![]()

1 THE FUGGER FAMILY IN LATE MEDIEVAL AUGSBURG

FUCKER ADVENIT

In 1367, the tax book of the city of Augsburg recorded the arrival of the weaver Hans Fugger. The immigrant paid a property tax of 44 pennies, which indicates a considerable estate worth 22 pounds. Hans Fugger initially lived as a renter in a house near the Church of the Holy Cross but was able to buy the house no later than 1378. One year after Hans’s arrival, Augsburg’s Achtbuch, a record of criminal investigations, mentions his brother Ulin (Ulrich) Fugger as a weaver’s manservant. From 1382 onward, Ulin also lived in his own house. According to the sixteenth-century Fugger family chronicle, the brothers came from Graben, a village situated on the Lechfeld to the south of the imperial city.1 After Ulin had died from an assault in 1394, his descendants can be traced in Augsburg for some fifty years before they disappear from the records. Hans Fugger’s descendants, by contrast, would come to play an important role in the imperial city over a much longer run.2

The plain first entry in the tax book—Fucker advenit—marks the beginning of the history of the family in the metropolis on the Lech River, and Fugger historiography has transformed Hans Fugger, the ancestor of the generations that would eventually become so successful, into a quasi-mythical figure who set a new course for the family’s history. Actually, however, the move from the countryside to the city was anything but unusual. The textile trades and long-distance commerce of Augsburg were flourishing at the time, and the favorable economic development attracted numerous rural weavers. As early as 1276, Augsburg’s city law code shows that cloth production for export was firmly established. This textile production probably included the city’s rural environs, for the Augsburg office of the linen inspectors (Leinwandschau), an institution for the quality control of cloth, also monitored the quality of textiles that had been produced in the countryside.3

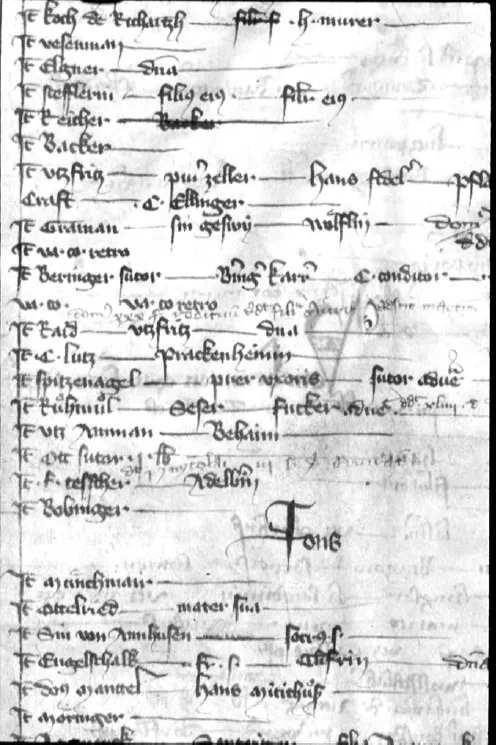

FIGURE 1

Fucker advenit. Entry for the weaver Hans Fugger in the Augsburg tax register of 1367.

(Stadtarchiv Augsburg, Reichsstadt, Steuerbuch 1367)

Important hints at Hans Fugger’s further career can be drawn from the family tradition, especially from the so-called Book of Honors (Ehrenbuch) of the Fuggers, a work commissioned by Hans Jakob Fugger and written by Clemens Jäger, an employee of the Augsburg city council, in the 1540s, as well as the “Fugger Chronicles” from the second half of the sixteenth century. According to the sources, Hans Fugger married Klara Widolf in 1370 and had two daughters with her. Klara may have been a daughter of Oswald Widolf, who became guild master of the weavers in 1371. With this marriage, if not earlier, he should have obtained the legal status of Augsburg citizen. Archival sources confirm that Hans Fugger was married to Elisabeth Gefattermann, a weaver’s daughter, in 1380. His father-in-law became guild master of the weavers in 1386, and Hans Fugger was elected to the Twelve—the guild’s leadership committee—in the same year. The Twelve were automatic members of the imperial city’s Grand Council, as well. Hans Fugger’s growing social status is also indicated by the fact that he became a guardian of the merchant Konrad Meuting’s children in 1389. In January 1397, Hans and Elisabeth Fugger purchased a house in the centrally located Augsburg tax district “vom Ror” from Heinrich Grau and his wife for the substantial sum of 500 Hungarian florins. A few years later, the couple also acquired rural property: In 1403, they spent 200 florins on a farmstead and adjoining land in the village of Scheppach to the west of Augsburg, and two years later they purchased a farmstead, four smallholdings (Sölden), and a plot of land in the village of Burtenbach. The house of his deceased brother Ulin in Augsburg’s Klebsattelgasse apparently became Hans Fugger’s property, as well.4

