembered manifestation as a temple to the arts of industry in the Crystal Palace, built to house the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851. Victorian glasshouses created what Isobel Armstrong calls “fictive space,” populated by actual living organisms existing, adapting, and above all performing the laws of nature.6 As William M. Taylor explains, the glasshouse became “one of a number of practical or technical means whereby a new kind of scientific truth—a new kind of visibility—was made possible … a catalyst for novel ideas like the adaptation of living beings to their surroundings.”7 The glasshouse created a space that was fictive not merely in its artifice but also in its visibility, in the sense that everything that occurred within it was staged, in the manner of a scientific experiment.8

This experimental facet of the glasshouse as a model of the environment offers a productive backdrop against which to reexamine the realist novel.9 Drawing a correlation between realist fiction and the glasshouse suggests that we understand Victorian realism as a distinct participant in “environmentalism,” in the nineteenth-century sense of the term, which James Winter has described as “an interpretative framework: the proposition that crucial aspects of human life and history are determined by distinct physical settings.”10 Instead of expressing explicit concern about the vulnerability of the natural world, environmentalism offered the Victorians a mechanism for understanding the relationship between the human species and its habitat in dynamic interaction. Glasshouses were known as “artificial climates,” a paradoxical term that highlights the degree to which they created a space in which nature could be artificial. Plants—whether hybrid, grown out of season, or cultivated far from their native habitats—could be removed from nature and yet continue to live. The glasshouse literalized the abnatural as a condition in which nature exists apart from itself, the quintessential habitat of the Anthropocene.

Punch’s fantasy offers a useful point of departure for tracing the emergence of anthropogenic climate change. Victorian London constituted a new kind of human habitat, “beyond both city and nation in their older senses.”11 The metropolis altered space, rendering it simultaneously compressed, with over a million humans dwelling within a relatively small geographic area, and expanded, enveloping the globe in networks of extraction and exchange. As Tanya Agathocleous has shown, for many Victorian writers, London was the world.12 The scale of the metropolis demanded a new mode of seeing, one that Raymond Williams calls “metropolitan perception,” characterized by “cosmopolitan access to a wide variety of subordinate cultures,” and in the process thus brought into being a nascent planetary consciousness.13 The Crystal Palace epitomizes this scenario as at once metonym and metaphor for the world-as-glasshouse. Plans for the full development of artificial climates in glasshouses would have included, in the words of John Loudon, Paxton’s rival master of glasshouses, “examples of the human species from different countries imitated, habited in their particular costumes, and who may serve as gardeners or curators of the different productions.”14 The thin film of glass thus crystallizes the divide between the “examples of the human species” adapted (and bound) to particular climates and the citizenry outside able to gaze on them, nominally freed from such constraints. Every nation has a climate, just as every nation will have manufactures on display at the Great Exhibition, but it is only in London that climate can be manufactured to order. London’s climate becomes defined neither by its salubriousness nor by its Englishness but by its modernity, the degree to which it exists apart from the laws and rhythms of nature, or, perhaps more accurately, the degree to which those processes continue even in an artificial environment. Modernity is an abnatural condition, encoded in a rupture as utter and complete as it is transparent and invisible. The Punch article makes readily apparent the extent to which the new modes of seeing and dwelling demanded by the metropolis must attend not only to cultures and commodities but also to species, habitats, and climates. Refiguring metropolitan perception as abnatural ecology adjusts the relationship between cultural and natural hybridity in light of new cross-fertilizations bred in the hothouse of modernity—precisely the kind of perception enabled in conservatories and glasshouses, in which exotic species were cultivated far from their native climes.

Glasshouses also rendered visible the contact and contagion entailed in sharing the air. The contained microclimate of the glasshouse was suffused with exhalations. An article in Dickens’s Household Words described the efforts to manage “the condensed breath of all nations” in the Crystal Palace.15 The fact that there is only one atmosphere—the membrane that encompasses Earth, divides it from outer space, and contains our emissions—means that questions of atmospheric disturbances aggregating into climatic change are in some sense always already global. Ice cores taken at the poles show a sharp spike in carbon content in the middle of the nineteenth century.16 Thus, as the works of industry of all nations were assembled in the Crystal Palace, the effluence of industrial modernity was already enveloping the farthest reaches of the globe in a greenhouse of a different sort.

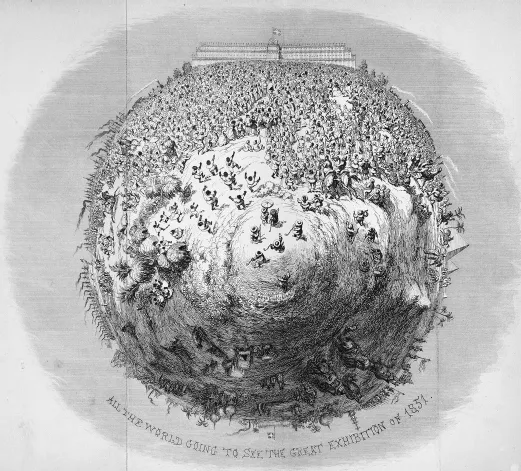

Figure 1. “All the World Going to See the Great Exhibition of 1851,” George Cruikshank. A telltale atmosphere hovers around the image, as though woven from the threads of smoke trailing from numerous chimneys. (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Closer to home, the Punch article intimated an inconvenient truth: the climate of London was inimical to life, no matter whether foreign or domestic, human, animal, or vegetable. The plants housed in such artificial climates needed to be sheltered under glass not only because they were far from their native habitats but also because the smoke and soot-choked air of the metropolis made it impossible to grow much of anything, native or otherwise, in the environs of London. The artificial climate of the glasshouse offered a paradoxically more natural habitat than the soot-laden London fog.17 The city had become a space in which nature could be sustained only through artifice, sheltered from the toxic atmosphere outside the glass.

