![]()

1

“THE TRUE RUSTIC ORDER”

Log Cabins in Time and Place

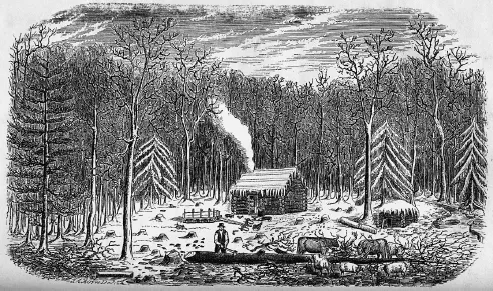

In 1849 Orsamus Turner, a newspaperman in New York State, published a sequence of drawings depicting pioneer settlement in his Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase. The first image depicts a small clearing in a large forest (fig. 5). In the foreground, a man is trimming an already felled tree. In the center is a small log cabin with icicles at the eaves and smoke pouring out of its chimney-less roof. Large round logs, notched at the corners, form the walls. The author informs us that “the roof of his house is of peeled elm bark; his scanty window is of oiled paper. . . . The floor of his house is of the halves of split logs; the door is made of three hewed plank[s]—no boards to be had—a saw mill has been talked of in the neighborhood, but it has not been put in operation.” A woman stands in front of the cabin, feeding chickens and pigs in the yard. The labor of carving this homestead out of the forest is evident in the stumps scattered around the yard and the size of the trees. But Turner reassures us: “The task before him is a formidable one, but he has a strong arm and a stout heart, and the reader has only to look at him as he stands in the foreground, to be convinced that he will conquer all obstacles.”1

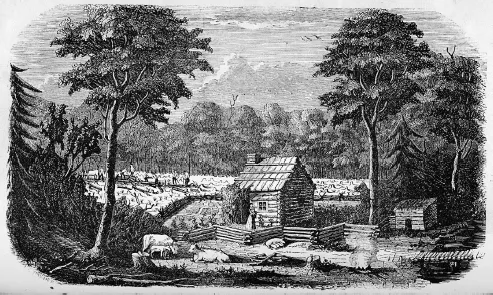

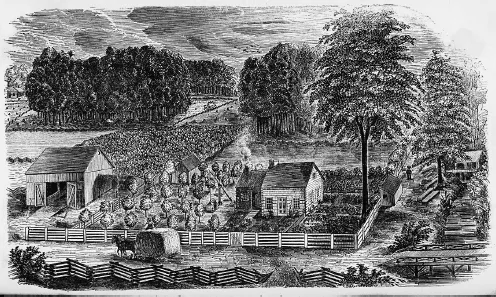

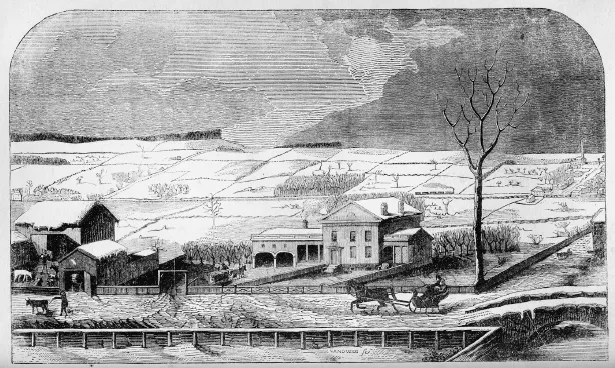

The second drawing depicts the same scene, but in the following summer (fig. 6). A stick chimney has been added to the house, the clearing is much larger, and a fence surrounds the yard. The wife has planted flowers and vines, and she holds a baby. This scene shows the same level of development, evidence of hard work, and pioneer fortitude as the Currier and Ives print “A Home in the Wilderness” (see fig. 1). The third image depicts the scene ten years later (fig. 7). A hewn-log house with multipaned windows and a masonry chimney has been added to the original log cabin, because the farmer “has had too much reverence for his primitive dwelling to remove it.” A framed barn and extensive fields and fencing demonstrate the family’s prosperity. The log schoolhouse in the far left distance indicates that the settlers are no longer alone but are part of an organized community. Finally, by the fourth image, depicting the homestead forty-five years after the first drawing, the original log cabin has been demolished and a fashionable Greek Revival house stands in its place, the farmer’s reverence for the log cabin apparently forgotten (fig. 8). The forests are no longer in the picture; cultivated fields stretch off into the distance, along with a small village on the far right. Our farmer has achieved success: “He has more than comfortable farm buildings, orchards, and fruit yards; the forest has receded in all directions; he is prosperous in the midst of prosperity.”2