Augsburg’s tax books, which have been preserved in a virtually uninterrupted series from 1389 onward and which constitute an extraordinarily important source for urban social history in the late Middle Ages, allow us to trace the evolution of Hans Fugger’s wealth in more detail. To be sure, late medieval tax records are brittle and difficult sources, but thanks to the painstaking work of social historians, we know how they operated. Basically, every citizen of Augsburg had to declare his property. The tax system distinguished between liegend gut (real estate, as well as eternal and life annuities) and fahrend gut (the movable property, excluding the tax-exempt items of daily use). Real estate was taxed at half the rate of movable property. Citizens who did not own substantial property—always a large group in late medieval cities—paid the so-called Have-Nots tax (Habnit-Steuer). Before 1472, the tax rate, which was fixed annually by the imperial city’s Grand Council, usually oscillated between 1/60 and 1/240 of the declared property; afterward, it ranged between .5 and 1 percent. Citizens were not required to make a new property declaration each year, however; they only had to make a declaration every three to seven years in the so-called sworn tax years. Therefore, the commercial success of merchants manifests itself not in a gradual rise of their property tax but in marked leaps from one “sworn tax year” to the next. As the tax books record the payments only summarily, whereas real estate and movable property were taxed at different rates, moreover, the actual payments allow only a rough estimate of the actual property value. Researchers have found, however, that the city’s tax collectors calculated a “property assessment” (Anschlagvermögen) by adding the value of the movable property to half the value of the real estate. This property assessment provides the most important indicator for the reconstruction of the economic rise of the Fuggers.5 Clemens Jäger used the tax books as a source for his Book of Honors of the Fugger family as early as the mid-sixteenth century. “And it is true that we find in old tax books on many occasions,” Jäger wrote about Hans Fugger, the immigrant from Graben, “that he was rich above three thousand florins, which at that time was regarded as a really large amount of property.”6

The findings of modern historical research approximate Jäger’s estimate rather closely. They show that Hans Fugger had substantially increased his starting capital within less than three decades after his first appearance in Augsburg. According to the 1396 tax book, his property was assessed at 1,806 florins at that time, putting him in position 40 within the hierarchy of the city’s taxpayers. While he was still worlds apart from the richest citizen, the widow Dachs, who paid taxes on more than 20,000 florins, the immigrant weaver was already among the wealthiest 1 percent of Augsburg’s taxpayers and on equal economic terms with members of long-established patrician families such as the Portners, Langenmantels, and Ilsungs.7

How did Hans Fugger acquire this wealth? A century ago, the economist Werner Sombart expressed the opinion that he already came to the city with “considerable property” from the countryside. The economic historian Jakob Strieder emphatically disagreed with Sombart, however. In his view, Hans Fugger’s wealth only saw “a very substantial increase” after his immigration to Augsburg. This rise could only be caused by successful commercial activities.8 We do not have any hard evidence for Hans Fugger’s activities in long-distance trade, but it appears unthinkable that he earned his fortune at his own loom. In the years up to his death in 1408–9, Fugger’s economic career proceeded in an unspectacular way. His property assessment sank to 1,560 florins in 1399 before rising again to 2,020 florins in 1408.9

After 1408 Hans Fugger’s widow, Elisabeth, paid the property taxes. According to the older literature, she “held the property, and therefore the business, together until 1436.”10 This is a blatant understatement, however, for the tax books demonstrate that her property assessment continuously increased from one sworn tax year to the next (see table 1). By 1434, Elisabeth Gefattermann had more than doubled the wealth of her deceased husband and had reached position 27 in Augsburg’s wealth hierarchy. Even though precise information about her economic activities is lacking and the grown sons Andreas (Endres) and Jakob, who were assessed together with their mother in 1434, actively assisted her, Hans Fugger’s widow must have been a remarkably business-minded woman. She thus exemplifies a frequently observable, though long neglected, phenomenon: In late medieval and early modern trade, women were well able to hold their own.11

