![]()

1

What Are My Choices?

THE GROWING DIVERSITY IN HIGH-PROFILE

STATEWIDE BLACK CANDIDATES

In 2004, two major party African American candidates competed for Illinois’s U.S. Senate seat. The Democratic nominee was Barack Obama, who ran a campaign that was celebrated for its ability to reach across the aisle. In endorsing Obama, the Springfield State-Journal Register noted that “Obama receives our support for many reasons, but one of the most striking differences between these candidates comes down to inclusiveness versus exclusiveness. Obama represents the former.”1 One viewer of the 2004 Democratic National Convention praised Obama for his centrist appeal. “I watched a little of the convention . . . and was unimpressed with most of the Bush bashing. However, that Barack Obama is one to watch. He is very charismatic and stayed away from most of the partisan rhetoric. If he manages to keep a centrist message, he may well be our first black president.”2 In addition to Obama’s skilled and well organized campaign, he was fortunate to be the Democratic nominee in a left-leaning state that had previously elected a black U.S. senator.

Even more fortuitous for Obama was that his black Republican opponent, Alan Keyes, ran a campaign that alienated even the most conservative voters. Keyes hoped to gain traction by making inflammatory statements, and as one Chicago Tribune writer noted, he did not disappoint.3 During the course of the campaign, Keyes equated abortion with terrorism.4 He later argued that Jesus would not vote for Obama because of his support for pro-choice policies.5 Keyes’s problems with voters went beyond his controversial campaign style. Keyes was not from Illinois and was too conservative for many voters in the state. The only reason he was on the ballot was because the previous Republican nominee, Jack Ryan, had resigned after a scandal involving his ex-wife. The poor timing of Keyes’s candidacy and his undisciplined campaign strategy helped Obama win the U.S. Senate seat by almost a three-to-one margin.

The 2004 Illinois U.S. Senate election provides both a perfect example of how black candidates should campaign if they hope to succeed in majority white contexts and a good example of how black candidates can sabotage their candidacies. Several political scientists suggest that for black candidates to prosper they must campaign on issues that transcend race. They must also have significant political experience and campaign in a favorable political context.6 Obama satisfied all of these criteria, whereas Keyes did not. The differences in these two campaigns are emblematic of the wide range of black candidates who compete for high-profile statewide office. Some candidates have significant political experience and run in favorable settings, but focus on racial issues. Others have significant political experience, and they run deracialized campaigns, but compete against well-qualified opponents in politically unfriendly contexts. Still others, like Alan Keyes, follow none of the prescribed criteria.

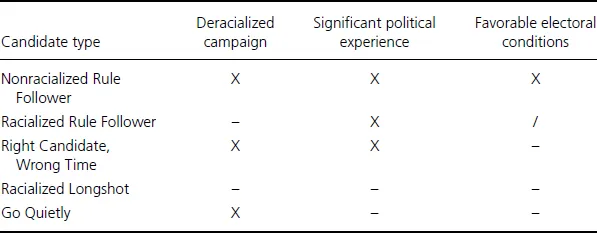

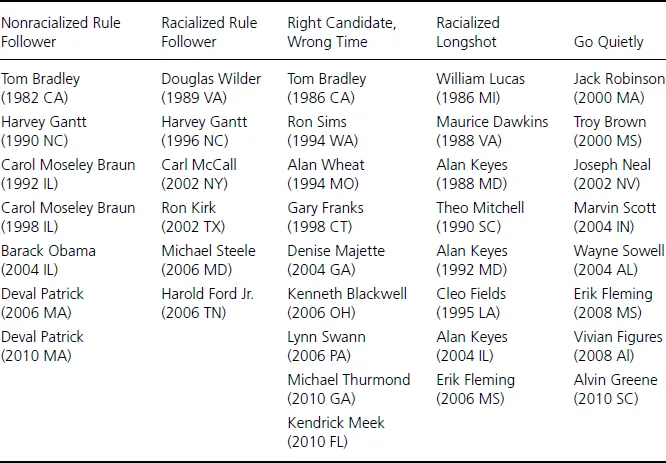

The growing number of high-profile statewide black candidates has yielded a lot of diversity in these candidates’ qualifications, campaign strategies, and partisanship. Additionally, they are campaigning in vastly different contexts, and the quality of their opponents varies significantly. Using this diversity, I disaggregate U.S. Senate and gubernatorial black candidates into five categories: Nonracialized Rule Follower, Racialized Rule Follower, Right Candidate at the Wrong Time, Racialized Longshot, and Go Quietly.7 These categories are created using prescribed criteria that black candidates should follow if they hope to succeed in majority white contexts. In particular, the candidates will be disaggregated based on whether they ran a racialized campaign, as measured by the criteria outlined in the first chapter, their levels of political experience, and the political context in which they campaign. The review of these candidates will provide a contextual understanding for the campaigns I analyze in the first half of this study.