Figure 5. “The Pioneer Settler.” Orsamus Turner included a sequence of drawings in his 1849 Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York that depicted the progress narrative of the log cabin. (J. A. Ayres, delineator, Turner, Pioneer History, opposite p. 562)

Figure 6. “Second Sketch of the Pioneer.” By the following summer, the pioneers have added a stick chimney and flowers by the door. Their neighbors are helping them clear land through a “logging bee,” which occurs in the background. (Turner, Pioneer History, opposite p. 564)

Figure 7. “Third Sketch of the Pioneer.” Ten years later, the pioneers have added a large hewn-log section onto the original round-log cabin, and they have cultivated and fenced the land. (Turner, Pioneer History, opposite p. 565)

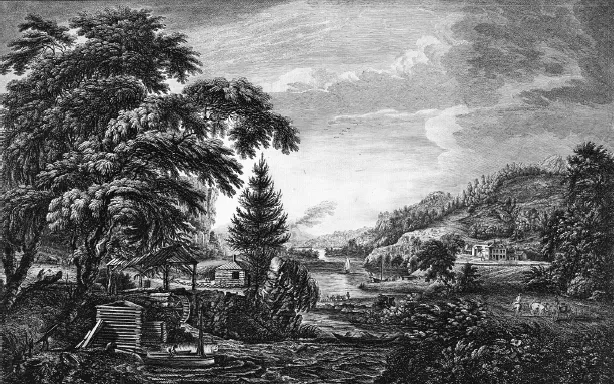

The sequence of images depicts the progress narrative of brave pioneers settling in hostile and isolated surroundings, gradually civilizing the land around them and making a good living for themselves and their progeny. The role of the log cabin is literally front and center; it is the building that both reflects its surroundings, by being constructed of the material that dominates the first image, and enables the transformation, by being an inexpensive, expedient, and temporary form of building. One compelling idea about the log cabin was that it was part of a transformative process, perhaps not intended to last forever or even into the next generation, but enabling a family to take root (fig. 9).

Figure 8. “Fourth Sketch of the Pioneer.” Forty-five years after the first settlement, the pioneers have replaced their log cabin with a fashionable Greek Revival house. Cultivated land stretches into the distance. (Turner, Pioneer History, opposite p. 566)

Movement characterizes the log cabin in several ways. One is this idea of sequence, a family moving from a log cabin to a better house. A second form of movement is change over time and space. Called “the architecture of migration,” log cabins as a building type suited migrating peoples. They were built of local materials with relatively little effort, utilized trees that had to be cleared anyway, and could be easily left behind.3 As the architecture of first settlement, the log cabin crops up in different places as settlement spreads. Where first settlement occurs varies along with when—generally moving westward from the East Coast in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but also northward, southward, and eastward, not reaching interior parts of Alaska and the West until the twentieth century. The forms of log cabins reflect their places, responding to hot climates or heavy snowfalls in different ways. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, technological innovations also affected the log cabin.

Figure 9. “A design to represent the beginning and completion of an American Settlement or Farm” shows a log cabin on the left, behind the mill, and a two-story frame house across the river. This 1761 drawing is one of the earliest depictions of the progress associated with the log cabin. (Paul Sandby, delineator, from a drawing made by Governor Thomas Pownall, Library of Congress)

This chapter begins by defining and describing the log cabin and its characteristics. Next comes a short discussion of its origins and diffusion, followed by an assessment of its dominance on the built landscape, as a type that housed probably half the population in 1800. The chapter concludes with an account of how the log cabin varied through the centuries and across the country.

DEFINING THE LOG CABIN

In its examination of the log cabin, this book focuses on buildings with horizontal logs notched at the corners. There were other ways to lay logs, of course. Various forms of vertical log construction were popular among French colonists. Jacal, another form of log construction, in which vertical poles were lashed together and daubed with mud, was common in the Southwest. Palisade walls were familiar to Native Americans as well as European colonists. Short lengths of logs laid transversely created a stovewood wall, a form of building that required a great deal of mortar.4 Logs could also be laid longitudinally, yet not notched at the corners. Instead, other methods would join the logs to vertical posts: mortise and tenon, nailing the logs to the posts, or nailing vertical pieces to the posts to hold the logs in place. Yet it was the notched, horizontal logs that dominated log construction in the United States, both in actuality and in the public mind.