Perhaps the most striking correlation between the contained environment and the glasshouse came in an argument about the dynamics of Earth’s atmosphere itself, first advanced in 1824 by John-Baptiste Joseph Fourier.18 In 1859, John Tyndall demonstrated the differential heat-trapping properties of what we now know as greenhouse gases. He struggled to conduct his experiments “without impediment from the chimney pots of London,” where he performed his research.19 In 1884, William Ferrel described the effect of Earth’s atmosphere as similar to “the glass covering of a conservatory of plants.”20 By the end of the century, scientists such as Svante Arrenhius and Nils Ekholm were speculating that increasing the concentration of atmospheric carbon through coal combustion might raise the surface temperature of Earth.21 They presented the idea hopefully. Like the creators of the glasshouses on which the theory was modeled, these scientists equated it with control. The world would literally become like a greenhouse or conservatory, in which climate could be regulated as a means of fending off the next ice age and expanding the temperate and habitable areas of the globe. The point here is not to suggest that these theories represent the idea of global warming as we now know it.22 Focusing too much on this largely speculative notion distorts the differences between nineteenth-century science and present concerns, and in so doing obscures the imaginative process whereby climate and human society were beginning to appear as mutually influential. The greenhouse effect was (and remains) a far more complex, troubling, and fertile idea than the familiar association with atmospheric warming would imply, as evident in the range of meanings invoked by synonyms such as “hothouse” and “hotbed.” No sooner are the exotics placed under glass than they intimate threats of hybridity and miscegenation through uncontrolled, accelerated, and abnatural breeding. Indeed, one feature of Mr. Punch’s fantasy is that it keeps the “invasive species” (whether human or botanical) contained behind glass.

The glasshouse literalizes the sense of removal from nature I am attempting to capture with the abnatural. Peter Sloterdijk points to the Crystal Palace as the paradigmatic image of the “world interior” of capitalism, the point at which “the principle of the interior overstepped a critical boundary,” beyond which it “meant neither the middle- or upper-class home or its projection onto the sphere of urban shopping arcades” but instead made “both nature and culture indoor affairs.”23 To inhabit an interior is to imagine an exterior, even if you do not have access to it. We are now in a glasshouse that we cannot escape, even as we are unable to forget the vantage point of one outside looking in. Part of the enduring appeal of nature and wilderness is that they provided this sense of an exterior, at least for some of us, at least for a while.24 Space continues to offer the dream of a “final frontier.” Indeed, the yawning gulf of a black hole may well encapsulate wilderness, Nature, and divine mystery all at once—uninhabited, unimaginable, conceivable only in negation. But this is cold comfort. More to the point, it does not offer us a way forward here on Earth. This is why we need abnatural ecology: dwelling from the inside out, making do with what we have instead of dreaming of lands yet unpillaged over the horizon (or beneath the melting ice pack). Welcome to the greenhouse!

THE NOVEL AS CLIMATE MODEL

Bleak House’s query, “What connexion can there be?,” is the prototypical question of anthropogenic climate change. The linkages between the coal mine and the light switch, the air conditioner and the melting ice cap, are distributed through a network of human and nonhuman actors that defies experiential understanding. While the weather is immersive and immediate, climate—the aggregation of weather patterns over time and space—is an abstraction that cannot be experienced firsthand. Any phenomenology of climate change thus inheres in an eerie disconnection from sensate experience. A similar disconnection also pertains to causes of global warming, the millions of insignificant acts through which the entropy of everyday life wreaks havoc on the atmosphere. The anthropos in anthropogenic (or Anthropocene) is always an “us”—and often implicitly a “them”—rather than an “I.”

This state of affairs demands a rethinking of agency, which can no longer be understood as the exclusive province of the individual (or exclusively human) subject. To dramatize such “distributed agency,” Jane Bennett draws on Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the assemblage, an entangled collective of human and nonhuman actors displaying emergent properties that cannot be reduced to the sum of its parts. The assemblage thus offers a useful mechanism for understanding not only the distributed, multispecies, multisubstance agency of communities, corporations, cities, power grids, ecosystems, and storms but also the composition of complex organisms themselves.27 A whale ship is an assemblage; so is a whale.

The distributed agency of assemblages provides a useful conceptual rubric for reevaluating the weird, abnatural realism of Charles Dickens. In literary terms, distributed agency and vicarious causation are closely aligned with metonymy, which is to say association by proximity (whether physical or conceptual), as opposed to metaphor, which operates through resemblance or shared characteristics. Metonymy attends to both the causal relations and unintended consequences that adhere to objects and ideas. Metonymy is also unstable, and changes over time as terms and concepts find their way into new circumstances and take on new associations. Metonymy is contingent, arbitrary, adjacent, elusive—in a word, atmospheric. Dickens, a “master metonomyst,” inscribes people, animals, objects, and language itself in vast recursive networks of cause and effect, woven out of what Elaine Freedgood calls “the vagrant processes of … the metonymic imagina...