![]()

1Latin America as Anachronism

The Cuban Campaign for Annexation and a Future Safe for Slavery, 1848 –1856

IN CINCINNATI in 1851, an Ohioan named William Bland penned a memoir of the last expedition of Narciso López, the Venezuelanborn, self-styled liberator of Cuba who twice tried and failed to forcibly annex the island to the United States. Bland’s sensational book, entitled The Awful Doom of the Traitor; or the Terrible Fate of the Deluded and Guilty, was a record of the defeat and betrayal of López’s U.S. volunteers, supposedly penned by one of their surviving number.

Bland was spared execution under an amnesty issued by the Spanish government to surrendering “filibusters,” as the U.S.-based, proslavery, privately organized militia expeditions to Latin America were called in the United States (though the Spanish newspaper Diario de la Marina simply called López’s men “pirates”).1 The most successful filibuster was the diminutive Tennessean William Walker, whose army briefly occupied Nicaragua in 1856 and 1857, reinstituting slavery and establishing English as the official language. Until he was deposed by a united Central American force, Walker stood, as Brady Harrison writes, “a five-foot-five colossus across the isthmus.”2 López shared Walker’s grand ambitions but never achieved even his modest success. His final expedition ended with the 1851 execution recounted in Bland’s book. In one of its most implausible episodes—the book was printed by a publisher of sensational literature, and it meets many of the genre’s conventions—the Ohioan watches López’s garroting through his prison bars from a point of view high in Havana’s Morro fortress. From this vantage point, Bland sees all. Far below in the city streets, López’s effigy is beaten by angry crowds before the general himself is led to the gallows. Like the public ritual of effigy burning, the execution as described by Bland is an elaborate ritual, redolent of the Catholic superstition and excess that he associates with Cuba. As the crowd looks on, López’s Spanish jailers seal their conquest with the garrote, the execution machine favored by Spain:

López came forth with a firm and steady step, but a pallid face and ascended the platform. His person was enveloped in a white shroud—the executioner then removed the shroud—and there stood the general, in his full military uniform, before the assembled multitude; his appearance was calm, dignified, and heroic, not a muscle quivered. He looked upon the preparation for death unmoved; his countenance remained unchanged, and his whole bearing was firm and manly. The executioner now removed his embroidered coat, his sash, cravat, and all the insignia of his military rank, as a token of his disgrace.

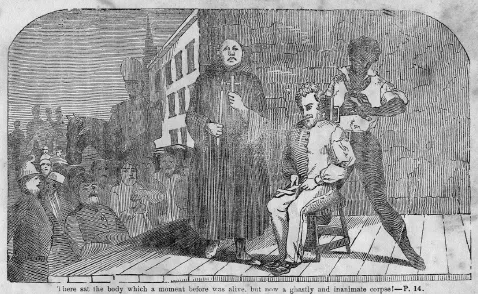

The executioner turns the garrote’s screw, crushing his victim’s throat, and López’s head drops, heavy with symbolism, upon a crucifix held by a priest. “There sat the body,” Bland concludes, “which a moment before was alive, but now a ghastly and inanimate corpse!”3 Just as López’s inanimate head rests in a priest’s hands, so is “the benighting influence of priestcraft resting, like a dark spell of sorcery, upon the whole island.”

An illustration of López’s execution shows an audience of faintly sketched figures watching the proceedings as a soldier on horseback looms in the background. Meanwhile, on the scaffold, the focal point of the image is the seated general framed by two ominous figures. A Black executioner busies himself with the garrote and a fat priest in dark robes sanctifies the entire proceedings, completing the image’s three-part indictment of Cuban society. For Anglo-Americans who supported its annexation, Cuba had long been perceived as a white republic-in-waiting suffering under an ancient European despotism, which offered men like Bland the historic (and lucrative) opportunity to fulfill the United States’ providential mission to free the hemisphere.4 Now, that dream was an “inanimate corpse” resting on a priest’s crucifix. Before this pathetic end, López had been feted by crowds in New York City and courted as a statesman by southern expansionists like Mississippi’s governor, John Quitman. As a postmortem analysis of López’s doomed filibuster and of Cuba itself, Bland’s tale is revealing for reframing as a space of barbarism what had been, mere months before, one of heroic republicanism.