The “cabin” part of a log cabin also requires some explanation. Fortunately, Thaddeus Mason Harris, a Unitarian minister, provides a fine distinction between a log cabin and a log house in his description of an 1803 journey in southwestern Pennsylvania:

The temporary buildings of the first settlers in the wilds are called Cabins. They are built with unhewn [i.e., left in the round] logs, the interstices between which are stopped with rails, calked with moss or straw, and daubed with mud. The roof is covered with a sort of thin staves split out of oak or ash, about four feet long and five inches wide, fastened on by heavy poles being laid upon them. ‘If the logs be hewed [i.e., squared]; if the interstices be stopped with stone, and neatly plastered; and the roof is composed of shingles nicely laid on, it is called a log-house.’ A log-house has glass windows and a chimney; a cabin has commonly no window at all, and only a hole at the top for the smoke to escape. After saw-mills are erected and boards can be procured, the settlers provide themselves more decent houses, with neat floors and ceiling.5

Harris’s description nicely dovetails with Orsamus Turner’s drawings: a log cabin is crude, window-less and chimney-less, built of round logs without nails or sawn lumber (fig. 10). A century later, the same temporary function of a round-log cabin persisted. In the Appalachian community of Hollybush, Kentucky, “pole houses” of round logs laid directly on the ground were perceived as provisional shelters, replaced within a year or two by hewn-log houses supported by stone foundations.6

Figure 10. “Log House in the Forests of Georgia” pictures a log cabin with round saddle-notched logs, few if any windows, no foundation, and a board roof supported by purlins. (Basil Hall, Forty Etchings, from Sketches made with the camera lucida, in North America, in 1827 and 1828 [Edinburgh, 1829], Library of Congress)

A log structure that a builder intended to last a while—which Harris called a house—was constructed more carefully, maybe with a stone foundation, hewn logs, and dovetailed notching. Log buildings that needed to be secure, such as jails, garrison houses, and storehouses, were constructed even more carefully, with tightly fitted logs that could not be breached. Log houses survived at a greater rate than cabins, so Americans often remember the basic log cabin as being more finished than it usually was. As both Harris and Turner pointed out, it also could be upgraded over the years, turning the cabin into a house.

The appellation “cabin” gradually became applied to more than the minimal, window-less and chimney-less building. As cabin took on more romantic connotations, as explored in this book, the building also took on a window and a chimney and other features, so that the log cabin of popular memory resembles the Currier and Ives version (see fig. 1) more than the Orsamus Turner one (see fig. 5). In the nineteenth century, as long as people were building their cabins out of necessity, they tended not to call them cabins, which had derogatory connotations. Only in retrospect, perhaps, would the log building acquire the name cabin with romantic, even desirable, associations.

The decision to build in log resulted from many factors, with availability of trees and familiarity with the form chief among them. Simply stated, log cabins were built where there were trees. Because of the weight of the logs, if they had to be moved any distance to a cabin site, it was easier to saw them and build a wood frame. And once settlement spread westward to the treeless Great Plains, log construction was no longer the best option. If trees were available, a builder might consider log construction if there were no sawmill or if he had no cash with which to purchase sawn lumber. It was, of course, possible to produce sawn lumber without a sawmill. Whipsawing or pit sawing, involving two people pulling a long saw down a length of timber, could produce planks. The work was difficult, however, and the log cabin avoided the necessity. Also, the use of a sawmill was usually predicated on money, so cash-poor homesteaders found the log cabin an expedient solution. There were always home builders who preferred log construction, despite the option of a sawmill, because it was solid, durable, and energy efficient.7 There were also reasons to build log cabins that had nothing to do with practicality, and subsequent chapters consider these more romantic and nostalgic associations.

The debate over the amount and kind of labor needed to build a log cabin has often overlooked its varying complexity. The log cabin could be built by just one or two people, if the logs were fairly short and the notching was simple. Help in the form of a work party was always desirable, though (fig. 11). In that case, preparing the logs on the ground and notching them was done ahead of time; then neighbors were brought in to hoist them into place in the walls. In this way, a log cabin could be “built” in a day, but the day included only erecting the walls and roof framing; a great deal of work before and after that one day was necessary. Hewing the logs square would involve additional time and labor, but perhaps only a few days’ worth. The expertise inherent in some notching types suggests that professionals were required. Some accounts describe “corner me...