![]()

1 } The Brook and the Road

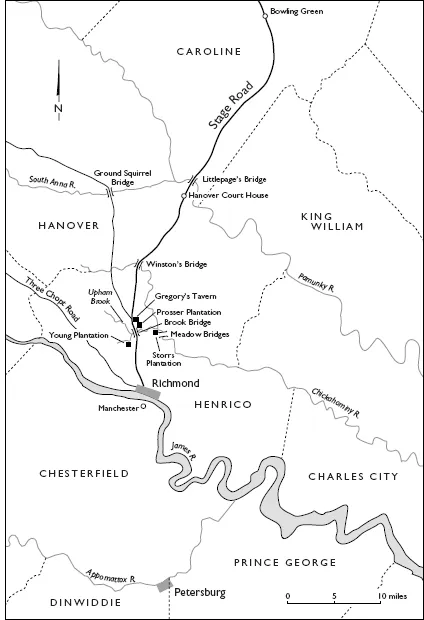

Two geographical features dominate Gabriel’s Conspiracy. One is a waterway known as the Brook. The other is the stage road that crossed it, called Brook Road. In 1800, Brook Road headed north out of Richmond and in about five or six miles reached the Brook, which rose northwest of the capital city of Virginia. Once called variations of Ufnam Brook, and today known as Upham Brook, it generally descended in an easterly direction. It emptied into the Chickahominy River, the northern boundary of Henrico County, not far from the Meadow Bridges, which sat six miles or so north and a little east of the city. The fact that residents of the county simply referred to the area surrounding the creek and its tributaries as “the Brook” suggests its topographical and social importance. White men and women in the neighborhood of the Brook held the majority of the enslaved men accused of the conspiracy. For example, west of the road and before its descent toward the Brook Bridge lay the lands of one of them, William Young, and adjacent to his tracts sat a schoolhouse with a spring, one of many that fed the run. Young was part owner of the schoolhouse lot, perhaps a patron in a state which had only recently begun to provide any support for public education. He also owned a mill in a fork of the Brook above where the road crossed the stream. Among his near neighbors were members of the Williamson and Price families, including Dabney Williamson and Sally Price, and the heirs of Jacob Smith, all individuals who held conspirators. Farther upstream than Young’s lands, the main run of the Brook was nourished by several branches that partly drained the ridge that often bedded Three Chopt Road. This thoroughfare struck out to the west from Richmond, spanned a tributary of Tuckahoe Creek called Deep Run, which gave its name to nearby coal pits, and entered Goochland County just as it crossed Little Tuckahoe Creek. By then, the road was about fifteen miles or so northwest of the capitol. Near Three Chopt Road, but much closer to Young’s and the Brook drainage were the habitations, or quarters, of John Buchanan and John Mayo. Their lands and the slaves who worked them were more a part of the Brook community than the neighborhood surrounding the distant reaches of the sources of Tuckahoe Creek, which drained south into the James River.1

Map 2. The center of conspiracy. (Map by Bill Nelson)

Other residents of the Brook with slaves involved in the plot resided to the east of Young’s land near the stage road and stream. They included Allen Williamson, Thomas and William Burton, Thomas Woodfin, and Izard Bacon. Bacon’s near neighbor, Gervas Storrs, lived farthest downstream, closer to where the Brook emptied into the Chickahominy. Although he had no slaves accused, he had recently been appointed a justice on the Henrico bench, and would play a crucial role in the judicial proceedings against the conspirators. Also included in this part of the neighborhood were some of John Brooke’s tracts and the lands of Drury Wood, which he would soon start subdividing into small parcels, probably because their closer proximity to the Richmond side of the community could more easily capture the opportunities created by the capital’s growth and expansion. These men would each have a slave accused of joining the plot.2