How Black Candidates Can Succeed in Majority White Settings

In spite of the precipitous growth in the number of black candidates campaigning for high-profile statewide office, the fact remains that few will succeed in their quest to be governor or U.S. senator. One of the primary reasons for their dismal success rate is that blacks form no more than 40 percent of the population in any state and no more than 21 percent of the population in states outside of the South.8 Thus black candidates must rely on a large number of often reluctant racial crossover voters in order to succeed.9 While there may be some disagreement about what it takes for black candidates to prosper in these majority white contexts, many social scientists and accomplished black politicians agree that most competitive black candidates will have similar characteristics.

Political scientists and pundits argue that black candidates should deemphasize race and steer clear of racially divisive issues and political figures to increase their appeal to white voters, who make up the plurality or majority of voters in every state.10 By focusing on issues that transcend race and demonstrating their political independence from the black community, black candidates can minimize concerns that they will favor one racial/ethnic group.

TABLE 2. Candidate types and characteristics

X = Indicates that the candidates satisfied this criterion.

/ = Indicates that the candidates partially satisfied this criterion.

– = Indicates that the candidates did not satisfy this criterion.

Some have suggested that black candidates have a more difficult time appearing viable without previous elected experience. Senator Edward W. Brooke III (R-MA. 1966–78), the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction, noted, “It is not only important for the black candidate to be as qualified as his white counterpart, . . . in most cases you have to be twice as good as your white competitor if you hope to stand a chance.”11 A substantial percentage of white voters believe that all else being equal, white candidates are better suited for elected office than their black counterparts.12 To offset this stereotype, black candidates should have significant political credentials.

Others contend that blacks have the best opportunities to succeed in states that favor their political party.13 Given that black candidates face a number of disadvantages, including lower levels of support from white voters and difficulties raising funds, they are most likely to overcome these disadvantages if they campaign in friendly political contexts. Some have suggested that Obama’s victory in 2008 was substantially bolstered by the Democratic-friendly political climate.14 Table 2 summarizes these attributes and displays the different categories of black candidates and which criteria they satisfied. Table 3 lists the candidates in each category.

Nonracialized Rule Follower

Every once in a while, everything falls into place. The Nonracialized Rule Followers satisfy all of the prescribed guidelines that are necessary for them to succeed in majority white electorates. As a result, four of the seven black candidates in this category have been successful in their bids for statewide office, and the three who failed lost in very close elections. Most of the candidates in this category have significant political experience. Some, such as 1982 California gubernatorial candidate Tom Bradley and 1990 North Carolina U.S. Senate candidate Harvey Gantt, served as mayors of large cities. In addition to their experience, these candidates de-emphasize race in their campaigns. The 1992 Illinois U.S. Senate candidate Carol Moseley Braun, for example, ran on a platform that emphasized women’s rights and lowering taxes for the middle class. Tom Bradley’s campaign focused on controlling crime by advocating for harsher penalties for criminals. Moreover, many of these candidates demonstrated their independence from the black community by avoiding other black leaders and appearances before majority black audiences. Washington Post reporter Huntington Williams notes that 1990 U.S. Senate candidate Gantt, unlike his white predecessor, 1984 Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Jim Hunt, stayed away from other African American political figures. “Unlike Hunt’s campaign in 1984, when Jesse L. Jackson made much-publicized voter registration visits to North Carolina . . . Gantt’s effort was very low-profile. Jackson and other black politicians have reportedly been asked to stay out of North Carolina for this race.”15 While many political commentators praised these candidates for their post-racial campaigns, several faced criticism from the black community for not doing enough to represent their interests.16 These candidates coincidently did not vary in their partisanship. All of the Nonracialized Rule Followers represented the Democratic Party.

