![]()

1

A SOCIAL ART

A central characteristic of architecture as environmental design was its dual allegiance: to political and public action, on the one hand, and to scientific inquiry and knowledge, on the other. These two ideas, and the contradictions between them, shaped both the term and its fate in architectural discourse. This chapter examines how and why these ideas were conflated in the 1930s and describes the implications of applying a pragmatist philosophy to architecture. The chapter then examines the first shift in the history of architecture as environmental design: the move from the context of the New Deal and the challenges of war to the institution-building era of the postwar years. With a majority of the profession caught up in the building boom and housing efforts curtailed by federal policy, the proponents of an environmental approach to architecture turned away from public projects to professional education and institution building. The pragmatist ideas were accordingly transmuted into an emphasis on collaboration between architects and planners, along with the incorporation of scientific knowledge in architectural design and the development of research for architecture that would support a “broadening of the base” of the profession. These ideas allowed architecture educators to expand architecture education in the growing research universities and to create institutional centers for the continued exploration of environmental design.

The Architect in New Fields

The idea of architecture as environmental design emerged during the Depression Era, developed primarily by architects who were stimulated by the collaborative and practical work they undertook with New Deal agencies. Working for the federal agencies, architects encountered a new set of “clients” and needs, all while collaborating closely with planners, landscape architects, economists, and other experts, a collaboration that opened the door to new fields and new professional responsibilities. Many of the recruits espoused the New Deal’s social and political rhetoric and developed a strong commitment to working “for the people.” As architectural historian Talbot Hamlin reported in 1933, architects began to realize that their work was deeply impacted by “the great dilemmas of poverty and wealth.”1 Among these impassioned architects were those who were confident that they were witnessing a new social order that would require a fundamental adjustment of their practice. They began to theorize their work even as they were still engaged in it, expressing their political fervor in terms specific to their profession. In the process, they took the theoretical positions about the importance of “housing” and applied them to architecture in general.

The term environment captured two of these ideas. First, it widened the purview of architects to include all aspects of the human world, including topics such as housing and large-scale planning, which had previously been considered beyond the scope of the profession. Conveniently, environment could be (and was) applied to both natural and rural areas and to cities. Secondly, the idea of the environment captured the notion that architecture was shaped, not through fine art, but in the balance between humans and their surroundings. A second term, research, represented the pragmatic/progressive commitment to scientific knowledge and to social experiments and the specific elements of people and place over rational, universalist solutions.

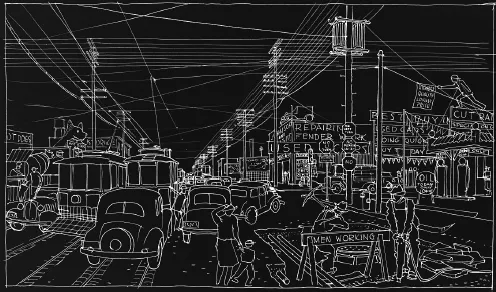

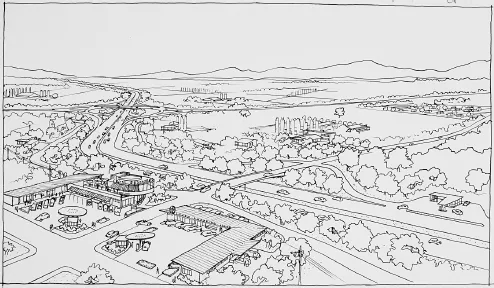

The discourse among members of a San Francisco Bay Area advocacy group, Telesis, illustrates the conflation of these terms. The group was formed in 1939, and the early suggestions for naming it all included the term environment, such as Designers of the New Environment; or Forum for the Study of the New Environment; or Contemporary Environmental Forum.2 In 1939 the group staged an exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Art titled “Space for Living,” in which they portrayed the possibilities of modern planning and proposed the region as a unit for environmental analysis (figs. 2 and 3). The exhibit was designed to dramatize the difference between existing conditions and the large-scale reorganization the group envisioned. Thousands visited the display, including Catherine Bauer, who was a lecturer in the Department of Social Welfare at the University of California, Berkeley, where she taught a course on housing.3

Figure 2. Sketch by Vernon DeMars for an exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1939. This sketch depicts “living as is,” which was juxtaposed with “living as it should be,” shown in fig. 3. (Telesis exhibition sketches, Vernon DeMars Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley)

Bauer was also a member of the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA), to which the Telesis members looked for inspiration. This group, established by Lewis Mumford in 1926, envisioned regional utopias. Mumford applied an idea propounded by the Scottish biologist Patrick Geddes to the American context. Geddes argued that the logic of biological systems could be adapted to understand and improve social systems. For Geddes, the role of town planning, which he called “folk-planning,” was a process of identifying and augmenting environments for people in which they could flourish. He expected different types of people (whom he defined by their occupations) to thrive in different environments, as he illustrated in his well-known valley section. Geddes argued that the process of creating such environments began with a detailed appreciation of the “spirit of the place.” He expected this appreciation to develop from a systematic—or “scientific,” in the usage of the day—survey of existing conditions. This survey method was based in what he called a “Notation of Life,” a system for expressing order in complex systems.4 It relied on classification, the fragmentation of the world into small, solvable parts. Building on such detailed surveys, Geddes envisioned the return of “beauty,” by which he meant a balance in nature that will support permanent human wealth, expressed in art and architecture. Thus, for him artists and architects were the natural leaders of the new order.5

Figure 3. Sketch by Vernon DeMars for the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1939. This sketch shows “living as it should be,” demonstrating the Telesis group’s belief in large-scale city and regional planning. (Telesis exhibition sketches, Vernon DeMars Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley)

Geddes’s new order was dependent on a unity between city and country, or what he calls a region. The notion of the region was at the heart of the RPAA discussions and was most fully developed in Mumford’s 1938 book, The Culture of Cities.6 In this book he outlined a history of Western cities up to the “rise and fall of the megapolis” and advocated a fourth, and final, American “migration” toward building a balanced regional environment in which people could live decent and healthy lives in small towns, relying on technology for continued productivity.7 The regional vision he espoused was a social system writ large on the landscape. For Mumford and his colleagues, the unified region, united with a comprehensive plan for housing, was the basis for a true democratic future.

