![]()

1

“YOU DAMN YANKEE WHAT BROUGHT YOU HERE?”

. . .

. .

.

The British garrison of Fort Niagara received some uninvited guests on the morning of August 1, 1783. The fort’s commander, Brigadier Allan Maclean, expressed his “great surprise” at the arrival of “three Batteaux’s … from Schnectady Loaded with Rum to trade at the Upper posts.”1 The traders, who had successfully slipped past Major John Ross, the commander of Fort Oswego, presented Maclean with papers and certificates from U.S. general Philip Schuyler, New York governor George Clinton, and the mayor of Albany requesting safe passage to Detroit and Michilimackinac.

Maclean was at a loss as to what to do with the New Yorkers. He explained to the traders “how improper it was in them; to come to trade here so soon, Even before the Definitive treaty of Peace was signed, or before the commercial Treaty had been ratified and concluded.” Maclean was loath to turn them away, because he was “afraid it might be looked upon as an act of violence in me.” Instead, he allowed the traders to remain at Niagara and ordered Ross at Oswego to stop all boats arriving from Schenectady while he awaited urgent instructions from General Sir Frederick Haldimand, the governor of Quebec.2

The British commandant was not alone in his desire to wish away the New Yorkers. The Americans’ presence angered the king’s Indian allies at Niagara, who felt betrayed by their exclusion from the British-American peace negotiations in Paris. The British commandant reported an ugly confrontation between “five or six Indians half drunk” and the Montreal merchant Isaac Todd, who had only recently returned from London where he been a member of the contingent of Canada merchants who met with Lord Shelburne and Richard Oswald. Mistaking Todd for a New Yorker, the Indians “told him in broken English ‘You damn Yankee what brought you here.’” Luckily, a British Indian agent intervened to save the startled Todd from the disastrous consequences of this case of mistaken identity. Still, Maclean noted that “our Indian friends look at these People very crooked indeed.”3

The incident at Niagara helps to recover the pervasive uncertainty on the imagined border at the end of the American War of Independence. Fixing the boundaries of the new American nation was not simply a matter of surveying the physical geography of the trans-Appalachian West. The ambiguity of the border had less to do with the geographical ignorance and geopolitical arrogance of diplomats in Paris than it did with unresolved questions about the relationship between the American Republic and the British Empire. The presence of Maclean and his brother officers at Oswego, Detroit, Michilimackinac, and other western posts revealed the tension between the border as it was located by the preliminary peace settlement and the geopolitical realities on the ground. Moreover, as Isaac Todd discovered almost to his peril, the boundary between American and British nationals was difficult to distinguish.

Maclean may have taken comfort from knowing that the confusion he faced at Niagara was likely only a temporary period of uncertainty which further negotiations would help to resolve. As he pointed out to the Schenectady traders, British and American diplomats would soon negotiate a definitive peace treaty and a commercial agreement that would resolve many of the unanswered questions about the relationship between the peoples of the British Empire and the United States. Moreover, the anger of Indians at Niagara paid testament to the ongoing hostilities between the king’s Native allies and the United States. The decision of the Paris negotiators to exclude Indians from the diplomatic process meant that American and Native diplomats would need to conclude their own peace in North America. Haldimand exploited the inconclusive character of the peace to order the New York traders to return to Schenectady. He also refused the request of George Washington’s agent, Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, to prepare for the transfer of the western posts.4 While the peace process remained incomplete in 1783, British and American ministers were due to renew their negotiations in Paris in the spring, and the American Congress began taking steps to negotiate peace with the hostile Indian nations of the trans-Appalachian West in May.5 Surely it was simply a matter of time before the final pieces of the border settlement fell into place.

It was not. Agreement proved elusive in both Paris and North America. In Paris, the initial optimism of British and American diplomats that they could easily reconstitute their transatlantic trade along lines of commercial reciprocity and mutual interest proved ill-founded. While the idea of full commercial reciprocity among nations was an important tenet of the United States’ republican foreign policy, the principle proved divisive among British politicians, many of whom cherished the mercantilist Navigation Acts governing the imperial economy as the bulwark of national greatness. In more concrete terms, a deal could not be done that would clarify the operation of the boundary between the United States and British North America because the British and American diplomats were at loggerheads over trade between the United States and Britain’s West Indian colonies. It was one thing to welcome the United States into the European system of liberal national trade by offering Americans the status of most favored trading nation; it was quite another to allow the United States free access to Britain’s valuable Caribbean colonies.