From a crow’s eye, the Brook Bridge appeared to buckle the neighborhood together, the road and the causeway connected to it looking like a belt stretching between Richmond and the Chickahominy. Predominantly on the north side of the stream, but not too far from Young’s, were the lands, mills, and home of Thomas Henry Prosser, the unmarried twenty-three-year-old son and recent heir of Thomas, who had once served as sheriff, coroner, and county justice of Henrico after his permanent expulsion from the House of Burgesses in 1765, when he sat for Cumberland County. He had also inherited Gabriel and other plotters. Close, too, were Nathaniel Wilkinson, a former sheriff and the current ranking justice and county treasurer, and Captain Roger Gregory, whose tracts abutted each other’s and Prosser’s at various points. Before his death in 1798, Thomas Prosser had repaired or rebuilt Brook Bridge at public charge, and had served as the surveyor or road supervisor between it and Winston’s Bridge farther north. The latter structure carried Brook Road over the Chickahominy as it continued as the stage route running through Hanover County, and eventually across Caroline County and on toward Fredericksburg. Prosser’s Tavern sat closer to the Brook, perhaps still located in an old store of Thomas Prosser’s, as it had been in the late 1780s, and apparently run by George Watson in 1800. On the tavern grounds, Gervas Storrs conducted the election in the Brook District for the county’s overseers of the poor that summer, and in an adjacent field, a deputy sheriff would hang five of the conspirators that fall. Farther along the road, about seven or eight miles from Richmond, sat Gregory’s Tavern, a newer establishment where a portion of the local militia’s arms were stored. It was still operated that summer by Thomas Priddy, who had succeeded Thomas Prosser as the supervisor of the section of the road between the two bridges. Gregory, Prosser, and Wilkinson were neighbors with the Mosby, Sheppard, Owen, Allen, and Burton families, among others. Their slaves, some of them conspirators, worked the higher grounds and the often wet lowlands between the Brook and the Chickahominy. In fact, some had the skills to create drainage ditches or kennels that sometimes served as both property boundaries and channels to remove excess water. Flowing from the west into the North Run of the Brook were the Hungary and Rocky Branches, or Creeks, whose outstretched fingertips almost touched the Deep Run coal pits. A Baptist meeting house near the Hungary Branch served this part of the neighborhood as a site of religious gatherings, and while masters and mistresses worshiped and prayed, it unknowingly to them provided slave men with a recruiting ground for the conspiracy.3

Two important roads split or forked from the Brook Road north of the bridge. One headed east to cross the Chickahominy at Wilkinson’s Bridge and provide a convenient route to Hanover County between Winston’s Bridge above and the Meadow Bridges below. Most directly from Winston’s, but also from Wilkinson’s Bridge, roads joined in Hanover County to take the traveler through its narrowest part, past Hanover Court House and on to Littlepage’s Bridge at the Pamunkey River. Over its back, northbound travelers crossed into Caroline County adjacent to the North Wales plantation of absentee Charles Carter and just downstream from South Wales, his quarter in Hanover, homes to plotters. About six or seven miles farther north, the road passed a tavern at White Chimneys, and another fourteen or fifteen miles brought one to Bowling Green, the site of the Caroline County courthouse. Several of the conspirators would be incarcerated and tried there, recruits who lived and worked close to Littlepage’s Bridge and nearer to the Henrico neighborhood of the Brook than to the Caroline County seat.4

The second tangent to the road soon emerged beyond Gregory’s Tavern. But this road angled west and bridged the North Run of the Brook above the mouth of the Hungary Branch. It also crossed the curving Chickahominy, apparently near a now almost forgotten Michams Lick, to enter Hanover. It connected Richmond and Henrico to Louisa and other Central Piedmont counties via the Ground Squirrel Bridge over the South Anna River several miles into Hanover. This bridge was thought to fall within the perimeter of the conspiracy in southwestern Hanover. All these roads and bridges, mostly built and maintained by the black male slaves residing near them, served as important conduits and links, and sometimes as meeting places, for the plotters. The conspiracy, however, emerged and centered in the neighborhood of the Brook among the black men who were held or hired there.5

In 1787 Henrico officials had divided the county for tax purposes, using the road that ran from Richmond to the Meadow Bridges as the district boundary. Their decision placed the neighborhood of the Brook in the western, or upper, segment of the county. In 1800 the tax commissioner returned an upper-district list of some 451 free tithables, or men above the age of sixteen. Not all were white, for among them were at least sixteen free men of color. His tax tally also counted, but did not name, 1,105 black tithables, or enslaved men and women aged sixteen and older, most owned but some hired by the planters, farmers, and the few coal mine operators of the district. An additional 177 enslaved children between twelve and sixteen years old also worked in the upper part of Henrico, the commissioner noting their existence to enrich the state’s coffers, as the law prescribed.6

