![]()

LISTENING

Critical Engagements

![]()

“THIS CLASS OF PERSONS”

When UVA’s White Supremacist Past Meets Its Future

LISA WOOLFORK

What we view as racial progress is not a solution, but rather a regeneration of the problem in a particularly perverse form.

—DERRICK BELL

The past and the future merge to meet us here / what luck / what a fucking curse.

—WARSAN SHIRE, “INTUITION”

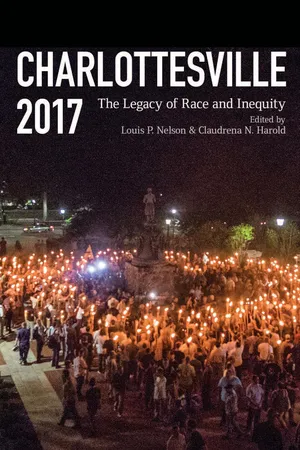

Charlottesville faced a two-pronged assault from white supremacists who rallied in the city on August 11 and 12, 2017. Their strategy of attack was to strike at the heart of Charlottesville by breaching the Rotunda, the University of Virginia’s symbolic center, and by violating the center of the city itself with incursions in parks, parking garages, and downtown streets. That weekend, an allied group of Nazis, neo-Confederates, fascists, white supremacists, and unaffiliated racists converged on Charlottesville to ostensibly protest the removal of a Confederate monument from the city center. The August 2017 rallies were the culmination of what some local antiracist activists called the “Summer of Hate.” Beginning in May 2017 Charlottesville faced monthly white supremacist rallies with varying degrees of spectacle and severity. Leading white supremacist and UVA alum Richard Spencer held what has now become known as a “torch rally” in May. Several dozen white supremacists holding lit torches and chanting “white heritage” slogans surrounded the Robert E. Lee statue. In June 2017 a small group of neo-Confederates convened at the Lee statue only to be met by clergy and local residents who joined hands for songs, chants, and prayers. In July 2017 a Ku Klux Klan group from North Carolina rallied in Justice Park to protest its recent renaming. (The park was formerly called Jackson Park in honor of the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, whose statue is installed there.) These events and their mobilization around the removal of Confederate monuments that enshrine white supremacy laid the foundation for the more prolonged action scheduled for August 11 and 12, called Unite the Right. The Unite the Right participants, orchestrated by UVA alum Jason Kessler, assembled in Charlottesville for a weekend of sustained pro-white activism. It all culminated on Saturday, August 12, when pro-white protesters prompted skirmishes with antiracist activists and black community members, resulting in injuries to dozens of people and the death of one counterprotester, who was killed when a white supremacist drove through a crowd of counterprotesters in a deliberate act of terror.

The most significant precursor to the lethal attack of August 12, however, was the violent white supremacist spectacle at the UVA’s Central Grounds on the evening of August 11. The white supremacists’ fire-fueled march though Grounds and the university’s official responses to it are the focal points of this essay. Specifically, I ask: Why has the university arrested more people for protesting white supremacy than for promoting white supremacy? And what might this discrepancy reveal about the weight that white supremacy continues to bear on university life? Why were three UVA students arrested for trespassing—two black and one white—during the university’s bicentennial celebration, when three hundred white supremacists (not currently enrolled students) brandishing lit torches could march unimpeded to seize the symbolic heart of the university?1 The university’s official statement explains that because the students disrupted a “ticketed event,” they were subject to ejection and legal consequences: “The UVA Bicentennial Launch yesterday on the Lawn was a ticketed event. Any person who interrupts an invited speaker or event shall be requested to leave and removed if they refuse to leave or persist in interrupting any speaker or event.”2 This seemingly neutral preference for order and civility attempts to conceal an important issue that students were trying to address. At the time of their arrest, the students held a large, carefully crafted banner. Styled in a graphic theme similar to the official university bicentennial promotional materials, the banner proclaimed “200 years of white supremacy.” When three currently enrolled students are arrested for trespassing but approximately three hundred white supremacists are allowed to march unimpeded through Central Grounds—bearing lit torches and ultimately attacking students and staff in full view of law enforcement—it raises the provocative suggestion that the students’ banner had the right of it after all.

My essay turns to documents to better understand the persistence of white supremacy at the university. Some of the texts I consider emerge from the historical record, while others are recently written responses to pro– and anti–white supremacist rallies on Grounds. My purpose here is to use the literary studies skills of textual analysis and close reading to better understand how these texts create a discursive landscape that remains complicated by, if not indebted to, the white supremacy from which the university was stamped at its beginning.3 In addition, careful study of these documents, statements, and counterstatements produced by, within, and against the university is part of a moral inventory prompted by the challenges of the white supremacist violence that occurred on our campus and in our city. An examination of select archival and contemporary documents allows us to evaluate the meaning of white supremacists marching on campus. Is this act best described as an anomaly, an invasion, or a homecoming?

