![]()

CHAPTER 1

Carl Sandburg and the Living American City

On 15 June 1896, a young Carl Sandburg made his first trip to Chicago. While overwhelmed and energized by the electric buzz of the city, he was deeply moved upon reaching the sprawling shore of Lake Michigan, the fifth-largest lake in the world: “I walked along Michigan Avenue and looked for hours to where for the first time in my life I saw shimmering water meet the sky. Those born to it don’t know what it is for a boy to hear about it for years and then comes a day when for the first time he sees water stretching away before his eyes and running to meet the sky” (Always the Young Strangers 379). The contours of the city are embedded in this brief description. From Michigan Avenue, a major and often congested thoroughfare downtown in the 1890s, Sandburg could pivot and see the huge expanse of the lake reaching endlessly eastward. This vantage point captures many contradictions that Sandburg would later explore in his verse, particularly his fascination with Chicago as both urban and natural at once. While readers most often associate Sandburg with the grit of a swiftly industrializing metropolis, his poetry reveals an intertwined preoccupation with the organic matter of the city, such as the sky, mist, waves, and mud most often associated with nature. For Sandburg, the mechanical and built features of Chicago were never to be understood in isolation from its elemental character, nor could the city be clearly distinguished from the prairies and farmlands to the west and the lake stretching out to the east.

This vision of Chicago, one where nature and culture meet in an urban garden on the edge of a shining lake, was promulgated and, in part, realized by Daniel Burnham, the father of American city planning and author of the Plan of Chicago (1909). The Plan articulates not only Burnham’s vision for holistic design in its attempt to meet the needs of Chicagoans through fully integrated urban infrastructure but also voices a persistent concern for the place of nature in this urban context. Increasingly, that context was the defining characteristic of American life as the populations of cities swelled dramatically from 1890 onward. Burnham’s Plan combines an emphasis on nature’s function in healing city dwellers and democracy with an attempt to reconceptualize nature as an urban phenomenon. Specifically, the Plan provides several ways of imagining the new natural city of modern America. Burnham presents the city as a living organism, one that breathes with green lungs, thereby emphasizing holism and the interrelation of parts. As a living thing, the city and its components are materially dynamic, as in Burnham’s description of a living lakefront. As a space, the city is characterized by permeability achieved by reconsidering the relationship of interiors and exteriors. Just as Sandburg could stand within the busiest district of the city and marvel at the openness of sky and water, Burnham also imagined Chicago as both enclosure and out-of-doors simultaneously. Nature, once associated with a wilderness “out there,” beyond the interior of the city, is now imported within city limits through the creation of a large public park system, one that preserved the vistas of Lake Michigan from encroaching sprawl. These parks not only bring the outside in but also make present the past by reconstructing a vanishing frontier experience within city limits.

In one sense, Sandburg’s work represents a key moment in the reception of Burnham’s Plan. He lived in Chicago during an era when the Plan, in its various iterations, saturated newspapers, lecture halls, classrooms, movie theaters, and art galleries. As Burnham’s philosophy permeated the air of the city, his design began to alter Sandburg’s urban landscape bit by bit, and so the poet had to physically negotiate Burnham’s aesthetic and social ideals as they materialized as an architectural text. What Burnham dared in concrete, Sandburg attempted in verse. Like the Plan, Sandburg’s poetry depicts a porous city where organic and inorganic, interiors and exteriors, light, weather, steel, and smoke constantly test and interpenetrate each other’s boundaries. In another sense, Sandburg’s poetry presents a significant revision of Burnham’s aesthetic as it eschews finality and holism in favor of process and heterogeneity. This emphasis on process in the poetry draws from Sandburg’s experience of the city as a material text in flux, one constantly written and revised by workers tearing apart streets, welding girders for bridges, and filling in the lakefront with debris. By focusing on labor, Sandburg potently captures the shifting and disintegrating borders between urban and natural environments within the parks, streets, buildings, and utility lines of Chicago. He ultimately presents the city as that continuous act of shifting, rather than imagining a final, stable state, as is expressed in the Plan.

