![]()

1

At the beginning of Mass one holy day in March 1552, the villagers of Cardenete watched in amazement as Bartolomé Sánchez, tense and irritable, entered the parish church and walked to the front of the main altar. The fifty-one-year-old Sánchez carried a pilgrim’s staff and a red bonnet, the latter decorated with the scallop shells of St. James. In the manner of a penitent, Sánchez also bore some saddlebags weighted down with five stones in expiation of Christ’s five wounds. Further, he had wound a rope around his torso, and, most bizarrely to those who watched the unfolding scene, he limped along on just one shoe. Juan Caballero asked Sánchez why he went with one shoe on and the other off, and received the enigmatic reply that the world was turning topsy-turvy.1

Sánchez knelt before the altar to hear Mass, but at the elevation of the Host the pilgrim closed his eyes so he would not see the supposed miracle of Christ’s presence there. This insult to the sacrament prompted several men to speak to Sánchez, who, still on his knees, rebuffed them: “Leave me alone—don’t talk to me!” An incoherent torrent of invective came tumbling out: “Sátanas and Barrabas! Oh, cursèd Lucifer! St. Francis faith and St. Peter rock! Anyone here want to debate with me? I will not shut up!”2 Miguel Caballero and some others took him outside the church, where Sánchez’s cousin Bartolomé de Mora heard him declare that he had carried the pilgrim’s staff all the way to Santiago de Compostela, five hundred miles away. He dared not contradict him.3

2. Parish church of Cardenete. (Photograph by the author)

No one in Cardenete knew why Sánchez had donned the pilgrim’s garb, or for that matter why he seemed so agitated. Before his blasphemous behavior in church, there had been a minor public incident or two, but nothing really to attract attention. Most people in the village knew only that since 1551 Sánchez had worked side by side with Juan García Masegoso carding wool for various neighbors, and to supplement his income he occasionally left with other men from the village to work as a migrant farm laborer in La Mancha, sometimes staying away for as long as three months. Once Sánchez had been a farmer himself, but he had not been able to make a living at it and had learned the craft of wool combing.4 He was a good worker and a family man; if he was upset by his descent in the world, he kept his regrets to himself.

2

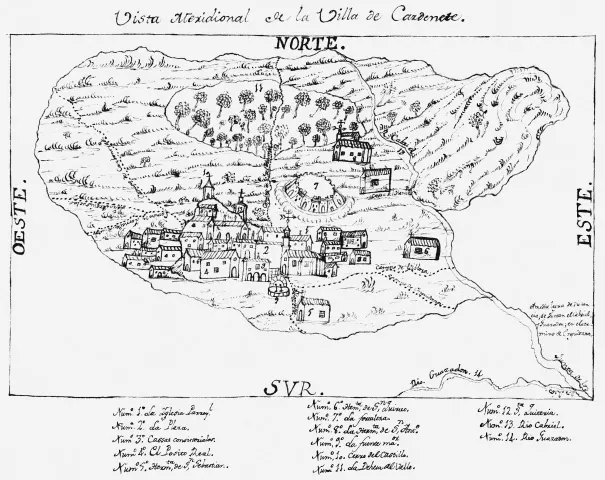

The village of Cardenete, where Sánchez had been born at the beginning of the century, was a settlement like so many others in New Castile: a clutch of whitewashed and red-tiled houses built around a central square, a parish church, and a castle on the hill. “Cardenete: míralo y vete,” goes the refrain—“Cardenete: see it and get out.” Set against the side of a small valley, the village guarded the western approaches to an area known as the Tierras de Moya, a rugged corner of New Castile wedged in between the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia. Although settlement of the region dates back to prehistoric times, humankind’s hold on the Tierras always seemed provisional. Too rocky for extensive farming, the Tierras de Moya were more of a place for passing through: first it was the Romans on their way from Córdoba to Zaragoza, then the Moors from Valencia to Toledo, and finally the Christians fighting their way south from Soria to Murcia. After the reconquest of the area by the Christians in 1183, Cardenete and thirty-one other villages were incorporated into a seigneurial territory with its seat at Moya, a hilltop fortress that dominated the area. At the time of Bartolomé’s birth, the seigneury had only recently been elevated to the status of a marquisate, presided over by the royal favorites, Don Andrés de Cabrera and his wife, Doña Beatriz de Bobadilla.5

