![]()

1 Mountain Neighbors

TWO COMMUNITIES ON THE FRONTIER OF THE ANTEBELLUM SOUTH

Perhaps no region of the United States has been so misunderstood and misrepresented as the Southern mountain lands known collectively as Appalachia. When Americans think of Appalachia, they often believe it to be a distinct region with identifiable characteristics. Fed by media depictions and the writings of some “experts,” our society has constructed a cultural stereotype of a people and a region. The characteristics of this stereotype are obvious to most readers: Appalachia is poor, backward, isolated, wild, rugged, mysterious, unique. And, above all, Appalachia is basically the same all over. Scholars have made some similar assumptions and have argued over the years that Appalachia possessed a kind of regional integrity, a series of social, economic, and political features that permeated the entire mountain area of Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia. In the last twenty years, however, newer scholarship has applied the deconstructing techniques of community study to Appalachia. The resulting portrait is a variegated, locally unique Appalachia, a mosaic that explains rather than ignores local differences.

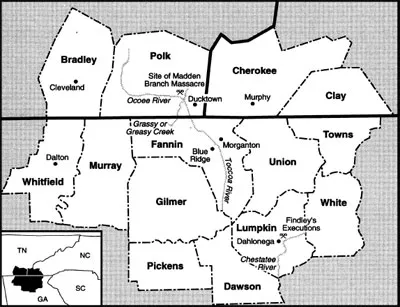

Lumpkin County and Fannin County are two north Georgia counties that lie astride the Blue Ridge Mountains. Both were founded in the three decades before the Civil War. They share a common border and a common geography. During the Civil War, the residents of both counties endured divided loyalties and internal strife. But despite these similarities, the two counties responded differently to the war because of different histories, economic foundations, and demographic realities. Their story illustrates how complex differences exist even within this supposedly monolithic region of America.

The images are familiarly American—crude, lawless boomtowns; a spectacular and dangerous wilderness; Native American tribespeople; hardscrabble prospectors and settlers. But although these descriptions might seem conjured from America’s mythic Wild West, they also depict a vital period in antebellum Southern history, a period in which the nascent forces of development began their assault on one of the last of the South’s frontiers. Beginning in the late 1820s, the state of Georgia extended full sovereignty over its mountainous northern section, previously linked only tenuously with the rest of the state. Pursuing mineral wealth, land, and independence, white Georgians swarmed into the Blue Ridge country, ultimately expelling the indigenous Cherokee peoples and starting the integration of this peripheral section into the regional and national mainstream. The catalyst for this invasion was the first genuine gold rush in American history, resulting in a rapid and uncontrolled demographic explosion that had profound consequences for the future of the region. Although most of the “twenty-niners” in this initial wave of settlement abandoned north Georgia after the gold ran out in the 1840s, those who remained lived with the legacy of this frontier period for decades to come. The antebellum history of the region saw the development of rival visions of society, one developed, ordered, commercial, the other chaotic, lawless, and violent. This dual heritage had profound consequences for north Georgia’s experience during the Civil War.

Map of the north Georgia border counties. (Courtesy Georgia Historical Society)

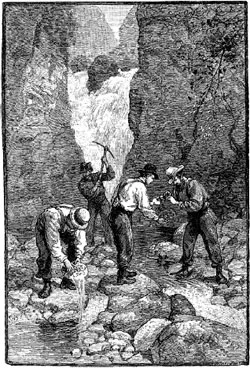

Prospectors may have discovered gold in what would become Lumpkin County as early as 1828. By the summer of the following year, newspapers were proclaiming that the region still known as Cherokee Georgia was full of “the hidden treasures of the earth.”1 Over the next several months, thousands of miners infiltrated what was still legally Indian territory, leaving the state of Georgia, the president of the United States, and John Marshall’s Supreme Court to debate the constitutional ramifications. In 1830, the Georgia legislature ratified the miners’ trespass by formally extending the state’s jurisdiction over the disputed northern territory. When, in 1832, Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the U.S. Supreme Court’s decree of Cherokee autonomy, the fate of the region’s Native people was sealed. Within five years, the federal government completed the expulsion of Georgia’s Indians.2

Gold miners scouring a stream in Lumpkin County. The gold boom of the 1830s put Lumpkin County on the map and would later lead to the founding of a branch U.S. mint in Dahlonega. (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, September 1879, p. 519, courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America Digital Collection)

Gold fever spread throughout north Georgia, from the Etowah River in the west to the Chattahoochee River in the east. The heart of the mining region lay along the banks of the Chestatee River, between Gainesville and the southern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains, in what became Lumpkin County. Some of the region’s most productive mines were here, including one owned by states’ rights advocate John C. Calhoun. Auraria, a village lying between the Etowah and Chestatee, became a locus of the mining industry in the spring of 1832. Within a year of its founding, Auraria grew from a single trading post to a thriving town of a thousand people, “100 dwellings, 18 or 20 stores, 12 or 15 law offices, and 4 or 5 taverns.” An astonished observer wrote that “an election was held in a county where a year before there was none but the Indian population. Now, ‘Intruders,’ as the Indians called us, cast 1,800 votes for county offices.” When the Georgia Legislature formally created Lumpkin County in December 1832, they named Auraria its seat. The new county, one of the smallest in area in Georgia, bustled with 10,000 people by 1833.3

This was the formative event of Lumpkin County history. The Cherokee presence and the gold rush experience profoundly shaped the development of north Georgia society, politics, and culture. The influx of miners began an exuberant, if attenuated, drive toward economic development and integration. The resulting chaos of the frontier period would also generate a negative historical stereotype for future residents to overcome. And the interaction with the Cherokee taught north Georgians to treat enemies with ruthlessness and even savagery. The experience gained in “othering” the Native peoples would resurface later during another period of social flux—the Civil War.

