![]()

1

Reading

Estos ejemplos, que al azar de mis lecturas he ido anotando, podrían, sin mayor diligencia, multiplicarse . . .

EVARISTO CARRIEGO

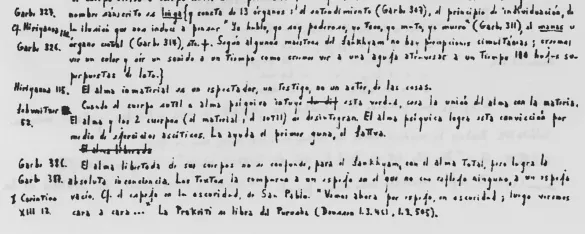

One of the most notable features of Borges’s manuscripts, particularly those of his essays and lectures, is the profusion of bibliographical references in the left margin; these are sometimes rather cryptic due to a system of abbreviations. Laura Rosato and Germán Álvarez crack some of this code in the introduction to Borges, libros y lecturas, in which they list a number of these abbreviations (32–33). Their transcribed annotations connect in a tight system with the notes in the left margin of the manuscripts, so that, for instance, in the manuscript of a lecture on Buddhism from 1950 (published by Alicia Jurado in Borges, el budismo y yo), the reference to “Garbe 327” (figs. 21, A36) on page 10 of the manuscript (page 45 of the book) connects to a reference in the second volume of Garbe’s Die Samkhya-Philosophie: Eine Darstellung des Indischen Rationalismus (Rosato and Álvarez 149). Similarly “Garbe 387” (45), a reference to an empty mirror that Borges compares in the margin to 1 Corinthians 13:12 (Paul’s “through a glass darkly”) also appears in Rosato and Álvarez (149). There are also references that are internal to Borges’s own works, as can be seen on page 17 (52 of the published version) of the same manuscript (figs. 22, A37). Here the reference to the famous (but perhaps apocryphal) Heraclitus fragment and the quotation from Plutarch had already appeared in the plaquette version of “Nueva refutación del tiempo” (1947), as had the quotation from the Camino de la pureza (see Obras completas 763, 770, 771). He has not checked the quotations again against some original, satisfied that he got them right the first time. The books represented in Rosato and Álvarez were just a fraction of the books in which Borges wrote—they are currently working on a second volume, and then perhaps there will be a third—but the sample is sufficient to confirm exactly how Borges used his reading in his writing.

Fig. 21. References to Garbe’s Die Samkhya-Philosophie, from manuscript of a lecture on Buddhism from 1950 (see fig. A36).

Fig. 22. Reference to Borges’s own “Nueva refutación del tiempo,” from manuscript of a lecture on Buddhism from 1950 (see fig. A37).

The system of work was as follows, then: when Borges read a book he would note down the page reference and a few words of a quotation in the original language, or occasionally write a brief paraphrase, and when he was writing something he would check the quotation for precision, rendering it into Spanish or paraphrasing it.

“Sobre el ‘Vathek’ de William Beckford” (“On William Beckford’s Vathek”)