In the trans-Appalachian West, negotiations between the United States and the Indian nations of the Ohio and Illinois countries failed to clarify American claims to sovereignty in the region. The United States insisted on negotiating with the Iroquois and western Indian nations as victors because American policymakers were determined to undermine the sovereignty of Native peoples. Most clearly demonstrated by the American peace commissioners literally holding hostage leaders of the Iroquois and western nations to extract land concessions as the price of peace, the refusal of the United States to deal with Indians on the basis of reciprocity was also part of proving American nationhood. By dictating peace terms, the United States acquired Native homelands that American colonists could transform into farms, villages, and towns that would substantiate American imperial claims in the trans-Appalachian West. Perhaps more importantly in the minds of American policymakers, the unequal terms of these treaties also elevated the status of American nationhood by diminishing the sovereignty of the Indian nations residing within the territorial boundaries of the United States. As it turned out, the Indians were not defeated peoples, and the tiny U.S. Army could not back up the diplomatic bullying of American policymakers with armed force. By the end of 1786, a pan-Indian confederacy formed by the Mohawk Joseph Brant and western war captains organized collective armed resistance to American imperial ambitions north of the Ohio River that revealed the geopolitical weakness of the United States.6

Despite all the indications that negotiations would help to resolve uncertainty on the border, the confusing situation at Niagara became the norm. British soldiers garrisoned what were supposed to be American forts. The Montreal fur trade continued much as it had done for the past twenty years. But for thousands of merchants, traders, and hunters, the uncertainty surrounding the northern border of the American Republic remained deeply unsettling. At its heart, Montreal’s fur trade was a commercial venture. Yet its success depended on networks of kinship and friendship, patronage and dependence, which bound together diverse polyglot peoples from across the Atlantic World and the North American continent. This world might survive while British agents controlled the means of movement along the boundary, but, given the shifting geopolitical tides of empire, how long would this last?

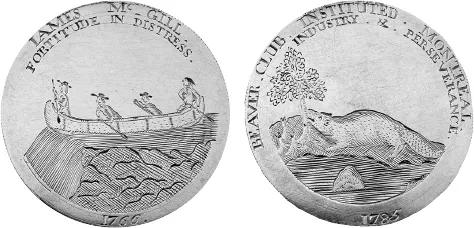

Montreal merchants founded the Beaver Club in 1785. The commercial promise of the St. Lawrence River had lured enterprising merchants from around the British Atlantic World to Montreal after the fall of New France in 1760. Irish traveler Isaac Weld recorded that “winter in Canada is the season of general amusement. The clear frosty weather no sooner commences, than all thoughts about business are laid aside.” The Beaver Club served as a center of the social life of Montreal, a town renowned for the “constant and friendly intercourse” among its residents, which gave the impression that “the town were inhabited but by one large family.”7

At first glance, the Beaver Club seems to look little different than the numerous mercantile organizations and gentlemen’s clubs found in any of the great commercial cities of the eighteenth-century Atlantic World. While the club did not maintain its own premises (it usually met in the Montreal Hotel), it provided its members with a venue to discuss politics, transact business, and entertain ship captains and visiting merchants with lavish dining and an excellent wine cellar.8

On closer inspection, however, a guest from London or Philadelphia would notice that the Beaver Club and its members differed from their counterparts in other cities. All of the club’s members had wintered in Indian Country. Each member wore a gold medal, hanging by a sky-blue ribbon, on his chest. The medal was inscribed with the Beaver Club’s motto—“Fortitude in Distress”—on the front, while the reverse recorded its owner’s membership number in order of the year in which he first wintered in Indian Country, beginning with Charles Chaboillez in 1751. At dinner, guests would note that a toast to the Catholic “Mother of All Saints” preceded the loyal toast to the Protestant King George III. Guests would feast on exotic fare, such as roast beaver and pemmican, served on the club’s specially commissioned silver plate, alongside the familiar madeira and port served in the club’s own crystal. After dinner, members smoked tobacco in Indian calumets and sang traditional French river songs, such as “A la clare fontaine,” before grabbing whatever furniture or accouterments came to hand to use as paddles in an imaginary canoe.9