Lumpkin County in the 1830s was a frontier in every sense of the word. Rugged terrain, crossed only at intervals by muddy roads, isolated the mining communities from each other and from the rest of the state. One of the original miners recalled that “living was precarious. All the supplies had to be carried by wagon … across the mountains, and the necessities of life were expensive, while the luxuries were unknown.” On the periphery of civilization, some of the new immigrants paid little heed to the rules and conventions of respectable society. “The miners were a rough and ready set,” admitted one observer, who lived in “bark shanties which were regarded as common property and might be appropriated by any miner who might be temporarily located in any portion of the country.”4 Indeed, to some outsiders it appeared that the miners reveled in their defiance of societal norms and institutions. Garrett Andrews, a visiting attorney, recounted with amusement that established religion seemed an especially unwelcome trapping of civilization in the mountains. Andrews noted that the miners spent their leisure hours gathered in their hovels, “drinking and gambling,” ignoring the imputations of a certain “preacher from the interior of Georgia … [who] went to one of these sinks of iniquity for the purpose of rebuking the sins of that place.” As Andrews recollected, the miners promptly laughed their would-be deliverer out of camp. Other missionaries were not as devoted, and several who came to rescue the miners from “the drunken hells and gambling holes” abandoned their charges and were “found in the gold pits rather than in the work of reformation.”5

The boisterous lifestyle often offended established sexual norms and gender roles, as women took on “masculine” characteristics in the rough-and-tumble mining camps. To be sure, elite women served in conventional semipublic roles. Agnes Paschal managed an Auraria hotel and also helped nurse the residents of the town through an outbreak of fever in the summer of 1833. She earned a local reputation as a “ministering angel” for her efforts. But other mountain women clearly lived outside the bounds of conventional society. Women were “as vile and wicked” as men, wrote one middle-class resident of Lumpkin County, and “gambling houses, dancing houses, drinking saloons, houses of ill-fame, billiard saloons, and tenpin alleys were open day and night.” Miner Edward Isham had paramours and common-law wives of both races who seemed to drift in and out of sexual relationships as easily as he did. One miner recalled that “sometimes both sexes engaged in … fisticuff fights by the hundreds” that often raged in the mining camps. Other women worked in the mines and taverns, despite the derision of male miners. A lawyer from lower Georgia, riding the mountain circuit in the 1830s, noted the unrestrained and decidedly unfeminine behavior of local females brought before the bar on such charges as assault and battery. During one trial, a woman defendant, a “wiry and sinewy girl in her twenties,” admitted to beating another woman with a piece of wood, exclaiming “that she was little in body, but mighty big in spirit, that she was as supple as a lumberjack, strong as a jack-screw, and savage as a wild-cat!”6 Qualities attributed to frontier men thus applied to some women as well.

Lumpkin County was born in violence and lawlessness, and these characteristics were elemental components of north Georgia’s frontier culture. The invasion of north Georgia that followed the discovery of gold was in effect a gigantic violation of the federal law protecting these lands for the Cherokee. From the outset, miners diligently evaded restrictions on their activities, ignoring federal decrees and hiding from U.S. troops sent to expel trespassers in 1830. Miners showed few compunctions about using violence to defend their interests, something that Colonel John W. A. Sanders discovered when his troops arrested several white intruders in Lumpkin County in the winter of 1831. As the troops led their prisoners out of the mountains, dozens of miners gathered in ambush, felling trees in the troops’ path and attacking the rear guard as they attempted to cross the Chestatee River at Leather’s Ford. The commanding officer reported that the miners “continued the assault with great fury, until checked with the bayonet.”7

If miners were eager to fight the authorities to defend their gold claims, they were often equally content to fight each other. Though murder was rare even in the early days, assault, mayhem, and other violent crimes were rife. The autobiography of Edward Isham, who mined in north Georgia in 1840 and 1850s, is largely a litany of scuffles with other mountaineers, in which the quick-tempered miner boasted of committing numerous stabbings, shootings, and beatings. In addition to the commonplace individual battles, scores of miners sometimes filled the streets of Auraria and Dahlonega in massive brawls, “swearing, striking, and gouging, as frontier men only can do these things,” as one observer complained. One miner recollected cavalierly “that only a dozen or so … battles occurred, in which clubs, rocks, picks and knives were freely used and a few dozen heads broken and several men’s bread sacks cut out.” Auraria’s public officials decried the lack of a regular police force to quell such violence, but police could have done little to stop such huge scuffles, some of which involved almost a hundred men. As in other frontier communities from Texas to California, north Georgians sometimes resorted to vigilante justice to restore order. Men who broke the miner’s code were whipped, branded, or ridden on a rail. Later, after county government became more established, Lumpkin residents were content to give the regular justice system a reasonable chance to keep order before resorting to extralegal means.8