Telesis members also celebrated Bauer’s 1934 book, Modern Housing.8 It was a clear and concise exposition of European public housing projects that challenged the United States to aspire to a similar level of public responsibility, offering suggested ways to meet this challenge.9 In this book, written for an American audience, Bauer advocated a progressive notion of social reform, which, she explained, was neither socialism nor rampant speculation but a creative and productive middle ground where public discourse is balanced between these two extremes. Bauer was an unlikely houser (the term used to describe those involved in housing reform). A graduate of Vassar College, where she studied English, Bauer had also completed several courses in architecture at Cornell University; her initial interest in architecture was that of an aesthete attracted to new and modern forms. This interest took her to Europe in 1926, where she was impressed by the work of Ernest May in Frankfurt, Germany, and specifically by its social dimensions. Four years later, when she returned to Europe (with Mumford) for a research trip, she participated in a course on The New Construction organized by May, and she attended lectures by Richard Neutra and others.

Bauer’s association with the RPAA provided a counterbalance to the technological emphasis she had absorbed in Europe. Here she met Dr. Edith Elmer Wood, whose 1919 book, Housing of the Unskilled Wage Earner, discussed housing in the context of a laissez-faire economy and argued that the effective market for new private housing was limited to the wealthiest third of the American population.10 Bauer would later call this “a remarkable guess, as all the exhaustive field research of the past ten years has merely served to confirm it.”11 In the 1930s, Bauer also threw herself into political action, and she was instrumental in the congressional lobbying that eventually resulted in the first Housing Act of 1937. The bill, which Bauer helped write, introduced a public housing program, formalizing the Progressive reform efforts of the previous decades.12 The long-term effects of public housing programs have been hotly debated, but the government’s assumption of responsibility for housing impacted the profession, providing architects with welcome new opportunities to exercise their meager professional power. Even the conservative American Institute of Architects (AIA) endorsed public housing in 1936 and would do so again in 1941.13

Mumford and Bauer, together with RPAA colleagues Henry Wright and Clarence Stein, presented their ideas at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City as part of the seminal exhibit on modern architecture in 1932. Here their ideas were juxtaposed with what came to be known as the International Style. The main part of the exhibit was curated by historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock and connoisseur (later architect) Phillip Johnson and supported by museum director Alfred Barr. Composed of photographs and models of buildings, this main section was designed to introduce a “cohesive modern style” to American architecture based on designs from Europe. That formal presentation tore the Modernist idiom from its political and social aspirations and foregrounded its aesthetic dimensions. The RPAA display, while it also included images of housing projects and regional plans, relied as much on written as on visual persuasion. This fundamental difference would play an important role in the fate of each of the ideas after the war.

Bauer also drew on Geddes’s ideas, particularly his call for social collaboration or “simultaneous action,” which he saw as an antidote to the class struggle described by Marx. Bauer argued that all the humans who were in a relationship with an environment should participate in shaping it and work together toward common goals: “it is everyone’s business.”14 Bauer’s “active participants” were the educated and motivated citizens of a democracy, not the downtrodden masses. This notion of a public was later challenged as narrow and racist, but it was foundational to the pragmatist and progressive worldview. Bauer recognized that such simultaneous action often led to contentious debate and even to conflict, but she welcomed these as the signs of a successful and meaningful process. She called on experts to coordinate and lead these discussions, or more specifically to pose alternatives for the public, so that the ultimate users of a project could make an informed decision. In this emphasis on method over content, or practice over form, experts were not those who knew best but rather those who could best use both existing and novel methods to support public debate. This was in contrast to the powerful “culture of expertise” that celebrated the objective knowledge of the professional. Bauer worried that “it is a sign of professional weakness if the architect or planner comes out of his drafting room to face the public without having first determined exactly what would be good for them.”15

Geddes’s location of rational action as a step along the way to balance and beauty was also a hallmark of John Dewey’s philosophy. For Dewey the distinctions between aesthetic experiences, on the one hand, and theoretical, technical, and moral experiences (a distinction that was developed primarily by Kant) are artificial. His description of aesthetic experience is “environmental”—he defines it as a continual process of organism-environment interactions, which include the mind, body, subject, and object. Mark Johnson summarizes what Dewey includes in this: “form and structure, qualities that define a situation, our felt sense of the meaning of things, our rhythmic engagement with our surroundings, and our emotional transactions with other people and our world.”16 Dewey was convinced that every such experience has a “pervasive unifying quality” and that it is the role of philosophy and reflection to recognize and reconstruct this quality. For Dewey, the tendency to differentiate and discriminate between different parts of experiences was a natural part of our biological makeup, and recognizing the unity was a sign of the spiritual components of our humanity.

Dewey described the process of making sense of an experience in the book How We Think (1910).17 He describes five steps (later renamed “phases”), which began with the identification of a “problem.” This step could emerge either from rational observation or from the emotional recognition of an uncomfortable break in experience (or both). The second and third phases consist of rational reflection: the development of a hypothesis to explain the break and testing this hypothesis through e...