![]()

1

FINDING ZION

On a crisp fall Saturday in 2008, following a lead in attempting to locate a “Burton Family Cemetery,” I traveled down a rural Virginia lane to an African American church cemetery. When I arrived, I found the churchyard deserted, with only silent stone sentinels to note my approach.

The gravestones mark each life, often clustered into families, illustrating untold histories. I document each stone, one person at a time. Later, I will upload the photos and inscriptions to a website where I have collected six thousand other memorials from historic African American cemeteries in central Virginia.

I have visited over 150 such cemeteries in a multicounty area; of these, I have documented 118 with maps, photographs, and additional research. This includes more than six thousand individual stones, dating between 1800 and 2000. But many more unmarked or forgotten burials remain to be photographed and recorded. There is no good way to estimate the number of African American burials in Virginia between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but we can review the census figures for one Virginia county and estimate the number of deaths per one thousand individuals per year. The U.S. Slave Census for Albemarle County, Virginia, illustrates that the enslaved population more than doubled between 1790 and 1860, from 5,579 individuals to 13,916;1 the number of deaths would have paralleled this increase in births if it were a closed population with no out-migration. To the contrary, Albemarle County would have experienced in-migration from the Tidewater and out-migration to other southern states (especially Kentucky and Tennessee). Not knowing those migration figures precisely, we can crudely estimate that at least six thousand individuals (or approximately eighty-six per year) died in Albemarle County prior to emancipation while enslaved on a plantation or a small family farm. Only a fraction of their graves have been located.2

Another way to calculate the number of African American burials for a given time period is to search death certificates for the county and add up the number of reported deaths. In Virginia, death certificates were not officially collected until 1912. In Albemarle County, the Charlottesville African American Genealogy Group transcribed 8,088 death certificates for burials that occurred between 1917 and 2001. As a crude estimate of mortality, that translates to ninety-six burials per year over an eighty-four-year period. Hundreds of these individuals lie buried on family land in small, sometimes forgotten graveyards. Sometimes these bodies reemerge in surprising ways, as when an old cemetery is discovered because of a modern construction project. In other instances, remains are lost, forever buried under unmarked ground. We lose important pieces of local and family history when we allow these sacred sites to go unrecorded and disappear.

Origins

In 2001, I was hired to teach at Sweet Briar College, the site of a former plantation willed by its nineteenth-century owner to become a school for women. The college has retained much of its original agricultural land. Hundreds of historic and archaeological sites remain on the three-thousand-acre campus. The plantation owners’ cemetery was well known to the campus community. Every year students and faculty would march up to the plantation graveyard and lay flowers at the grave of the founder and her daughter, in whose honor the school was founded. Situated atop a high hill, containing tall obelisks and surrounded by a stone wall, this cemetery was hard to miss. But the resting place of the enslaved individuals who worked on the plantation had been lost to modern memory.

Fortuitously, a riding instructor at the college had spent years exploring the fields and, just before his retirement, announced the discovery of an unmarked cemetery, overgrown with brush. He had located the plantation’s slave burial ground. As the college proceeded with plans to erect a memorial, I mapped the cemetery and began researching the individuals who were anonymously buried under the gravestones; as is often the case in slave cemeteries, none of the markers were inscribed.

In my research of three dozen antebellum cemeteries, which include 406 individual slave gravestones, I’ve found less than 5 percent of the markers to be inscribed. There are a few explanations for this. A law was passed in Virginia in 1831 that made it illegal to teach “free Negroes” or slaves how to read and write.3 We know from many sources that this law was not always followed, but if you were black and literate, carving a tombstone would be damning evidence to anyone who wanted to make trouble. The urge to carve gravestones is closely tied to a sense of individualism and the desire to know where each individual is buried. Yet within many enslaved communities, kin were forcibly separated through sales, inheritance, or death. Given the fragility of their family structure, these communities developed extended and multigenerational kinship connections to safeguard domestic ties. In antebellum slave graveyards we see this focus on family units rather than individuals in unmarked but uniform stones. These individual yet unmonogrammed grave markers of African Americans would not interfere with mourning practices that were aimed at remembering families. Moreover, this preemancipation tradition of uninscribed stones puts more importance on oral histories, which, among other details, pass down the location of burials from generation to generation. Native and African American communities are known for their centuries-long oral traditions. Our difficulty is in finding a living informant who has preserved such knowledge generations later.

While mapping the cemetery at Sweet Briar, I realized how easily it might have remained buried under leaves and fallen trees, forever lost to the living whose ancestors were buried there. Thankfully, the college realized that it, too, was close to losing a significant part of its history. When I began my investigation of the Sweet Briar site, I could find no existing studies of aboveground remains from slave cemeteries in America, so I attempted to locate another cemetery in Albemarle County, hoping to document what sorts of variations existed from plantation to plantation.4 I had no idea what to expect. Would there be any inscribed graves? Did descendants continue to visit the gravesites? Would it be easy to locate these 150-year-old sites on the modern, often modified landscapes of antebellum plantations?

