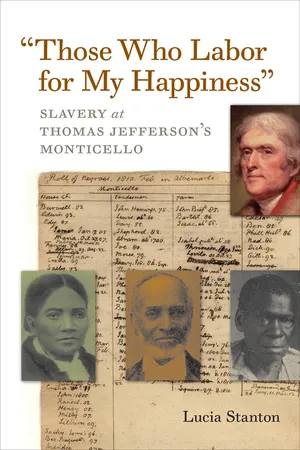

"Those Who Labor for My Happiness"

Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Our perception of life at Monticello has changed dramatically over the past quarter century. The image of an estate presided over by a benevolent Thomas Jefferson has given way to a more complex view of Monticello as a working plantation, the success of which was made possible by the work of slaves. At the center of this transition has been the work of Lucia "Cinder" Stanton, recognized as the leading interpreter of Jefferson's life as a planter and master and of the lives of his slaves and their descendants. This volume represents the first attempt to pull together Stanton's most important writings on slavery at Monticello and beyond.

Stanton's pioneering work deepened our understanding of Jefferson without demonizing him. But perhaps even more important is the light her writings have shed on the lives of the slaves at Monticello. Her detailed reconstruction for modern readers of slaves' lives vividly reveals their active roles in the creation of Monticello and a dynamic community previously unimagined. The essays collected here address a rich variety of topics, from family histories (including the Hemingses) to the temporary slave community at Jefferson's White House to stories of former slaves' lives after Monticello. Each piece is characterized by Stanton's deep knowledge of her subject and by her determination to do justice to both Jefferson and his slaves.

Published in association with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

AAMLO | African American Museum and Library, Oakland |

Bear | James A. Bear, Jr., ed, Jefferson at Monticello (Charlottesville, 1967) |

Betts, Farm Book | Edwin M. Betts, ed., Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book (Princeton, 1953) |

Betts and Bear | Edwin M. Betts and James A. Bear, Jr., eds., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville, 1986) |

CSmH | Huntington Library, San Marino |

DHU | Howard University Archives, Washington |

DLC | Library of Congress |

FB | Facsimile of Jefferson’s Farm Book, in Betts, Farm Book |

FLDA | Family Letters Digital Archive, www.monticello.org/familyletters |

Ford | Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson [Federal Edition], 12 vols. (New York, 1904–1905) |

GB | Edwin M. Betts, ed., Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book (Philadelphia, 1944) |

GWA | Getting Word Archive, Jefferson Library, Monticello |

L&B | Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert Ellery Bergh, eds., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 20 vols. (Washington, 1903–1904) |

LofA | Thomas Jefferson, Writings, ed. Merrill D. Peterson [Library of America] (New York, 1984) |

MB | James A. Bear, Jr., and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767–1826 (Princeton, 1997) |

MHi | Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston |

NARA | National Archives and Record Administration |

NcU | University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill |

PTJ | Julian P. Boyd et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 37 vols. (Princeton, 1950–) |

PTJ-R | J. Jefferson Looney, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, 7 vols. (Princeton, 2004-) |

TJ | Thomas Jefferson |

ViU | University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Author’s Note

- I. Jefferson and Slavery

- II. Families in Slavery

- III. Families in Freedom

- Notes

- Index