It is useful to start at the beginning. On August 1, 1818, the commissioners for the University of Virginia met at a tavern in Rockfish Gap on the Blue Ridge. The assembled men had been charged to write a proposal that would be titled the Report of the Board of Commissioners for the University of Virginia to the Virginia General Assembly, also known as the Rockfish Gap Report. This document would articulate the university’s unique and robust educational mission, which included “to develope the reasoning faculties of our youth, enlarge their minds cultivate their morals, & instil into them the precepts of virtue & order.”4 The collective also articulated a vision of education that specifically affirmed racial and racist hierarchy for its students and the commonwealth. Relying on a horticultural metaphor of a “wild & uncultivated tree” that is ameliorated by merging the “savage stock” with a “new tree,” the report declares that “education, in like manner engrafts a new man on the native stock, & improves what in his nature was vicious & perverse, into qualities of virtue and social worth.” The horticultural symbolism quickly gives way to the racist and eugenic dimensions of education. The commissioners promote the value of higher education by comparing its benefits to those who lack it: “What, but education, has advanced us beyond the condition of our indigenous neighbours? and what chains them to their present state of barbarism & wretchedness, but a besotted veneration for the supposed supe[r]lative wisdom of their fathers and the preposterous idea that they are to look backward for better things and not forward, longing, as it should seem, to return to the days of eating acorns and roots rather than indulge in the degeneracies of civilization.” The rhetorical nature of this question—“What, but education, has advanced us?”—leaves little room for the possibility that structural, ideological, and economic factors “advanced” these scions of the white, wealthy, master class who composed this document. A careful inspection of this report suggests that white supremacy, in theory and in deed, was a requisite foundation for the educational benefits essential to progress.

White supremacy was not only useful for helping to promote the value of the educational mission of the university. This belief system also played a crucial role in locating the physical space that the university would occupy. As the Rockfish Gap Report suggests, in addition to the educational project of the university, the commissioners were required to structure other formal protocols, such as the living arrangements represented by the Pavilions, Hotels, and the Lawn.

Though they considered the power that resided in constructing a radical educational vision previously unknown during their time, the commissioners were also committed to finding the ideal geographical location for this undertaking. Three choices were identified as the most propitious venues: Lexington in Rockbridge County, Staunton in Augusta County, and Central College (Charlottesville) in Albemarle County. Ultimately, however, Central College was deemed the best site on which to build. As the report claims, Staunton and Lexington were also suitable since “each of these was unexceptionable as to healthiness & fertility.” The deciding factor that led the commissioners to choose Albemarle County as the site for the university was exclusively its proximity to white people. The commissioners observed, “It was the degree of centrality to the white population of the state which alone then constituted the important point of comparison between these places: and the board, after full enquiry & impartial & mature consideration, are of opinion that the central point of the white population of the state is nearer to the central college, than to either Lexington or Staunton by great & important differences, and all” (emphasis mine). The Rockfish Gap Report lays the literal and figurative groundwork for the university’s interests in and promotion of white supremacy.

The report reveals the practical ways in which white supremacy was the single most important attribute that explains the university’s current location in Charlottesville. The commissioners made the determination, based on research that was “impartial” and “mature,” to privilege Albemarle County over Lexington or Staunton. Simply put, the University of Virginia was located in Charlottesville because Charlottesville was the site most easily accessed by most of the state’s white people. These white supremacist foundations constitute a fundamental element of the university’s history that curiously anchors expressions of white supremacy on its grounds today.

Scholars at UVA have increasingly documented the impacts of slavery on the university and the degree to which the peculiar institution’s prevalence structured campus life during the antebellum period. Digital projects like The Illusion of Progress, by the Citizen Justice Initiative of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies, offer rich context and archival documentation of Charlottesville’s and the university’s investments in white supremacy. Similarly, Jefferson’s University Early Life (JUEL) database is a thoroughly constructed archive of digitized primary documents, three-dimensional renderings of buildings and other sites, and essays (including nineteenth-century faculty minutes and student commentary). The President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, convened in 2013, was tasked to “provide advice and recommendations on the commemoration of the University of Virginia’s historical relationship with slavery and enslaved people.”5 This essay acknowledges this important work and seeks to amplify the role white supremacy played in these historic formations.

My objective is to understand how vestiges of the original determining factor for the university’s location in Charlottesville—white supremacy as seen in Charlottesville’s “centrality to the white population”—resonate across generations, making contemporary Charlottesville less an idyllic “progressive” town and more a place where its white supremacist roots await activation. One trace element of white supremacy, attributable to the antebellum days, shaped an interpretation of the ways that the neo-Confederates, Nazis, and other white supremacists organized on university Grounds. For the first fifty years of its existence, the university relied on enslaved labor in a variety of positions. In addition, enslaved workers were tasked to serve students personally—cleaning rooms, lighting fires, cooking, running errands, and more. Jefferson believed that allowing students to bring their personal slaves to college would be a corrosive influence, which fit within his paradoxical philosophy in general. Faculty members, however, and the university itself owned or leased enslaved people. This strategy of restricting students’ personal ownership of the enslaved while allowing them access to and reliance on enslaved labor had an even more ...