Much of the violence in the gold region involved the Cherokee directly or indirectly. The Cherokee had ceased organized warfare against whites by time of the gold rush. Intermarriage with whites was common, and a Cherokee elite pursued a lifestyle virtually indistinguishable from Southern middle-class planters. Despite this, white Georgians who flocked into the mountains brought with them the stereotype of the demonic red savage, eager to shed the blood of white men, women, and children. Local papers carried frequent alarms of real or rumored Indian atrocities, reports that frightened those ready to believe in the inherent ruthlessness of Native Americans. In the spring of 1833, the Auraria Western Herald used barbaric imagery to report a harrowing battle between Indians and whites in which “25 or 30 Indians, all painted and undressed, rushed out and attacked” a group of white miners “with sticks, clubs and rocks.” Hand-to-hand combat raged for hours, with the miners fighting back with picks, shovels, and mining tools.9

In fact, although such clashes did occur, whites were more often the aggressors. Miners showed little regard for Indians’ claims of ancestral rights and from the beginning of the gold rush violated them with impunity. Groups of white outlaws calling themselves “pony clubs” roamed north Georgia during the early 1830s, terrorizing Indian families, stealing livestock, and occasionally murdering those who resisted. Cherokee leaders protested. “Our neighbors who regard no law and pay no respects to the laws of humanity are now reaping a plentiful harvest,” the editors of the Cherokee Phoenix charged in 1829. “These neighbors … take the cattle belonging to the Cherokees. The Cherokees go in pursuit of their property, but all they can effect is to see their cattle snugly kept in the lots of the robbers” (Georgia law forbade Indians from pursuing such claims in state courts). This violence culminated in 1838, when President Martin Van Buren ordered U.S. troops to north Georgia to expel the Cherokee from their property. North Georgia militia and civilians joined in the exercise, often looting and burning Indian homes in the wake of the evictions. When some Indians resisted by force, mountaineers called for brutal retaliation, demanding that any white casualties be repaid with three times as many Cherokee deaths. Local whites who did not participate in the removal nevertheless took satisfaction in the event. While thousands of Indians were dying on the Trail of Tears, the Lumpkin County Grand Jury expressed “unmixed pride and pleasure” at the swift progress of the expulsion.10

In Lumpkin County, therefore, geographical isolation and a lack of strong institutions created a relatively unstructured society. For many twenty-niners, life in the Georgia mountains was chaotic, violent, unrestricted, and individualistic. Indeed, these are the qualities that chroniclers of Appalachia have long attributed to the region as a whole. Beginning in the 1870s, local color writers, missionaries, politicians, and sociologists portrayed Appalachia as a primitive and unchanging land of clannish, unenlightened, and anachronistic communities. Outsiders either castigated or pitied mountaineers as backward barbarians who were beyond the reach of broader societal values or morals—people whom time forgot. It is important to note that historians of Appalachia have sought to debunk this interpretation since the 1970s. Recent scholars who seek to dispel these stereotypes find support in the case of north Georgia. For although some elements of the Appalachian stereotype undoubtedly applied to north Georgia society in the 1830s, countervailing cultural trends developed. The frontier culture of early Lumpkin County always coexisted with a different set of values, values devoted to development, a market economy, institutions, and social order.11

Even at the height of the gold rush, when thousands of transients flooded the mountains seeking only to get rich, some in Lumpkin County had their eye on the long term. These people focused their energies on transforming the wilderness into solid communities with ties to the rest of the state, region, and nation. Agnes Paschal, who immigrated to Auraria from lower Georgia with her son in 1833, was an example of this spirit. Offended by the lack of organized religion in the mining camps, Paschal led an effort to build the first Baptist church in Lumpkin County. Others followed her lead, and by the end of the decade Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches had sprung up throughout the county. The new churches enforced middle-class, Christian values upon the frontier. Congregations tried members for moral offenses such as drunkenness, whipped up mobs of men and boys to remove “vile, lewd women,” and took the lead in forming temperance societies, which were quite numerous by the 1840s. When one enterprising miner tried to open a saloon on the grounds of the county court house, a polite mob of temperance men told the proprietors that “if the groggery was put up they would tear it down.” The bar never opened.12

As the county grew more established, it attracted an increasing number of persons seeking long-term settlement. During the early to mid-1830s, Lumpkin’s “founding families” arrived and began the process of “civilizing” the region that would characterize the post–gold rush decades. Archibald G. Wimpy arrived in Dahlonega in 1837 and established a small dry-goods store. Success followed, and Wimpy soon expanded into mill operations and plantation agriculture. He became the largest slaveholder in the county and was one of the wealthiest and best-known residents of the county by the time of the Civil War. Weir Boyd emigrated to Lumpkin as a teenager with his parents in 1835. When Boyd grew to manhood he became a successful attorney and local politician, served several terms in the state ...