Similarly, rather than elevating the figure of the planner, designer, or architect, Sandburg presents working Chicagoans as most intimately involved in the daily material exchanges that create this intricate urban ecosystem. Sandburg’s understanding of the city as an ongoing physical process, rather than a finished product, weds with his concerns as a socialist. While Burnham was often criticized for overlooking the details of working-class living environments, Sandburg sees Chicago as an environment everywhere permeated by working-class labor. However, this focus on materialization over conceptualization, concrete and mud over the drafting board, does not wholly undermine city planning. On the contrary, Sandburg praises planning as a uniquely Chicagoan form of work and often blends together architects and laborers, blueprints and bevels, in his depiction of construction work. And yet, while Burnham busily advertised the Plan, his design only mattered to Sandburg in its matter: the cycles of sweat, salt, and steel that would embody and yet never perfectly realize Burnham’s vision.

That vision had implications far beyond the borders of Chicago. When the Plan was made public on 4 July 1909, to much well-orchestrated fanfare, the choice of date communicated the document’s broader national importance. With the loss of the frontier, long associated with wilderness and American character, and a corresponding explosion in urban populations, a nationwide environmental and civic crisis faced leaders in city governments and urban reform movements. Between 1800 and 1900, the proportion of the American population living in cities skyrocketed from 3 to 40 percent (Smith xv). And Chicago exemplified these national trends. Within two generations, the city transformed from a frontier town situated on ill-drained prairie, with a population of 4,179 people in 1837, to the second-largest city in the United States by 1890, outdone only by New York. Between 1880 and 1890 alone, the city’s population had doubled, totaling 1,100,000. By 1909, it had doubled again, reaching nearly 2 million inhabitants.1 Sandburg was one of those millions who poured into the city looking for fresh opportunities. Born in the small town of Galesburg, Illinois, Sandburg eventually abandoned a life of piecing together manual labor (as a milk truck driver, coal heaver, and field hand, to name only a few of his positions) in order to explore his options as a writer in the big city. His cry of wonder before Lake Michigan, and his poetic oeuvre as a whole, bears the marks of this emigration from a rural habitat. It is as a newcomer, one not “born to” Chicago but who had “heard of it” throughout his childhood, that Sandburg celebrates the Second City. His perspective as a transplant also allows him to appreciate Chicago as a prairie native like himself: a creature thoroughly modern and yet grounded in a pioneer tradition, made of equal parts macadam and clay, bricklayers and farm boys.

Just as Sandburg attempts to preserve Chicago’s frontier heritage and organic character in his depiction of its most modern elements, so too was Burnham anxious to integrate the spirit and texture of the plains into the urban habitat that threatened to destroy it. This anxiety was rooted in a shared national concern over civic virtue, particularly how the loss of nature in its manifestation as frontier would weaken American democratic temperament and result in an enervated population. As Burnham notes, the time for awe over sheer, unordered expansion had come to an end: “The people of Chicago have ceased to be impressed by rapid growth of the great size of the city. What they insist asking now is, How are we living?” (32). The Plan contains a litany of harms resulting from poor planning, including pollution and traffic congestion, violence and crime, mortalities due to lack of sanitation, and the general ill health and declining moral character of the working class (32). Nor was the Great Fire of 1871 far from memory. Shortly after the devastating blaze, the nationally acclaimed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted argued that the fire might have been prevented entirely if the city had had a better plan (Smith 8). With the overtaxed and outmoded construction of a former trading outpost buckling under its swelling population, Chicago became both emblem and laboratory for the new discipline of city planning. If the first generation of American city planners regarded the poor arrangement of urban centers as the cause of nearly every physical and democratic ill, they simultaneously imagined the well-planned city as a cure-all.2 Burnham, and the City Beautiful movement in general, assumed that simply dwelling in or moving through lovely spaces would infuse proper feelings in the citizen.3 In arguing that the loveliness of urban centers resulted in proper civic behavior, city planners moved democratic education from the active homesteading of pioneers to the passive reception of cityscapes crafted by specialist designers. Sandburg also vacillates between deep concerns over the unwholesome, cramped environment of the city and optimism about the restorative effects of its open spaces and wide vistas. He similarly shares Burnham’s holistic understanding of urban environments and translates that planning philosophy into ecosystemic and organismic presentations of the city on both the macro and micro scales: from gigantic presentations of the city and its skyscrapers as bodies or watersheds to a tight focus on the particulate materiality of individual moments of exchange, like a girder rusting or flecks of sand drifting in the electric light cast from buildings. In some pieces, such as “The Harbor,” Sandburg shares Burnham’s ideology about the psychological effects of passively consuming certain kinds of spaces. In others, he shifts the perceived benefits of working the land, the task of the now vanished pioneer, onto the business of working steel and concrete, thereby recuperating the character-building functions of actively shaping one’s environment within an urban context.