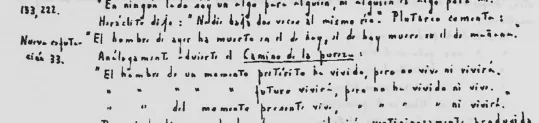

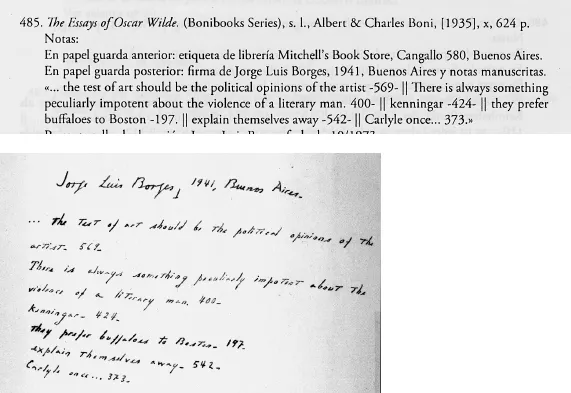

I will start with an example from one of the less-studied essays in Otras inquisiciones, Borges’s most important collection of essays (published in 1952). An example of a textual beginning—what rhetoric (and later genetic criticism) calls an “incipit”1—is the first sentence of the essay “Sobre el ‘Vathek’ de William Beckford” (1943), a text remembered mostly for the boutade that in the case of the Beckford novel, “el original es infiel a la traducción” (732; the original is unfaithful to the translation [Selected Non-Fictions 239]). The essay begins: “Wilde atribuye la siguiente broma a Carlyle: una biografía de Miguel Ángel que omitiera toda mención de las obras de Miguel Ángel” (729; Wilde attributes this joke to Carlyle: a biography of Michelangelo that would make no mention of the works of Michelangelo [Selected Non-Fictions 236]). With the help of Rosato and Álvarez, it is possible to find the precise source: they note that Borges writes at the end of the 1935 Boni edition of The Essays of Oscar Wilde the following brief phrase: “Carlyle once . . . 373” (fig. 23).

Fig. 23. Transcription and image of Borges’s marginalia in The Essays of Oscar Wilde, from Rosato and Álvarez’s Borges, libros y lecturas.

Rosato and Álvarez transcribe from page 373 the following words from Wilde’s essay “Coleridge’s Life”: “Carlyle once proposed in jest to write a life of Michael Angelo without making any reference to his art, and Mr. Caine has shown that such a project is perfectly feasible” (353), from a commentary on the biography of Coleridge published by Hall Caine in 1887. In the Borges essay another biography is at stake: that of William Beckford by Guy Chapman, published by Scribner’s in 1937, which does indeed lack an extended discussion of the novel Vathek, as Borges states in his essay, though it includes passing references to the book. Borges’s essay, after the opening reference to Carlyle, continues:

This connects to the comments on the paradoxes of writing biographies that can be found at the beginning of the second chapter of Evaristo Carriego in 1930: “Que un individuo quiera despertar en otro individuo recuerdos que no pertenecieron más que a un tercero, es una paradoja evidente. Ejecutar con despreocupación esa paradoja, es la inocente voluntad de toda biografía” (113; That an individual should want to awake in another some memories that belong only to a third is an obvious paradox. To fulfill this paradox casually is the innocent desire of every biography).3 That is to say, Borges has a deep and long-lasting concern with how to write a life, in his essays as well as in his stories.

The reference to Carlyle forms part of a series of quotations. It is not found in the published works of Carlyle but rather in the diary of William Allingham (unpublished until 1907, but obviously available to some readers in the years before); it also appears in the biography of John McNeill Whistler by Joseph and Elizabeth R. Pennell (1908); in these sources it is clear that Carlyle was not jesting.4 Borges simply repeats (and translates) Wilde’s comment on Carlyle’s “jest.”

An examination of Borges’s sources will often point beyond the immediate context of the words quoted because the quotation indicates an interest in other series of textual details that are also pertinent to the interpretation of Borges’s texts. In this case it is worth noting that the section of the Wilde book in this particular collection is a series of brief reviews that Wilde wrote about recent biographies: of Ben Jonson, Longfellow, Coleridge, Dickens, Dante Gabriel Rossetti,5 and George Sand, the majority of them published in the Great Writers series funded by Walter Scott (1826–1910), not the Scottish novelist but an industrialist in Newcastle upon Tyne who founded a publishing house intended to bring the classics to readers of modest means. Wilde’s opinions about the series tend to be negative. With regard to the biography of Coleridge, he writes: “for all that, it is not the real Coleridge, it is not Coleridge the poet” (372). He continues:

This is followed by the paragraph that opens: “Carlyle once proposed in jest to write a life of Michael Angelo without making any reference to his art, and Mr. Caine has shown that such a project is perfectly feasible.” Wilde continues:

What is notable here is Wilde’s insistence on the inner life of the creator. This can be related to Borges’s strategies in the essay on Beckford, which accounts for Beckford’s life in part of a sentence—“William B...