The fact of Sánchez’s birth was unremarkable. More remarkable was that he survived to adulthood, for aside from the usual high infant mortality, plague and famine were on the prowl during those years, especially in 1507. As an adult, Bartolomé recalled that in addition to his grown brothers and sisters, he had “others who died on me while they were quite small.”6 Like his father and uncles before him, Bartolomé Sánchez was brought up to be a farmer (labrador). In rural New Castile, to be called a labrador meant that one had achieved a certain status and economic independence in life; Sánchez’s father and uncles presumably all had access to some land and a few animals to work it. They were the lucky ones; as the century progressed, Sánchez’s generation found it increasingly difficult to maintain the status of a labrador. Many, like Bartolomé, slipped into the great underclass of landless day laborers, called jornaleros, whose only asset was the sweat of their brow.

3. View of Cardenete from the south, 1786. (“Relaciones Topográficas enviadas a Tomás López,” Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid; ms. 7298, f. 230)

One reason for the growing impoverishment of rural families such as Sánchez’s was the simple fact that there were too many people and not enough land. Plague or no, during the first half of the sixteenth century the population of New Castile was growing rapidly, finally replacing and then exceeding the demographic losses caused by the great Black Death of 1348–50. In the village of Cardenete, the natural increase of the population seems to have been augmented by some immigration from the Basque country and the mountains of nearby Cuenca.7 Most of the village’s residents were “Old” Christians; “old” because their ancestors had always been Christian and had never intermarried with converted Jews or Muslims, who were known as the “New” Christians or “converts” (conversos). All the same, even this fairly remote village harbored a community of converted Jews, some of whom had immigrated to Cardenete from the city of Cuenca and the kingdom of Valencia in the late fifteenth century. By 1528, immigration and natural growth had made Cardenete the largest village in the territory to which it belonged. With its 206 tax-paying households and two tax-exempt noble hidalgos, the village was wealthy enough to support two public notaries and a schoolmaster.8

From the authorities’ point of view, a growing population was viewed as a good thing. More subjects represented taxable wealth, but for the village of Cardenete, the increased population was a burden. More families meant more people and animals to feed when the village lacked the land to support them. Although Cardenete’s council lands were extensive, they comprised largely sterile rock and gravel, not at all the sort of soil needed for growing the cereals, vegetables, and pasture that made up the bulk of the villagers’ and their animals’ diet. In fact, so infertile was Cardenete’s arable land that the best of it could be cropped only once every four years, and in some places, just once every twenty years.9 Complicating matters, the inheritance laws of the time forced parents to divide their property equally among their children, so that each generation faced the dispersion of already insufficient landholdings. In poorer families such as Sánchez’s, the result was that no child received enough land to support himself unless he married well or found a way to buy out the other heirs. With many other siblings surviving to adulthood, Bartolomé appears to have been one of those unfortunate ones who wound up with too little land.

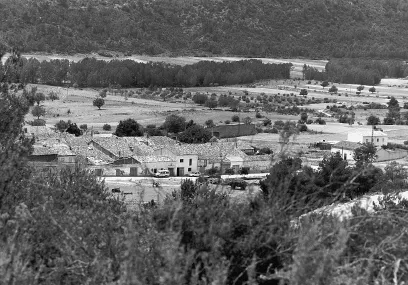

The lack of adequate farmland in Cardenete was critical for the entire village. While producing woolen cloth brought in extra income for many residents, it could not replace farming as a means of support. Around 1500, the village council, casting about for a way to increase the amount of arable land for its residents, entered into a long-term agreement with the lord of Víllora, who owned some fertile bottom land known as the Vega de Yémeda. In exchange for a yearly rent of 440 bushels of wheat, Cardenete acquired the land it needed plus a water mill. As the village council explained in a lawsuit in 1552, Cardenete “possesses sterile land, and cannot match cereal-producing lands as good as those [in Yémeda] … their principal sustenance and relief.” Even better, the Vega de Yémeda was a scant league away, although just far enough to place it over the border into the jurisdiction of the city of Cuenca.10 The acquisition of extra arable for the village, however, does not seem to have helped the extended Sánchez family. By 1553, three of Sánchez’s uncles and three of his siblings had picked up and left the village. The favored destination was Villamalea, a settlement thirty miles to the south on the edge of the flat expanse of La Mancha, a parched plain where the climate matched the famous proverb’s description of nueve meses de invierno y tres de infierno (nine months of winter and three of hell). Bartolomé, on the other hand, chose to stay in the village, where in 1532, at the relatively late age of thirty-one, he married Catalina Martínez, also from Cardenete. Her family had some land that she either brought to the marriage or later inherited, and with the little that Bartolomé had, for a while they made a go of farming. Meanwhile the children began to arrive. The couple’s eldest child, a daughter, was born in 1537 or 1538, and by 1552 there were three more girls and a boy, Bartolomico.11 Around 1550, when Sánchez was already an old man by society’s standards, he was forced to abandon farming and began to work on the margins of the economy as a jornalero and wool carder. Is it any wonder that a few years later, Sánchez, as an elderly father of five young children with no sure means of support, suffered a public breakdown in the parish church?