A close study of the Plan, as a series of documents, a public discourse, and a spatial text in the making, elucidates Sandburg’s specific engagements with and revisions of Plan principles, as well as his negotiation of the actual changes in landscape they precipitated. What follows is a brief history of the Plan that explores Burnham’s design in order to contextualize how his presentation of the nature/city relationship finds expression within Sandburg’s verse. However, reading Burnham alongside Sandburg invites a reconsideration of scholarly assumptions about Burnham’s conception of nature as well. This ecocritical and textual approach to the Plan exposes Burnham’s developing understanding of postfrontier nature as an architectural and deeply human artifice that must be built into American cityscapes.

THE PLAN OF CHICAGO: THEORIES AND MATERIALIZATIONS

The Plan of Chicago, a 164-page document three years in the making, creates not only a proposal for the arrangement of the city but also a nascent history of city planning that takes Chicago as its ground of origin: “The origin of the Plan of Chicago can be traced directly to the World’s Columbian Exposition. The World’s Fair of 1893 was the beginning, in our day and in this country, of the orderly arrangement of extensive public grounds and buildings” (Plan 4). While Burnham might here be accused of immodesty (as he was one of the principal architects of the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893), the fairgrounds did serve as a design exemplar for city planners who believed that its popularity would also inspire the nation to address the ramshackle development of its urban centers (Boyer 46). However, providing a start date for city planning as a discipline involves several difficulties. City plans in a global context long predate Burnham’s efforts. Within the Plan, Burnham acknowledges the influence of the second-century Spartan planner Lycurgus and takes the Paris of Napoleon III as the ideal city. By evoking this long history, Burnham legitimizes his principles by gesturing toward a classical lineage. And yet, on the other end of the timeline, official city-planning periodicals, such as the Century, World’s Work, and Journal of the American Institute of Planners, let alone professional degrees, would not become available until the 1930s (Boyer xi). That being said, when considering city planning as an American movement that culminated in a specific discipline with shared theories, the 1893 World’s Fair served as the watershed moment. By 1909, Burnham can already demonstrate the Fair’s lasting influence on the national landscape: “From Providence and Hartford in the East, to Kansas City and on to Seattle in the West, city planning is in full progress. The South also has felt the impulse” (28–29). What these individual efforts in urban improvement had in common with each other and with the vision presented at the World’s Fair was an underlying principle of unity: “There had arisen the conception of the city as an organic whole, each part having well-defined relations with every other part; and the expression of this idea is now seen to be the highest aim of the city-builder” (29). This foundational principle regards urban environments as organic wholes and set city planning apart from earlier piecemeal municipal improvement plans that failed to address the interconnectedness of city spaces.

