![]()

1 Big Mules and Bottom Rails in the Magic City

As an industrial city built on its rich deposits of iron and coal, Birmingham has the distinction of being a city whose very name identifies it as a planned city. Named after the industrial city of Birmingham, England, Birmingham was incorporated in 1871 by the Elyton Land Company, which consisted of ten investors. The company purchased nearly 4,500 acres of Jones Valley farmland in Jefferson County, Alabama, where the South and North Alabama Railroad was expected to cross an existing railroad, the Alabama and Chattanooga. The investors were well aware of the area’s rich deposits of coal and iron as the Alabama state geologist had systematically recorded the state’s mineral deposits beginning in the late 1840s.1 So confident were they of the city’s future that at the 1873 annual meeting of the Elyton Land Company, one of the investors, Colonel James R. Powell, described Birmingham as “this magic little city of ours.”2 Birmingham’s enduring if often ironic nickname, the Magic City, was born.

The investors were joined in this knowledge by the South and North’s chief executive, Frank Gilmer, and chief engineer, John Milner. They had ridden over Red Mountain and through Jones Valley before the Civil War and had seen the mineral deposits and imagined the industrial development that would take place there. Milner had been appointed in 1858 as chief engineer to survey the feasibility of building a railroad through the hill country of North Alabama, where the state’s iron and coal deposits were concentrated. His 1859 report to the governor outlined the costs, possible routes, and benefits of building a railroad through Alabama’s mineral region. By demonstrating the feasibility of laying a rail line through North Alabama’s hilly but mineral-rich terrain, Milner’s report caused among railroad promoters a sensation that would last the next twenty years, culminating in the birth and growth of Birmingham in the 1870s.3

Milner’s report made clear that Birmingham would not only be a source of raw materials but would become an important manufacturing center as well. To this end, Milner predicted that mills in the Birmingham area could successfully depend on black workers to perform the arduous tasks of making pig iron and rails. Writing just before the Civil War, Milner saw slavery as compatible with the industrial development of the South and that cheap black labor would be a key contributor to Alabama’s competitiveness in manufacturing.

I am clearly of opinion, that negro labor can be made exceedingly profitable in manufacturing iron, and in rolling mills. The want of skillful labor, has hitherto been the grand objection to the manufacture of rails in the South. This is compensated for by the freedom of the Southern States, from that curse of Northern works, “strikes among their workmen.” Making Railroad bars is a monotonous process. Each bar is the facsimile of the other, and the great labor consists in the heavy lifting, and managing the heated masses in the machines or rolls. It requires no great mechanical skill, even, for every part is done by machinery, which simply requires to be fed. A negro who can set a saw, or run a grist mill, or work in a blacksmith shop, can do work as cheaply in a rolling mill, even now; as white men do in the North, provided he has an overseer—a southern man, who knows how to manage negroes. I have long since learned that negro labor is more reliable and cheaper for any business connected with the construction of a railroad, than white. It is said that there are five thousand pieces in a locomotive, each requiring the nicest adjustment. To make such machinery as this, skilled mechanics are required, and such is the case in erecting fine buildings of lumber, but the lumber can be sawed into boards by ordinary hands, and such is the case in the manufacture of iron into bars.4

Even before the Civil War, Alabama’s rich supply of cheap black labor was seen as instrumental to its industrial development. Horace Ware, a pioneer ironmaker in Shelby County, just south of where Birmingham would be established, had already employed slaves in operating the Shelby Furnace in the 1840s and 1850s.5 Ware was not alone, as blacks were employed in mills, furnaces, tobacco factories, textile mills, mines, steamboats, wharves, and railroads throughout the South before and during the Civil War.6

After the war and the founding of Birmingham, Birmingham’s industrialists were quick to employ black labor in mines and mills. An 1886 account of Birmingham’s industrial development reports that “about 40 percent of the total population of Birmingham is negro. About 90 percent of the labor employed by all the furnaces, near Birmingham, is negro. … Besides the negro furnace labor, much of the labor employed by the city manufacturing industries in iron, such as the rolling mill, foundries, etc., is negro.”7 Just as northern employers preferred European immigrants, southern employers preferred blacks for the difficult, hot, and dangerous work of the mines and mills, believing African Americans to be better suited to such labor than whites.8 James Sloss, who established the Sloss Furnace Company in Birmingham in 1881, told U.S. Senate investigators in 1883 that he would not hire white labor over black: “Well, as a matter of business, I don’t think it would be an improvement to substitute white labor.” In response to a follow-up question, he explained: “Yes; we have got no white labor on our place, though, except skilled labor. The balance of the iron men, the coke men, the yard men, the furnace men, and some of the helpers and stock men are all colored, and that colored labor is as good labor as I want if I could just keep it at work.”9 Birmingham employers also preferred largely black workforces because they feared the social friction that might result from mixing white and black laborers on an equal basis.10 By relying on black workers to do the most unpleasant, physically demanding jobs, Birmingham industrialists believed they also made their white workers more manageable:

The manifest result of the presence of the negro labor here is that we have a more intelligent and orderly white laboring population, than otherwise might be anticipated. The negro here is satisfied and contented; the low whites elsewhere are dissatisfied and turbulent. The white laboring classes here are separated from the negroes, working all day side by side with them, by an innate consciousness of race superiority. This sentiment dignifies the character of white labor. It excites a sentiment of sympathy and equality on their part with the classes above them, and in this way becomes a wholesome social leaven.11