The traditions of the Beaver Club reflected the French, Indian, and British worlds in which its members lived.10 The silver and crystal adorning the club’s well-kept table demonstrated the refined tastes of Montreal merchants, who had a voracious appetite for British consumer goods. At the same time, the club’s members combined their performance of European gentility with their shared experiences as North American adventurers. The after-dinner entertainment recalled the apprenticeship that merchants served as clerks or junior partners wintering in the hunting grounds of the Great Lakes and trans-Appalachian West. For young men, many of whom had only recently arrived in North America, the first winter in Indian Country was an introduction to a foreign world. Wintering was not merely a lesson in privation or a test of masculinity; rather, it was an important introduction to French and Indian culture and rituals, which governed Montreal’s fur trade during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Membership in the Beaver Club reflected an individual’s success in straddling these different cultures, so it was only appropriate that the club’s rituals embraced overlapping French, Indian, and British traditions.

The Treaty of Paris threatened to tear these worlds apart. As Canada merchants in London warned Lord Shelburne in January 1783, the proposed international border dividing the American Republic from the British Empire “cuts off all the Trading Posts and almost all the Indian Nations; the Trade with whom was the grand object of the commercial Intercourse between Great Britain and the province of Quebec.”11 London was the metropole of imperial trade, and Montreal merchants depended on their business connections in the British capital to extend them credit, supply them with manufactured Indian trade goods, and provide them with a market for their furs. Eight representatives of London merchant houses trading with Quebec signed petitions to the British government protesting the provisional treaty in early 1783, alongside the Montreal merchants Isaac Todd and Charles Patterson.12 Alexander Ellice was among the most prominent London signatories. Born in Scotland in 1743, Ellice began his career as a merchant in Schenectady, New York, in the 1760s. In partnership with James Phyn and John Porteous, Ellice pursued the fur trade of Detroit and Michilimackinac before the Continental Congress’s nonimportation policies forced the merchants to shift their business to Montreal, where Isaac Todd served as his agent. By 1783, Alexander Ellice was traveling between the London office of Phyn, Ellice & Company and the Montreal branch run by his brother Robert Ellice and his nephew John Forsyth. While Phyn, Ellice & Company expanded its trade to British colonies from Newfoundland to the West Indies, the company maintained its interest in the Montreal fur trade. With the death of Robert Ellice in 1790, his nephews John Forsyth and John Richardson took over control of the Montreal office under the new name of Forsyth, Richardson & Company.13 Richardson would prove one of the most aggressive advocates of Montreal’s fur trade until after the War of 1812. In London, Phyn and Ellice (Phyn, Ellices & Inglis after 1787) filled their correspondents’ orders for Indian trade goods and sold their furs at annual auctions. While London served as the main fur exchange, most of the lots bought at auction ended up on the European market. The final destination of the furs depended on their type, but Russia, France, and the German and Italian states were important re-export markets for the Montreal fur trade.14

Montreal was the commercial capital of the fur trade in the Great Lakes in 1783. While the Hudson River Valley had traditionally been the center of the English fur trade in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the fall of New France in 1760 opened up commercial competition between Albany and Montreal within the British Empire. By 1776, Montreal merchants had largely defeated their New York rivals for control of the fur trade, aided by the expansion of Quebec’s provincial boundaries to include the Ohio River Valley in 1774, and by the disruption that the Continental Congress’s policies of nonimportation and nonintercourse wrought on the merchants of Albany and Schenectady, who also depended on London connections to maintain their trade.15

Montreal and its suburbs numbered around eighteen thousand residents in 1790. An English visitor in 1785 thought the town’s location beautiful and its climate mild and healthy when compared with Quebec, though he maligned both the muddy, unpaved streets and the inelegant stone houses that lined them.16 Isaac Weld recorded that “by the far greater number of the inhabitants of Montreal are of French extraction; all the eminent merchants, however, and principal people in the town, are either English, Scotch, Irish, or their descendants.” The Canadiens seldom spoke any English, Weld noted, while the British residents of the town were “for the most part, well acquainted with the French language.”17 Ethnic divisions, however, were le...