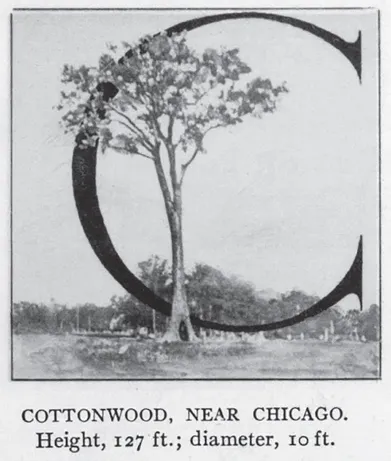

Burnham’s organic approach and the centrality of nature in his design philosophy is writ large in even the smallest details of the Plan. In the handsome and luxuriously expensive first edition, jewel-toned, light-daubed maps of an imagined future Chicago are augmented by ornamental capitals at the start of each of its eight chapters.4 The word “CHICAGO” begins four chapters, with the imposing C at times standing against miniature maps veined with proposed streets and railways. However, in chapters 3 and 6, the C fronts images of trees: a stately and shady boulevard in chapter 6, and a botanical example of the American cottonwood in chapter 3. Beneath the cottonwood, Burnham supplies the only note on a capital illustration in the entire volume, turning the word “CHICAGO” into a miniature field guide for native trees: “Cottonwood, near Chicago. Height, 127 ft., diameter 10 ft.” (32). This is the first chapter to begin with the name of the city and so graphically announces “CHICAGO” by visually equating it with an icon of nature. The note emphasizes actuality, suggesting a real tree with measureable dimensions and a specific location, while “CHICAGO” hovers between the present and the possible future, referring to both the city in its current, unruly manifestation and the dream of a city yet to be realized. The cottonwood, “near Chicago,” exists both inside and outside of the city, visually part of “CHICAGO” while simultaneously located in a vague periphery in the note, proximate and far at once. This two-way act of writing Chicago onto nature and nature onto Chicago blurs the limits of urban and natural environments.

A decorative capital letter C with cottonwood and taxonomic note that begins chapter 3 of Burnham’s Plan of Chicago. (Courtesy of the Newberry Library of Chicago; call case #fW999.182)

The presentation of the letter C, a minute part of the complex visual and lexical rhetoric of the Plan, is emblematic in more ways than one. As a symbol within the Plan, it represents Burnham’s vision of the city as an organism reliant upon natural spaces and materials, parks and plants. More broadly, Burnham’s recurring C-for-Chicago, mingled with maps and leaves, performs city planning’s attempt to imagine and craft fit places for man and nature. Altering preconceptions about the mechanized character of city life is at the heart of Burnham’s philosophy, though Burnham had difficulties letting go of language that emphasized a split between nature and city. While Plan scholars, such as Carl Smith, demonstrate how Burnham often falls into traditional conceptions of nature as an anti-urban, preindustrial out-there, the Plan simultaneously pushes against this tendency by placing nature within the city and equating that integration with the very essence of city planning. Rather than undermining the Plan, this vacillation reveals a larger national reconception of urban spaces in the early process of articulation. If C is for Chicago, it must be for cottonwood as well; otherwise, in the minds of the first city planners, they were both in danger of permanent erasure.

Chicago’s topography provided a clean page for this new inscription. Just as Sandburg marveled at the wide lakefront, Burnham regarded the flat expanse of Midwest plains meeting the reflective sweep of Lake Michigan as a tabula rasa: “Whatever man undertakes here should be either actually or seemingly without limit” (Plan 79). The tension between “actually or seemingly” limitless planning is captured in the preexisting landscape. On the one hand, the openness of land- and waterscapes emphasized the horizon, creating a boundless canvas on which the urban architect might work: “Here the city appears as that portion of illimitable space now occupied by a population capable of indefinite expansion” (80). However, in actual fact, the landscape presented planners with real limitations. Burnham held that any plan must take local topography into account, and thus while it might seem that anything is possible on the prairie, in reality the design must mimic the contours (or lack thereof) of the local environment: “Whatever may be the forms which the treatment of the city shall take, therefore, the effects must of necessity be obtained by repetition of the unit. If the characteristics set forth suggest monotony, nevertheless such are the limitations which nature has imposed” (80). “The unit” here refers to the gridiron pattern of plot division that characterizes most frontier towns. The flat lines of the plains perfectly lent themselves to just such an arrangement. At their worst, they suggested monotony, but at their best, the gridded streets reflected the expansiveness of the site: “Always there must be the feeling of those broad sur...