TABLE 1

Wealth of Hans Fugger’s widow, Elisabeth, 1413–1434

Year | Property assessment1 |

1413 | 2,860 florins |

1418 | 3,240 florins |

1422 | 3,960 florins |

1428 | 4,200 florins |

1434 | 4,980 florins |

In 1441, the first sworn tax year after their mother’s death, the brothers Andreas and Jakob, who had initially been apprenticed to a goldsmith, paid taxes on a combined property of 7,260 florins. The joint property assessment is a certain indicator that the brothers were engaged in business cooperation. From the fact that the tax books repeatedly recorded Jakob’s absence, we may further conclude that he represented the firm at other places. The brothers’ engagement in long-distance trade can be inferred from the fact that they belonged to a group of merchants to whom the city council issued a warning in 1442 for having bypassed a road leading through the territory of Duke Otto of Bavaria and having thereby evaded toll payments. Their tax assessments show, moreover, that their business was doing well. In 1448, the brothers owned 10,800 florins, the fifth-largest estate in the imperial city at the time. Only the powerful Peter von Argon, the heirs of Hans Meuting, and the widows of Hans Lauginger and Ulrich Meuting had more capital.12 But afterward the brothers parted ways: In the 1455 tax book they were assessed separately for the first time, Andreas at 4,440 florins and Jakob at 5,697 florins. This separation marks the beginning of the two family lines: the Fuggers “vom Reh,” named after a coat of arms showing a roe deer that, according to tradition, was conferred on the line in 1462, and the Fuggers “von der Lilie,” named after the lily on their coat of arms.13

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE FUGGERS “VOM REH”

Andreas Fugger died as early as 1457, and his widow, Barbara, a daughter of the merchant Ulrich Stammler, was able to preserve, though not increase, the family’s wealth during the following decade.14 Peter Geffcken, the leading expert on Augsburg’s economic history during this time period, assumes that Barbara Fugger invested in the trading company of her son-in-law Thoman Grander and that her son Lukas worked for the Grander firm. This assumption is mainly based on the fact that Lukas Fugger is first documented as an independent merchant in 1469, shortly after the death of his brother-in-law in 1467–68. Perhaps it was Lukas Fugger who continued the operations of the Grander company. Thoman Grander had begun his mercantile career as an employee of the important Meuting company and had gained admission to the Augsburg merchants’ guild with his marriage to a daughter of Hans Meuting the Younger in 1449. After the death of his first wife, he had married Barbara Fugger, a daughter of Andreas Fugger, in 1453–54. By 1460, Thoman Grander’s firm had a branch office in Nuremberg. According to the Fugger Book of Honors, he was “an eminent merchant of Augsburg.”15 Grander’s brother-in-law and presumable successor, Lukas Fugger, first appears as an independent taxpayer in the Augsburg tax book of 1472. Over the following two decades, his wealth steadily increased.

The rise of Lukas Fugger’s wealth (see table 2) mirrors the success of his trading company, whose associates were his younger brothers Matthäus, Hans, and Jakob. The Fuggers’ Book of Honors states that he had an “enormous trade … with spices, silks, and woollen cloth”.16 The mainstay of this “enormous trade” was the textile business. The protocols of the Augsburg city court (Stadtgericht) record numerous lawsuits that Fugger’s representatives Stephan Krumbein, Bernhard Kag, and Hans Stauch filed against weavers who had received cotton or wool and had failed to deliver the finished cloth on time. Commercial ties with Italy were also of great importance to the firm. In 1475, the brothers Lukas and Matthäus Fugger obtained a ducal letter of safe conduct for their trade with Milan, a center for the production of and commerce in high-quality fabrics and luxury items. According to the sixteenth-century “Fugger Chronicles,” Matthäus died on a journey to Milan in 1490. In Venice, the most important distribution center for cotton from the eastern Mediterranean, the sons of Lukas Fugger’s uncle Jakob represented his firm for ...