![]()

Part One

Writers, Film, and the New Visual Landscape of Rio de Janeiro

![]()

1 Documenting New Urban Experiences

The Cinematic Work of the Crônica

Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and our furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have locked us up hopelessly. Then came the film and burst this prison-world asunder by the dynamite of the tenth of a second, so that now, in the midst of its far-flung ruins and debris, we calmly and adventurously go traveling.

—Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”

He goes out, not to review, but to view

The future

That dried up the acacia

and erects iron pyramids out of dust

where a mountain, a family, a child

literally disappeared

and electronic machines emerge.

He is filming

his hereafter.

A stone profile

with no echo.

—Carlos Drummond de Andrade, “Documentário”

BRAZILIAN WRITERS' FIRST ENCOUNTER with film took place in the daily press. Between 1900 and 1910 a number of authors mentioned the arrival and dissemination of what was then called the cinematograph in journalistic essays or crônicas. Artur Azevedo, Olavo Bilac, João do Rio and Lima Barreto all included passing references to the cinema in crônicas written during the first decade of the twentieth century. Such references suggest that by 1910 the new device had become an everyday form of entertainment in Brazil's capital.

A brief glance through journals and newspapers from the period highlights the importance of the cinema in turn-of-the-century Rio de Janeiro. Newspapers contain numerous advertisements for movie theaters; cartoons illustrate crowds rushing to each film performance and journalists also emphasize the medium's increasing popularity in the city. João do Rio observed in the Gazeta de notícias in 1907, “The entire city wants to see the cinematograph…. In every square there are cinematographs attracting thousands and thousands of people.” A 1910 editorial from the magazine Fon-fon! similarly proclaimed, “In Rio de Janeiro, the cinema has already become part of everyone's routine” (qtd. in Gonzaga 104); and the film critic Pedro Lima recalls that in 1908 downtown Rio was often blocked with crowds of people rushing to catch afternoon sessions:

Every Monday, about the time that the movie theaters opened, the Rua Carioca became deadlocked. Audiences from the Iris cinema and the Ideal cinema, which faced each other, flocked together. Movie sessions started at 1 p.m. and they interrupted the flow of the city's traffic. No one could move. (38)

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in depicting and registering life in the capital, cronistas increasingly mentioned the new medium of entertainment, commenting on its growing presence and popularity in the city.

For two writers, however, the movies were more than a novelty to be referenced in passing. At the start of the 1900s Olavo Bilac and João do Rio wrote crônicas focusing exclusively on the cinema, describing the new medium's characteristics and effects in more detail. Common to their descriptions was an emphasis on film's connectivity to contemporary society. In a crônica called “Moléstia da época” (Contemporary Illness) written in 1906, for example, Bilac highlighted the ways in which film engaged with the current times; and in a crônica written in 1909 João do Rio also stressed cinema's engagement with the contemporary environment, arguing that “the cinema is very modern and very up to date. That is its main characteristic” (Cinematógrafo de letras x). For João do Rio, however, the movies were not only linked to the new times; they were also analogous to the very activity of the cronista. So it was that he titled a 1909 collection of crônicas “Cinematographer of Letters,” highlighting both the crônica and film's potential to document the new era.

These two “cinematic” crônicas form the basis of this chapter. I explore how and why these writers perceived the cinema as intimately connected to contemporary society. Moreover, given João do Rio's analogy of the cronista as a “cinematographer of letters,” I also examine the ways in which these writers' experience of the movies underlined changes that were taking place in the field of cultural production at this time, changes that led to a revision of the very concept of literature and the role of the writer.

The Crônica and Urban Life

Before analyzing these texts it is important to chart the development of the crônica in early-twentieth-century Brazil. The journalistic essay, or crônica, has been a significant presence in Brazilian cultural life since the nineteenth century. Appearing in daily newspapers, it provides readers with descriptions and commentaries of “everyday events, of the fait divers, contemporary details that feed the news sections of the daily papers” (Arrigucci 52). In his account of the development of the literary form, Davi Arrigucci highlights how the crônica has changed over the decades, from the descriptive essays by José de Alencar in the nineteenth century to the more satirical crônicas of the present day. These permutations highlight the fact that the crônica is not a static genre but one that is inextricably linked to the cultural and social context that it records. Indeed, Arrigucci links the shifts in the crônica to certain contours of Brazil's social and cultural history. For Arrigucci, this relationship to Brazilian history has made the genre a quintessentially national form.

While recognizing the crônica as a distinctly national genre, Beatriz Resende states that its development and emergence illustrates a “long and impassioned relationship between the city of Rio de Janeiro and the literary genre of the crônica” (“Rio de Janeiro” 35). Referring to Rio as “the city of the crônica,” Resende goes on to point out: “It was in Rio de Janeiro that the genre was born, grew, and established itself” (“Rio de Janeiro” 35). For Resende, the crônica specifically developed to document life in the capital city. “Consequently, the crônica became a register of the city's events, a veritable history of the city, a history of the life of the city, the city transformed into words” (“Rio de Janeiro” 37).