The slaves who resided in the neighborhood of the Brook produced wheat, corn, some tobacco, and hay. They raised cattle, plowed and carted products to market with horses and mules, and butchered the often free-ranging hogs, once in a while without permission. Millers ground the grain into meal and flour and sawed logs into timber, while others smithed and coopered, ditched and fenced, weeded and hoed, chopped wood, tended the livestock, ran errands, and worked their own garden plots. They also served the families that held them in bondage, doing the domestic drudgery of cooking and waiting, washing and cleaning, and nursing and caring for young children. They raised their own families, too. Late on Saturdays, after their work and if permitted, some men trekked to Richmond or to other plantations, some beyond the boundaries of Henrico, to rejoin family and acquaintances—their “connections,” in the language of the day. Others slipped away without permission, sometimes equipped with fraudulent passes of their own or of someone else’s drafting. Some women had to await the arrival of their husbands from other plantations or from Richmond, Manchester, or places where they might be hired or held. On Sundays, if not at the call of the master or mistress, these slaves might gather to worship, to bury their dead, to gossip, to play quoits or cards, to fish, and even to feast on the fish when the run was on. In the summer of 1800, a few of the men of the Brook moved about these gatherings recruiting other men for the conspiracy.7

They knew each other as they knew their masters. Within their neighborhoods, they recognized who belonged, who could be trusted, who was strong, who was defiant, or who was a stranger, or unreliable, or weak. They also grew up and lived in a mature slave society and understood slavery—it was what it was—but understanding was not acquiescence. And they sometimes glimpsed the power of the state that framed their enslavement, its abilities to communicate and to mobilize its militia, and its authority to prosecute slave crimes in its county courts of oyer and terminer. Presided over by justices who dispensed justice without juries, their decisions capable of inflicting the death penalty for some felonies, they were a mark of Virginia’s slave system. Another, not unique to the state, were the slave patrols pulled from the militia. While not a constant presence, the irregularity of their monthly riding made them more effective, and perceived unrest sent them into the night with greater frequency, always at taxpayer expense. Moreover, every person, white or black, if physically able, could take up a suspected runaway or inform a master or authorities of suspicious activities. But most often, slaves felt the threat or cut of the master’s whip and his power to sell the recalcitrant, the latter made more effective by the bonds of family and affection that had spread and deepened over time. Even the possibility of becoming free, which had become legally much easier in the aftermath of the Revolution, and which had been most heavily used by the Society of Friends, many Methodists, and some Baptists, Episcopalians, and enlightened rationalists, contributed to a master’s power and the shaping of a slave society that functioned sufficiently well to encourage most white Virginians to keep it and to seldom question it except in the abstract. Even so, their system did not leave whites at ease, sheltered in a fantasy that they had nothing to fear. They could see it could not prevent the existence of an underground economy of runaway labor and purloined goods, which many whites believed the growing numbers of free blacks, and even some whites, exploited. Nor could it prevent the grimaces of frustration and the angry mutterings about imagined blows for freedom, protection of loved ones, and in some cases, revenge and retaliation, that were sometimes overheard, if infrequently undertaken. The whisperers may have been quietly noted, too, creating mental lists or points of conversation of “the usual suspects.” In the late spring of 1800, a group of men decided to act, not just conspire, to transform their whispers into a direct attack on Richmond and their enslavement.8