Their abilities and experience are not the only things going in their favor. The Nonracialized Rule Followers also campaign in states that hold favorable views of their parties. Deval Patrick, Obama, and Moseley Braun ran in Massachusetts and Illinois, which have a long history of supporting Democrats and black politicians. Only one of these candidates ran against an incumbent, and most had more political experience than their opponent. Deval Patrick’s 2010 campaign for governor of Massachusetts exemplifies the candidates in this category.

Deval Patrick

In 2010, Deval Patrick became the first African American to run for reelection as governor. Despite being the incumbent, and thus more experienced for the position than his opponents, the economic recession in Massachusetts made Patrick’s reelection bid far from certain. Several polls conducted by the Boston Globe early in 2010 showed that a majority of the electorate was unhappy with Patrick’s performance.17 To make matters worse, Patrick was a Democrat in a year when Democrats were unpopular. Even the consistently Democratic state of Massachusetts had elected a Republican, Scott Brown, to the U.S. Senate earlier in the year.

TABLE 3. Candidates by type

While the context in some ways was hostile for Patrick, several things went in his favor. First, he ran unchallenged in the primaries and had the strong support of his party. Second, he would benefit from the independent candidacy of Tim Cahill, who previously served as state treasurer. Cahill was very well funded, and his campaign siphoned off many key votes from the Republican nominee, Charlie Baker. The inclusion of two candidates split the Republican vote and gave Patrick the opportunity to be reelected in a tough economic climate. Finally, Democrats maintained a three-to-one registration advantage over Republicans in Massachusetts.18 Even in an unfavorable year for Democrats, Patrick still ran in a state that overwhelmingly supported his party.

Like the other candidates in this category, Deval Patrick’s reelection campaign focused on issues that transcend race. In particular, he focused mostly on economic issues. While the unemployment rate and the deficit grew in Massachusetts during Patrick’s tenure, he explained that the measures he took as governor, including raising the sales tax, helped prevent Massachusetts from declining as much as other big states such as California. He also highlighted his opponents’ mismanagement of the construction project known as the “Big Dig” to illustrate that they did not have the capability to bring Massachusetts out of the recession.19 Patrick’s opponents also shied away from racial issues. Instead, his opponents primarily attacked Patrick on fiscal issues. They also argued that Massachusetts would be better served with a divided government.

As the campaign progressed, many of Cahill’s supporters began to switch their allegiance to Republican Charlie Baker. Despite large defections of Cahill supporters, Deval Patrick was able to win reelection with less than a majority (48 percent). Overall, his qualifications as someone who could succeed at the state level, his centrist nonracialized campaign strategy, Massachusetts’s left-leaning electorate, and the good fortune of having two conservative leaning candidates in the election helped Patrick become the first African American to be reelected as governor.

Racialized Rule Follower

Generally, black candidates with significant political experience do not use racial appeals in their campaigns. However, there are instances in which viable black candidates utilize subtle or even overt appeals to members of their racial group to mobilize their base. The Racialized Rule Followers all have significant political experience. Some, like 2006 Maryland U.S. Senate candidate Michael Steele and 2002 New York gubernatorial candidate Carl McCall, held state offices. Others, like 2006 Tennessee U.S. Senate candidate Harold Ford Jr., were prominent congressional representatives. While these candidates do not always campaign in the most supportive political contexts, almost all in this category ran for an open seat rather than campaigning against an entrenched incumbent. Moreover, many of these candidates took centrist positions. Ford ran a campaign in which he highlighted his religion and advocated for fewer regulations for gun owners. Michael Steele supported more stringent limits on stem cell research and advocated for a federal ban on gay marriages.

While the Racialized Rule Followers share many of the same attributes as their nonracialized counterparts, they do not completely ignore race. In fact, many use what Franklin (2010) describes as a situational deracialization strategy. According to Franklin, these candidates present a deracialized portrait of themselves to majority white audiences and many media outlets. As a result, they advocate for the same issues as their nonracialized counterparts. However, candidates who use a situational deracialization strategy also use positive race-conscious appeals to black audiences and make a concerted effort to demonstrate their symbolic connection to the black community. Thus it is not uncommon for Racialized Rule Followers to highlight the positive implications of their candidacies for the black community. Ford, for example, made several racial appeals including telling a black church, “If you fight for me for the next forty-eight hours against these forces that want to turn us back, I will fight for you every single day in the United...