Margarida de Souza Neves also stresses the crônica's unique relationship to Rio. Neves, however, takes this link between the crônica and Rio further by adding a temporal specificity to Resende's more spatial focus. For Neves, the genre was “ardently diffused in turn-of-the-century Rio de Janeiro” and developed in direct response to changes that took place in the capital during this period (77). For Neves, therefore, the crônica emerged not as a Brazilian form per se but as a historical genre whose function was to register “the new life of the city” at the start of the twentieth century (Neves 77).

Nicolau Sevcenko too notes that the crônica proliferated at the start of the 1900s as a result of transformations taking place in Rio at this time (Literatura como missão 30). For Sevcenko, however, far from simply depicting urban changes, the cronista contributed to them.1 Highlighting and praising new lifestyles and spaces in Rio, the cronista, Sevcenko says, helped to justify and articulate the image of the new life of the city (30). The cronista's art form in this sense emerges as a “spatial strategy,” as it contributes to the construction of a new urban landscape (De Certeau 96).

This practice epitomizes the special relationship between literature and the city that Angel Rama has outlined as central to the ideological framework of urban society in Latin America. For Rama, the Latin American city is essentially a “lettered city,” and he emphasizes the essential role writers have had in constructing the urban ideal. This ideal city, operated in an autonomous field of signifiers, stands in contrast to the real city that is operated in a field of people. For Rama, however, the two spaces are not opposed. The ideal city, he says, is not a determining force operating outside of real lived spaces. Rather, both are co-constitutive in a troubled social and spatial dynamic that reveals tensions and contradictions, or to use De Certeau's word, tactics, between a material reality and a discursive dimension. Rama thus describes the lettered city as engaged in “a constant struggle with the material modifications introduced by the daily life of the city's ordinary inhabitants” (28).

This struggle between the material and discursive—between the strategic and tactical—dimension of urban life is, I argue, inherently part of the crônica and informs the very art of the cronista. In documenting life in the capital, the cronista did not stand back and apart from real and lived spaces; he ventured into everyday life, came into close contact with the material city, and provided readers with personal and subjective accounts of its physiognomy. It is this highly subjective aspect of the crônica that Antonio Candido emphasizes, describing it as an intimate literary form that partakes of the context it simultaneously registers (14). The turn-of-the-century cronista thus both gave shape to and was intimately part of the transformations taking place in Brazilian society.

By the early 1900s a crucial aspect of this new society was the cinema; thus, as Bilac and João do Rio documented and described the cinema and its effects, they simultaneously charted and detailed the new social landscape that was emerging in Rio. However, their relationship to this society and film was often problematic, highlighting tensions taking place within the lettered city and its complex relationship to a new material reality.

Cinematic Journeys and Rio's Worldliness

First published in the newspaper Gazeta de notícias on 3 November 1907, Bilac's crônica “Moléstia da época” details the author's first moviegoing experience. Bilac begins by telling the reader, “I am writing this crônica after having returned from a long journey” (195). Citing a number of Rio's streets and neighborhoods, the author appears to have embarked on a tour of movie theaters in distinct areas in the capital: “Avenida Central, Passeio Público, Botafogo, Haddock Lobo, Largo do Machado, Vila Isabel, São Cristóvão, Jardim Botânico, Corcovado, Gávea, Pão de Açúcar” (“Moléstia da época” 196). However, it is soon clear that Bilac's cinematic excursions are not limited to the streets of Rio. Rather, the writer's filmic journey has encompassed a number of different spaces and seems, in fact, to have displaced him from the specific locale of Rio.

My journey lasted only two hours: but, in such a short amount of time I traveled around half of the world: I went to Paris, Rome, New York and Milan. I saw the birth of Christ and his death; I ventured down into a coal mine; I stood beside a lighthouse keeper, right at the top of a lighthouse, in the middle of the crashing waves of the sea; I witnessed a tumultuous strike in France; I saw Kaiser Wilhelm inspect his troops in Westphalia; I saw Samson seduced and defeated by Delilah, and then buried under the ruins of a collapsed temple. (195)

Bilac immediately characterizes his cinematic experience as a journey, one that dislocates him from his immediate surroundings and takes him on a whirlwind tour of distant lands. By virtue of the films he sees, the cronista is transported, not only to different historical times, but also to a number of different sites around the world (Paris, Rome, New York, Milan). This filmic navigation links Bilac to distant places, highlighting the cinema as a site that connects Rio's inhabitants to other foreign cities.