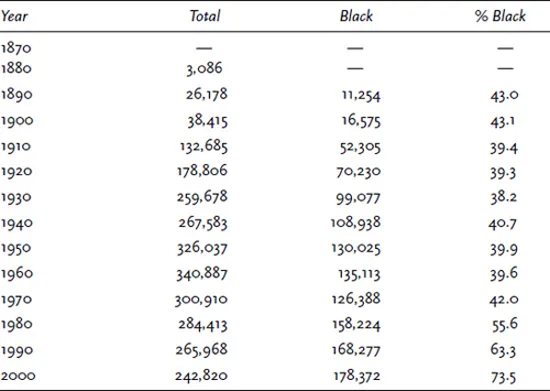

As a consequence of Birmingham’s hiring practices, the city’s black population grew rapidly as former sharecroppers left the cotton fields of the rural South for the opportunity to earn a wage in Birmingham.12 By 1890, when Birmingham’s population had grown to 26,178 from 3,086 in 1880, 43 percent of the population was black.13 As the city’s population grew to a peak of 340,887 in 1960, the black population remained at around 40 percent of the total (see table 1.1). In 1910 and 1920, Birmingham had a higher percentage of blacks in its population than any other U.S. city with 100,000 or more population, and in 1920 Birmingham was the eighth-largest city in the nation in terms of black population. In 1920, only one southern city, New Orleans, had a larger black population than Birmingham.14 From its very beginnings, Birmingham was planned not only as an industrial city but also as a substantially black city.

Overseeing Birmingham’s black population were the city’s industrialists, bankers, and utilities, commonly known as the city’s (and the state’s) “Big Mules.”15 The biggest and most powerful Big Mule firm was Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI), which in 1907 was purchased by U.S. Steel. TCI had bought its way into Birmingham and by 1892 had become the largest iron producer in the South.16 After TCI’s Ensley plant, located just west of Birmingham, began producing open-hearth steel rails in the late 1890s, it gained the attention of the steel-making world when in 1907 the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads placed an order for 157,000 tons of steel rails.17 Facing increased competition for the steel rail market, gigantic U.S. Steel, formed in 1901, bought out TCI in November 1907, placing Birmingham’s largest firm into the hands of the New York financier J. Pierpont Morgan.18

Big Mules such as TCI–U.S. Steel exercised control over both the city’s economy and its politics. Refraining from running for political office, the Big Mules preferred to rely on middle-class politicians to run the city, making sure all the time that the city kept its taxes and expenses low and maintained the separation of the races in all forms.19 According to longtime Birmingham reporter and observer Irving Beiman, “The city’s industrial and financial interests have always insisted on ‘cheap government’ for Birmingham.”20 As a result, whenever Birmingham’s per capita expenditures were compared to those of other cities, Birmingham’s were invariably the lowest. In 1939, for example, the Louisville Courier-Journal compared Birmingham to seven other southern cities and found that Birmingham’s per capita cost of government was the lowest of the eight cities. At $20.15 per capita, it was one-third lower than the next lowest city, Memphis.21

Table 1.1. Total and black population in Birmingham

Source: U.S. Census data as reported at http://www.bplonline.org/locations/central/gov/HistoricalCensus.asp.

The Big Mules also had a stake in maintaining racial segregation. Building on racial antagonism between whites and blacks, Big Mule industrialists could keep unionization in check by making sure that whites had no desire to join with blacks to fight for higher wages and better working conditions. Even when unionization did come to the steel industry in 1937, TCI–U.S. Steel’s settlement with the local Steel Workers Organizing Committee called for using seniority to enforce sharp occupational and wage distinctions between whites and blacks. By maintaining racial segregation in Birmingham, the Big Mules discouraged interracial solidarity in local labor unions, thereby enabling the city’s industrialists to maintain a dual wage system.22

For maintaining the racial status quo, the Big Mules relied on T. Eugene “Bull” Connor, who served as one of the city’s three elected city commissioners from 1937 to 1953 and from 1957 to 1963. Connor was a radio sportscaster who gained fame for announcing the Birmingham Barons minor league baseball games. His popularity as an announcer provided the support he needed to be elected to the state legislature in 1934. In 1937, encouraged by state senator James Simpson, Connor was elected to the Birmingham city commission as chief of public safety.23 Throughout his career, Connor’s folksy glibness, along with his strong support for segregation, endeared him to the white working classes in Birmingham.24

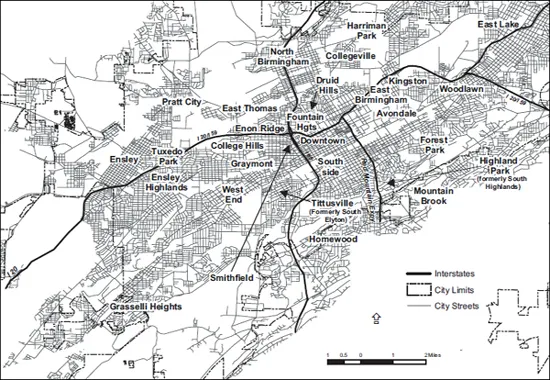

Map 1.1 Birmingham ne...