4. The Vega de Yémeda, agricultural land leased by Cardenete. (Photograph by the author)

3

Around the time of his breakdown, Sánchez’s family had witnessed more strange behavior, but they were in the dark as to its cause. Sánchez had been beside himself with some unnamed fear. He stopped eating and they had to force-feed him. He did strange things, such as taking a clay jug, placing a lemon within it, blessing it, and declaring that it was God the Father’s orb. At night he emptied the chamber pot in the street and said that the souls of the damned bathed and drowned in urine.12 One day he appeared so disoriented that his cousin Bartolomé de Mora and two others tied Sánchez up with rope, but when Sánchez exclaimed, “You have me tied to the column just like the Jews did to Christ—which of you is to give me the first lash?” they untied him and took him to the parish church. At the doorway, Sánchez removed his left shoe before entering. Concerned by his cousin’s behavior, Mora spent three nights with Sánchez, who was so agitated that it seemed his heart would leap right out of his body, and the poor man could not stay quiet—he kept on talking and repeating all of his prayers.

Mora became so worried that he took Sánchez to the village of Monteagudo, fifteen miles away, to see if Sánchez had some devil in his body that the priest there could recognize and exorcise. The priest saw the wool carder but could find no evidence of possession, and gave them some medicine for Bartolomé without telling them what it was.13 A few days later, Mora returned to Monteagudo with Sánchez so that he could pray for relief at the shrine of Our Lady of the Candles. Sánchez stayed there the whole day without being able to speak, and if they spoke to him, he was unable to reply; all he did was sob. Later, when he came to and they asked him why he had been that way, he said that he had seen some men in yellow hose who were coming to kill him. Mora and his friends were unable to see any part of what Sánchez said he had seen, so they returned home. In fact, Mora was certain that Sánchez during this time was not in his right mind at all, and when Sánchez went back to Monteagudo a third time without telling anyone that he was going to see the priest again, they were sure he had done some mischief to himself and they went out to look for him.14

Although Sánchez seemed beside himself with fear and anxiety, so much so that Mora began to wonder if his cousin had gone mad, Sánchez still uttered no word of explanation for his actions. This silence was all the more surprising because the wool carder knew perfectly well what was the cause of his anxiety, but he had taken an oath not to say anything about it. Sánchez’s travails had begun in 1550, around the time he gave up farming for himself. As he explained later, it happened this way:

Around St. John’s feast day in June,15 I was coming back from reaping at the Vega de Yémeda, which is next to Cardenete, no more than a half-league away. The sun had set, but it wasn’t night yet. Just as I was approaching a chapel that is called St. Sebastian’s, there appeared in the air in the form of a luminous image the figures of two men and a woman. The woman appeared to me to be in between the two men, and above the woman there appeared to be a bird, which with the tip of one wing touched the other. When I saw this, I went down on my knees and prayed right there five Paternosters with five Hail Marys, and after that, three Paternosters with three Hail Marys, all on my knees, begging God that if this were a good thing, to tell me so, and if not, to take it away. While I was doing that, the thing that I saw disappeared, and it seemed to me that I felt consoled in my heart, and so I went home and I never mentioned it to anyone. I went around always wondering to myself what that could have been until Lent [1551] came. I went to confess with Martín de Almazán, the old priest of Cardenete, and to do that I bought a book from Hernán Zomeño, which was a Roman rite book of hours in Spani...