This sense of global connection was not limited to film alone; it was profoundly part of the material culture and urban iconography of the city.2 By the turn of the century Brazil was inserted in the so-called second industrial revolution that marked the start of an intensive phase in the global capitalist system. Searching for new markets for manufactured goods, European nations turned to peripheral regions and countries, like Brazil, exporting consumer items and new technologies in exchange for raw materials, such as coffee. Brazil was thus integrated into neocolonial relations, and as the new century dawned, more and more European goods made their way into the country, most of which entered through the port of Rio (Sevcenko, “Introdução” 514–619). Between 1888 and 1906, the city's port activity rose three fold making it the fifteenth busiest port in the world, surpassed in the Americas only by New York and Buenos Aires (Sevcenko, Literatura como missão 27).

Figure 1. Rua do Ouvidor, photographed by Marc Ferrez. (Acervo da Fundação Biblioteca Nacional—Brasil)

The influx of foreign products and goods in Rio gave rise to what Brito Broca has called a “mundanismo”—a worldliness—as Cariocas were increasingly attracted and attuned to the latest foreign fads and fashions (4). The center of this worldliness was Rio de Janeiro's Rua do Ouvidor.

Stores located on the Ouvidor exhibited the latest French fashions, and curiosity shops displayed myriad technological wonders recently arrived from foreign countries. It was also in a small theater on the Ouvidor on 8 July 1896 that a small audience of Caricoas caught their first glimpse of what was then called the cinematograph, a new invention from Paris. Film thus made its appearance in Rio as another imported product, arriving on board the ships that brought other foreign goods into the country (Bernardet, Cinema brasileiro 11–22). Indeed, the first movie shows were part of a wider display of other foreign curiosities and novelties that audiences would marvel at, such as X-ray machines and phonographs, as well as the latest European fashions—all of which were increasingly available in the capital.3

Yet film was not just implanted in this worldly space; it also contributed to its production. Reporters emphasized the cinema's foreign status, its worldliness cited as the medium's main attraction. One journalist for the newspaper A cidade do Rio wrote, “Yesterday we attended the inauguration of one of the most marvelous spectacles that is, at the moment, eliciting the admiration of audiences in major European cities” (qtd. in Ferreira 18). And a writer for A notícia noted that film enabled Cariocas to experience a medium that “has recently been much admired in Paris and Europe” (qtd. in Ferreira 19). What journalists such as these highlighted was the cinema's ability to enable Cariocas to participate in a medium that was also exciting audiences elsewhere. The cinema was thus clearly attractive in itself and as a foreign import, and its appeal was—above all—the appeal of the other, the elsewhere, or, in Roberto Schwarz's words, the “out-of-place.” Descriptions of the actual images displayed by imported movies such as Snow Fight in Lyon (1897), Iceskaters in London (1897), A Gondola in Venice (1897), and Crowds in the Place de l'Opera in Paris (1898) also emphasized this attraction to the foreign. In 1898 a journalist for the Jornal do comércio described film's ability to “parade before one's very eyes, in their exact dimensions, parts of the boulevards in Paris, with their constant comings and goings, men, women, children, cars, buses, animals, everything” (qtd. in Araújo 9). With its vistas of distant cities, customs, and people, the cinema produced a sense of connectivity that spanned the globe. Such images clearly created the impression that worldliness was not so much “out-of-place” as in place, part of a new material landscape.

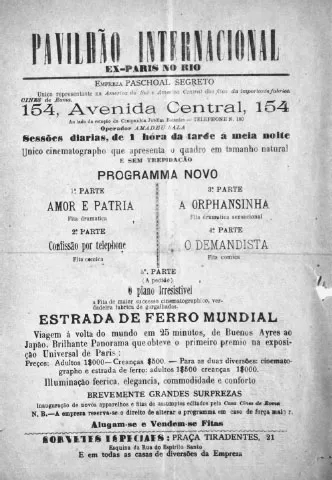

Figure 2. Advertisement for Paschoal Segreto's International Pavilion and Hale's Tour. (Acervo Arquivo da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro)

The cinema thus registered Brazil's insertion in a wider global capitalist system, epitomized by cinema's ability to quickly and easily transport spectators, such as Bilac, to the centers of foreign modern metropolises. The names of movie theaters reinforced this sense of cinema as a site of worldliness. The first theaters in Rio, for example, were the International Pavilion, the Paris Novelty Salon, and the Parisiense. Calling to mind foreign places, the movie theaters were evoked as locations that could transport stationary spectators to different places around the globe even before the film had actually started. Early movie programs also promised to provide spectators with a “journey around the world in 25 minutes, from Buenos Aires to Japan.”

This sense of worldliness characterized the urban topography that was constructed in Rio at the beginning of the twentieth century. Prior to the start of the Republic in 1889, Rio had undergone minor urban transformations. In the 1850s Dom Pedro II ordered the construction of parks and gardens, and around the same time a new port area was developed. With the start of the new Republican regime, however, the project of urban renewal gained greater urgency, part of the new government's attempt to redefine Brazil as a modern nation (Needell 30). Rio's colonial architecture and old structures were seen as out of date, and (perhaps more important) the tight streets and small port made the transfer of consumer products from the city's port difficult, restricting the expansion of commerce, which had become...