I concentrated my search for African American cemeteries in central Virginia. Between 2001 and 2011, I visited burial sites, mapping and recording all the aboveground features; collected oral interviews from descendants; conducted archival research of the surrounding communities; and recorded all legible inscriptions from the gravestones. Though often brief and cryptic, these inscriptions can point the way to a wealth of information about the community in which a person lived and died.

Most gravestones compress a life story into a name and date of birth and death, but with additional archival research, an individual’s passage becomes part of a larger story—a story of families and neighborhoods, successes and failures. Sometimes the impact of a single life is still felt today, far beyond the grave site.

Burton Family Cemetery

Some of my methods are necessarily more intuitive than scientific. Small family cemeteries in particular are rarely noted on topographic maps. In 2008, on that fall day when I went in search of the Burton Family Cemetery I’d seen mentioned in several funeral records, I used a method that works about half the time: I checked a map for roads named after the family. These roads often correlate with homesteads and thus with family burial grounds.

In this case, by researching the death certificates for the Burtons, I knew they had died in Albemarle County, so I’d already narrowed my geographic search. I quickly found a road named “Burton Lane” in the county atlas and began driving up and down the road, searching for any signs of a graveyard: a fence, markers, or even a sign.

After driving back and forth for about thirty minutes, I noticed a two-foot-long sign that read “Burton” in the front yard of a modest yellow 1950s ranch house. I could not believe my luck: how many people signpost their surnames in the front yard? For all I knew, the Burtons had moved out decades ago and the current owner had simply neglected to take down the sign, but it was the only lead I had, so I pulled into the driveway. Fortunately, the elderly woman who came to the door was indeed a Burton—Virginia Burton—and she’d lived in this rural neighborhood for fifty-three years. Her husband of forty-five years, Curtis, had died in 1998.

As Mrs. Burton recounted a brief family history, my eyes scanned her crowded living room. If gravestones provide permanent family memorials, the material culture within our houses provides an ephemeral one. I saw dozens of family photos—on the walls, stuck under glass on side tables—and knickknacks of all sorts. On every available horizontal surface sat a glass menagerie of animals, from domestic to exotic. Virginia’s faith was also clearly on display, in objects ranging from a prominently placed Bible and a pair of black angels to religious inscriptions and wall hangings that encouraged the viewer, “Don’t Quit.”

Zion Baptist Church

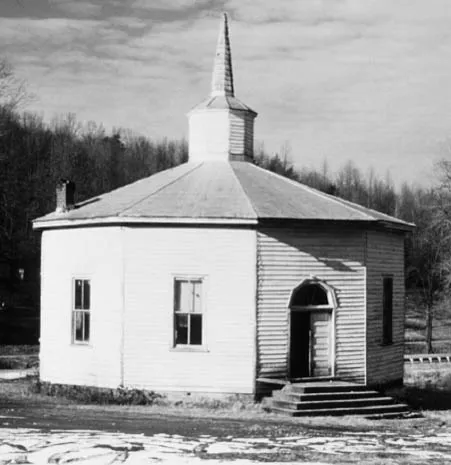

While she wasn’t aware of a nearby cemetery, Mrs. Burton pointed me to her church, Zion Baptist Church, a mile down the road in North Garden, where many of her family members lay at rest. She counted off the relatives buried there: her husband, sister, three uncles, and mother and father. I noticed on her wall a folksy painting of an oddly proportioned church, with many more than four sides. When I commented on it, she revealed that she was the artist. The “ten-cornered church” was the original Zion Church, built in 1871 (fig. 1). Mrs. Burton theorized that the younger members wanted a more modern building. In particular they were not happy with the lack of indoor plumbing for the congregation. So they built a modern, concrete church and, in 1975, tore down the one-hundred-year-old structure. Only later did they find out that it had been recorded in the Historic American Buildings Survey as a rare example of a decahedral American church.5

Today, any number of preservation groups would have jumped to help Mrs. Burton preserve the Zion Church. But in the 1970s, the preservation movement was still an elite, predominantly white group, and African American history was undervalued in federal programs. At the time, the National Register of Historic Places listed homes associated with notable white men. In fact, the entire American preservation movement had started in the nineteenth century, when a group of women banded together to save George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Fortunately, times have changed, and the register has broadened its scope to include historic black schools, old barns, rural cemeteries, and Native American archaeological sites. But it was too late to save the unique and beautiful ten-sided church.