Virginia’s slave society was more mature than the state’s political system and that of the new nation. The state existed under the Constitution of 1776, which instituted a dominant legislative branch composed of an annually elected House of Delegates and Senate. The governor, in 1800 James Monroe, was annually chosen by these two houses of the General Assembly, and was advised by a Council of State, whose eight members were also elected by the House and Senate. Indeed, so were the members of the state judiciary, though not the county justices. The justices remained a self-perpetuating body, where vacancies were filled by appointment of the executive on the justices’ own recommendation. They proved to be a major exception to the Revolutionary-era republicanism that pervaded the Constitution of 1776. But transforming any ideology into institutions that effectively functioned and governed was a challenge. The journals of the Council of State during the 1790s, for example, reveal how specific events provoked discussions of the extent or limits of powers and responsibilities of the offices and branches of government. Since there was no provision for amendments, no real institutional change could occur without adopting a new constitution, so statutes refined and clarified the responsibilities of the government’s branches. And, of course, the Constitution of the United States was even younger, with significant issues of federalism and civil liberty remaining untested or unresolved. Many of these issues emerged in the unfolding crises created in American relations with the two dominant European powers, England and France. The first sustained and truly contested presidential election, in 1800, encapsulated and exposed many of the divisive issues confronting the nation. Indeed, while the slave conspirators put together their plan, white Virginians followed an increasingly bitter presidential political campaign which sometimes was portrayed in conspiratorial images. Early in 1800, in a tactic calculated to deliver all of Virginia’s electoral votes to favorite son Thomas Jefferson, Republicans in the Virginia General Assembly had succeeded in passing a measure that established a statewide election for presidential electors, rather than choosing electors on a district basis, which had been the case in 1796. As the spring wore on, elections in other states made a Republican victory seem more likely, leading the Federalists to raise their rhetoric of fear about a Jefferson election. Any advantage John Adams might have gained from his incumbency was finally destroyed when the Federalists themselves split along the fault of Alexander Hamilton’s ultimate and openly expressed opposition to Adams’s reelection. For arch-Federalists like Hamilton, and those of the Federalist press who found it useful to brand Jefferson a Jacobin, Adams had gone soft on France. His effort to reestablish peaceful relations with the European power was unbelievable and unpardonable. If nothing else, it undercut the rationale for the Federalist-inspired expansion of the nation’s military forces and their rationalization for wartime restrictions on political opposition. Still, there was a chance that the Federalists might retain the presidency through the election of either Adams or Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina, so the contest continued to generate considerable heat. Richmond, the home of John Marshall, by sending Federalist Charles Cop land as its representative to the General Assembly in 1800, appeared to be a Federalist island in the midst of true republicanism. William Rind provided the Federalists with a voice through the Virginia Federalist, but left late that summer to found a Federalist paper in Georgetown, close to the new national capital. Consequently, residents of Richmond and Henrico were more likely to see columns that ran the political spectrum, from Richmond postmaster Augustine Davis’s Virginia Gazette, through Samuel Pleasants Jr.’s Virginia Argus, to the most aggressively Republican paper, Meriwether Jones’s Richmond Examiner. The latter especially attacked the Federalists through the venomous pen of James Thomson Callender, a refugee from the newspaper wars in Philadelphia.9

In 1798, in anticipation of war and hoping to eliminate a political opposition many in the country had not yet learned to accommodate, the Federalist-controlled Congress had passed a series of punitive measures, including the Sedition Act, which criminalized criticism of the government. In the early summer of 1800, the presidential campaign and the Sedition Act collided in the federal court of Richmond. In a case presided over by Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, the government tried James Thomson Callender, who had proved one of John Adams’s harshest critics. After fleeing beatings and threats in Philadelphia, he had lambasted the Adams administration in his The Prospect Before Us, printed on the Richmond presses of Meriwether Jones, Samuel Pleasants Jr., and another displaced Republican printer named James Lyon. The prospect of the upcoming trial created much tension and attracted a lot of attention, although John Minor believed it would do Callender “more good than harm, [for] it will enable him to sell off his Books which otherwise he would not have been able to do.” With the outbreak of the Quasi-War with France, Congress had also expanded the United States armed forces. Subsequently, a regiment of about four hundred men under the command of a Virginian, Col. William Bentley, had taken up station several months before near Warwick, four miles downstream of Richmond in Chesterfield County. It was believed they were to move on to Harpers Ferry in the spring, but they remained near the capital. In the heated political atmosphere of 1800, with the lingering old republican fears of a standing army as a sure sign of intended oppression, the encampment of the regiment raised concerns. As early as December 1799, St. George Tucker had expressed his worries over the troops near the capital, fearing that they were meant to be dispatched to courthouses to influence the election. On 15 May, Vir...