A little-known episode from a failed antebellum imperial adventure is perhaps an unlikely place to begin a cultural history, not only of underdevelopment but of Latin America’s circulation in U.S. culture, given the multitude of successful imperial adventures the continent has suffered. Yet the annexationist episode is exemplary, not only because it shows such an ambitious vision of Anglo-American imperial “futurity,” but also because it demonstrates this vision’s failure. The era of U.S. filibustering and expansion is a historical origin point for the very notion of “Latin America,” a terminology that first emerged at this time as a counterpoint to the militarism of what U.S. expansionists called “Anglo-Saxon” culture. The mid-nineteenth century was a formative moment in the modern geography of the Americas, but the imaginative coordinates of a “modern” North America and a belated Latin America were not yet fixed, as we can see from a careful reading of annexationist discourse. Visions of Cuba as anachronistic competed in this moment with a conviction that the path to North America’s future passed through Havana.

Narciso López at his execution. From William Bland, The Awful Doom of the Traitor, 1852. (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

The imaginative coordinates of northern modernity and southern belatedness that buttress the modern ideology of underdevelopment were as unfixed in this moment as the hemisphere’s political boundaries. Indeed, the conventional use of “expansion” to describe the United States’ mid-nineteenth-century conquests of territory in the Caribbean and the west suggests that the country merely grew to its natural size, like a balloon inflated to its logical limits.5 This “fetishized image of national coherence,” as Mark Rifkin calls the familiar U.S. map, with its coastal boundaries to the east and west, river border to the south in Texas, and straight lines on the Canadian frontier to the north, overwrites indigenous and Mexican geographies and histories and encourages us to think of the nation’s present-day borders as inevitable.6 D. W. Meinig’s multivolume work on the historical geography of the United States, particularly his study of western expansion and filibustering, helps us unthink this geographic destiny. As Meinig points out, there were many possible futures for the hemisphere in the 1840s and 1850s: a “lesser” United States extending to the Mississippi River, with a vast Indian territory across the Rocky Mountains and a Californian Republic in the west, or various versions of a “greater United States” encompassing Cuba, the Yucatán Peninsula, Baja California, Mexican territory south of the Rio Grande River, and parts of present-day Canada.7

Revisiting the notable failures of U.S. “expansion” also indicates the surprising leadership role played by Cuban émigrés in the fabrication of American exceptionalism, which guided Cuban annexation and obviously survived it. For most of the nineteenth century, in fact, white Cubans and Anglo-Americans described Cuba as racially, culturally, and geographically linked to the United States, in ways that have shaped the discourse of inter-American “intimacy.” Cuba has, of course, also played the role of the picturesque exotic and passive beneficiary of U.S. modernity. But in the 1840s and 1850s, Cuba was still widely regarded as what John Quincy Adams, writing in 1823, called a “natural appendage” to the United States. Adams said of Cuba that the United States “cannot cast her off from its bosom . . . looking forward to the probable course of events for the short period of half a century, it is scarcely possible to resist the conviction that the annexation of Cuba to our federal republic will be indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.”8 The midcentury “Young American” expansionist John O’Sullivan saw Mexico, by contrast, as a passively foundational player in the formation of the “great nation of futurity” at midcentury, a vestige of the Old World to be displaced. Cuba, however, was different. In 1852, O’Sullivan’s Democratic Review published an essay on “The Cuban Debate” that presented Cuba as a modern, white country ready to join the Union: “Cuba contains half a million of whites, and is in a perfectly organized state, with her material and other interests, her civil and religious institutions, her manners and customs, her roads and bridges, her schools and churches, her fields of plenty and her climate as matchless as the ground is fertile.”9 Cuban and Anglo-American annexationists insisted alike that Cuba was the path to the future, a conviction that only magnified Bland’s disappointment. Cuba was supposed to be the place where the European 1848 might come to pass in the Western Hemisphere, a place to “carve out fame and fortune with the sword of Liberty,” as another of López’s U.S. volunteers recalled his earlier enthusiasm. Such an opportunity, wrote Richardson Hardy, had not existed “since the Age of Chivalry.”10 Those who opposed annexation, O’Sullivan insisted, were “old fogies” stuck in a rapidly disappearing past. “They are about to disappear before the flood of progress and improvement,” he stormed, “which they do not understand and cannot resist.”11 The island thus summoned a set of unstable temporal and cultural associations in the United States of mid-century: both white and Black, 1848 and “the Age of Chivalry,” the advance guard of history and its priest-ridden junk heap. It is an ideal place, therefore, to begin to explore the singular intimacy of the Americas.