FIG. 1 Original Zion Baptist Church, decahedron-shaped building built in 1871, Albemarle County. Photograph taken shortly before its demolition. (Photograph courtesy of K. Edward Lay, May 1975)

Further destruction of the Zion Church grounds resulted from the enlargement of the nearby rural throughway, Route 29. Mrs. Burton recalled that many gravestones were moved or destroyed during the road expansion. “It was so bad to disturb those old people,” Mrs. Burton lamented. When I arrived at the cemetery, I found a small group of older stones adjacent to the road, while the majority of the stones lay safe, a greater distance away. It’s possible that many burials lie under the current roadway, their markers discarded during the construction.

I was able to guess the age of the cemetery by a quick perusal of the stone types. Among the surviving headstones are those crafted from older materials, such as marble and fieldstones, as well as newer granite markers that did not become popular in America until the late nineteenth century. It was also important to realize what might be missing: the wooden stakes that undoubtedly once marked the numerous depressions. I guessed which floral plantings might have originally been used to mark burials. What stood before me in 2008 suggested that the cemetery had been in use for a century or more. Like many black cemeteries in the South, it was probably founded after emancipation, in parallel with the first free black churches. This guess is supported by records that date the founding of the Zion Baptist Church to 1871.6

In the new portion of the cemetery, I saw a series of orderly rows with evenly spaced markers of all shapes and sizes. I wondered if I would find the deceased family members that Mrs. Burton had mentioned during our visit. I took out my digital camera, a sheet of graph paper, a measuring tape, and a mirror to redirect sunlight onto particularly dark or hard-to-read stones. With my measuring apparatus I created a sketch of the markers, roughly to scale. I often bring a paper spreadsheet to label each stone as I photograph it, recording any available information. With inscribed stones, it’s most efficient to methodically photograph each stone beginning at one end of a row rather than transcribing the information in the field. Later, at home, I transcribe the information from the photographs into an Excel spreadsheet that records two dozen categories of information. This rapid recording method is particularly advantageous during the hot summer months, when ticks take advantage of organisms that stand too long in one place, or on cold winter days when equipment, pens, and surveyors tend to freeze up if you stand still. That day, the temperature was a comfortable sixty degrees, but the good light would only last for another hour, so I moved quickly from stone to stone.

Having spent two decades recording gravestone inscriptions, I immediately noticed that the Zion Church Cemetery contained a high percentage of “love” inscriptions: “In Loving Memory,” “Beloved Husband,” “I Love You—Miss You,” and “Always Loving, Always Loved.” Other inscriptions focused on a subtheme: “Always In Our Hearts” and the variation “Forever In Our Hearts.” A remarkable number, 33 percent of its inscribed stones, used this adage. The “loving” theme was an intriguing deviation from the standard, more prosaic inscriptions such as “In Memory of” and “Rest in Peace.” I made a note to research any possible connection with a nearby “Loving Road”—probably just a coincidence, but you never know.

Beyond the unique inscription variations at the Zion Cemetery, I uncovered many typical structural forms and motifs. Two common styles are the standardized white marble stones provided by the government for veterans and the short metal markers provided by funeral homes. Most graves (70 percent or more) bore plain markers, often carved from marble or granite, with only the name of the deceased and birth and death dates (or, in some cases, a death date and age). But the cemetery also had a surprising number of inscribed and decorated graves: fifty-four stones had some inscription, and seventy-one were decorated with a design, some containing multiple motifs. One was inscribed “Sending Up My Timber,” the title of a popular gospel song of the era.

The congregation selected typical late nineteenth- and twentieth-century motifs: the majority, about 65 percent, expressed religious themes (such as crosses, praying hands, Bibles, and rays of sunlight from heaven), while the remaining designs focused on floral themes (mostly roses and ivy, associated with mourning and immortality, respectively). Each of these motifs was used indiscriminately for men and women, the old and the young. Other motifs are specific to certain identities: an infant is commemorated with a ribbon tied into a bow at the top of the stone or a pair of baby shoes (all inscribed into granite). On another, a carved dove, carrying a piece of ivy in its beak, flies through an elaborate curtain. The stone commemorates Angieline Walker, who died at age thirty-four in 1920. A more contemporary stone, from 2004, is a three-dimensional double heart. Each heart represents half of a married couple, with a ribbon inscribed with the family name connecting the two.

Some church members expressed their aesthetic preferences by combining two otherwise common styles into an unusual stone type. In one example, a carver pasted a metal funeral-home marker in the center of a piece of whitewashed concrete. The metal markers usually stand alone, stuck into the ground on a rod. An even more unusual variant in the Zion Church Cemetery is a concrete stone with small pieces of quartz affixed to the front (fig. ...