Annexation, La Verdad, and Slavery’s Futures Past

The movement to annex Cuba was at its height between 1848 and the beginning of the United States’ Civil War. For this reason, as Tom Chaffin and Robert May have argued, it has mostly been read as an antebellum curiosity, rarely treated by Americanist scholars outside of the provincial lens of U.S. sectionalism in the run-up to the Civil War—an eccentric project of the Old South.12 Annexation, however, was not merely a regional but also a national and international enterprise, with support from across the United States, especially in centers of Cuban immigration and exile like New York and New Orleans. Determined that Cuba take its place among the revolutionary nations of 1848, Cuba’s annexationists pitted the autocracy of the Spanish colony against the progressive republic to their north. The most prominent annexationist publication, the New York–based La Verdad, spoke on behalf of Cubans and in defense of a flexible vision of “republicanism.”

La Verdad was published in New York every two weeks in Spanish and English between 1848 and 1856, and then briefly in New Orleans before folding. The paper was founded by Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros, an exiled Puerto Príncipe planter and essayist who served as the paper’s principal editor; O’Sullivan of the Democratic Review; Moses Yale Beach, publisher of the New York Sun; and Jane McManus Storm Cazneau, a key ideologue in the antebellum world of proslavery imperialists working to secure a long future and a broad geographic girth for slavery. Cazneau was a former Texas settler, a Sun correspondent in Cuba, Democratic Review editor, and then after the Civil War, a leading advocate of Dominican Republic annexation.13 Under her pen name, Cora Montgomery, she by-lined most of the paper’s editorial articles, in both languages. She likely only wrote the English-language section, however, leaving the Spanish articles to her (mostly uncredited) Cuban colleagues.14 Betancourt Cisneros and Montgomery were joined on the La Verdad staff by Pedro Santacilia, a Cuban exile who later became a high-ranking official in the liberal Juárez government in Mexico, and Miguel Teurbe Tolón, a poet and member of the student-oriented Junta Cubana Anexionista in New York.15 Narciso López’s former secretary, a young writer named Cirilo Villaverde, would later become La Verdad’s editor-in-chief and one of Cuba’s most celebrated novelists. After Betancourt Cisneros’s exile in 1837, he adopted for himself the pen name “El Lugareño,” a colloquial term used to describe a provincial local of some rural place. It was a picturesque and self-effacing nickname for a politically ambitious plantation owner, which captures the Cuban annexationist movement’s embrace of an agrarian patriotism connected symbolically to the Cuban soil. Adopted in exile to establish his local belonging, the nickname calibrates two widely different scales: the global sphere of annexationist politics, and the regional sphere of its imagined Cuba. This was a contradiction that La Verdad tried to manage: to rhetorically align local Cuban desires for “freedom” with the global designs of an expansionist United States.

The newspaper’s purpose was to agitate in the United States, and through illegal circulation in Cuba, for the United States’ annexation of the Spanish colony. If Cuba failed to join the United States, La Verdad suggested, it would mean that Hispanophobes like Bland were right: Cuba might really be condemned to permanent feudal status, languishing in the shadow of its advanced neighbor. One 1852 editorial argued, in English: “If we, Hispanic-Americans, continue under military and theocratic governments, if we do not shake off the aristocratic customs which retain the people in ignorance, in misery . . . this will be precisely to admit of a Providence, preordained and inflexible, that decreed that the United States of America and the American people must be the only great Republic, the only great nation that in the world of Columbus merits the sympathy, recognition, and the respect of all peoples and nations of the civilized world.”16 In placing Cuba, and more broadly, “Hispanic America,” at this historical crossroads, La Verdad challenged its readers to ensure that Spanish America not be left behind by the United States.

In his classic essays “Brazilian Culture: Nationalism by Elimination” and “Misplaced Ideas,” the Brazilian literary historian Roberto Schwarz writes of the anxious self-consciousness of nineteenth-century Latin American elites who measured their nations’ modernity and originality by their adherence to foreign, metropolitan models. Latin America was an “anachronism,” a temporal framework used to compare Latin American social forms unfavorably to the modern nation of “futurity,” as the La Verdad editors do above. Schwarz points out that “anachronism” is based on a false notion of history as a continuity, and of progress as spatially autonomous: spreading, that is, from advanced to backward nations along a timeline that the latter must follow to catch up to the former.17 Dividing the globe into vestigial or progressive, imitative and original, “anachronism” offers a false distinction between capitalist modernity and forms of feudal life, such as theocracy or slavery, that allegedly cannot coexist. As many scholars have argued, such “feudal” barbarities as Caribbean and North American slavery were in fact intrinsic to the formation of the modern world, not exceptional to it. C. L. R. James made this point in Black Jacobins, where he argued that the slaves of Saint Domingue...