![]()

1

A City in Recovery

On the night of November 22, 2003, three hundred Richmonders gathered at an old gun foundry on the banks of the James River. Once the Tredegar Iron Works had been the industrial heart of the city and its walls had echoed with the sound of hammers and the roar of furnaces. Now a solitary cannon reminded visitors of past glories.

Set in one of America’s most historic cities, Tredegar had seen its share of drama. But those who built it could not have imagined the history that would be unfolding on this night.

The first Europeans arrived in Virginia in May 1607, followed by the first Africans twelve years later. Ten days after arriving at Jamestown, Christopher Newport and Captain John Smith, with a small boatload of English settlers, spent several days exploring the river. They made their way up to the fall line, the farthest navigable point, where the city of Richmond now stands. At the time, several Algonquian tribes, united by a powerful chief named Wahunsunacock, or Powhatan, as he was called by the Europeans, made their home there.

The subsequent interactions of Europeans, Africans, and the native population were marked by tragedy and cruelty. The enduring legacy of mistrust, wounds, and inequities represent, as many observers have noted, America’s defining moral challenge.

In 1983, L. Douglas Wilder, a Virginia state senator who would become the nation’s first elected black governor, underscored the extent to which entrenched racism had hampered the region: “Virginia, having singularly provided significant leadership for the colonies from the earliest years, was also credited, tragically, as the leader in the gradual debasement of blacks through its ultimate institutionalization of slavery.”1

As the state’s capital, Richmond symbolizes America’s unfinished business. Few American cities combine such a potent mix of events and memories. Yet, four hundred years after Newport and Smith first ventured up the river, Richmond is the surprising seedbed for a movement of dialogue and trustbuilding that could have far-reaching implications for America—and for a world torn by racial, ethnic, and religious conflict.

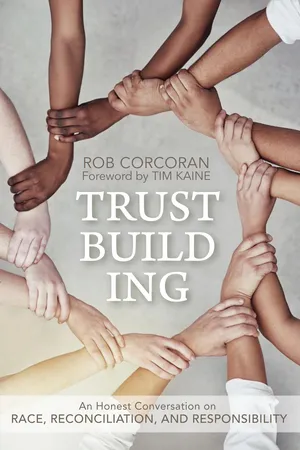

In June 1993, this former slave market and capital of the Confederate States during the American Civil War attracted national attention with a bold public acknowledgment of its unspoken history and with a call for “an honest conversation on race, reconciliation and responsibility.” Leaders of government, business, nonprofit organizations, and different faith groups joined residents of the inner city and farthest suburbs in an effort to address the “toxic issue of race” and build a vision of justice and reconciliation. Many of these leaders were at Tredegar to mark a decade during which this southern city had begun to free itself from the grip of its past. Reaching beyond Richmond, this effort represented a sustained bid to reframe a national debate on race marked by recrimination, resentment, guilt, and denial.

At the far end of the great foundry, a multiracial chorus quietly began a rendition of “Non Nobis Domine.” As the music rose over the oak cross beams to the vaulted ceiling, projected images of a city and its history appeared behind the singers. The crowd murmured as it recognized its heroes.

Dr. Robert L. Taylor, just risen from a hospital bed, was one of the first to arrive, walking slowly but with immense dignity and determination with his wife, Dorothy. A veteran civil rights warrior and cofounder of Richmond’s first interracial church council, he had no intention of letting recent surgery prevent him enjoying this moment. He paused to greet Rajmohan Gandhi, a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. Ten years earlier, as part of Richmond’s “honest conversation,” Taylor and Gandhi had addressed five hundred people from twenty countries and thirty U.S. cities on the grounds of Virginia’s State Capitol at the climax of an unprecedented walk through Richmond’s racial history.

In the ensuing years, Richmond’s private and public conversations on race shifted perceptibly. New relationships and partnerships began to span traditional boundaries. Gradually (nothing moves swiftly in Richmond) a citizen-led movement known as Hope in the Cities gained strength, creating an environment where tough public policy issues, previously “off-limits,” could be examined openly and without blame.

The gathering which brought Taylor and Gandhi to Tredegar would have seemed inconceivable when they spoke together a decade before. Even today many might look askance at the venue. The Tredegar Iron Works had produced more than one thousand cannon for the Confederate army during the Civil War. Without the industrial muscle of Tredegar, the South could not have sustained the long, brutal struggle that resulted in more American deaths than the two world wars, Vietnam, and Korea combined.

Many of those who labored here were industrial slaves, and in the early nineteenth century Richmond had grown wealthy as a center of the interregional slave trade that ripped families apart to provide male, female, and child workers for the new plantations in the Deep South. When the great conflict came, the Union and Confederate armies fought forty-three major battles within thirty miles of Richmond. Indeed it could be said that the ground of Virginia was soaked in the sweat and tears of slaves who strove for freedom and the blood of young white southerners who believed they were fighting in defense of their homeland.

After the war and Emancipation, black Richmonders experienced another bitter century of exclusion when a system of segregation replaced slavery throughout the southern states. Virginia led the movement of Massive Resistance against the integration of schools, and when change became inevitable, white Richmonders fled the city by the thousand. Wealth and poverty grew side by side in separate worlds. The interlocking walls of race, class, and political jurisdiction that bedevil many of America’s metropolitan regions came to define the limits of opportunity.

And yet here tonight, blacks and whites, city residents and suburbanites, recent immigrants and descendants of “first families,” grassroots activists and corporate executives, mingled as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

The chorus had swung into a Negro spiritual, “Walk Together Children, Don’t You Get Weary.” Ben Campbell, an Episcopal priest and urban visionary, took the stage to describe Richmond’s tortured history as a dark cloud hanging over the city. But a hope had been born in his heart that “the place where racism began in its worst form might be the place where healing can begin.”

He was joined by Michael Paul Williams, an African American columnist with the Richmond Times-Dispatch and a native Richmonder. He had seen his hometown evolve from a place that “discreetly oppressed its black citizens and where race was not discussed in polite company,” to a place where serious dialogue was occurring. The conversations had not always been calm or coherent, conceded Williams, but they had seldom been trivial. Richmond had struggled to “move the discussion from power, spoils and misguided nostalgia toward empathy, healing and a better tomorrow … to move from powerful symbolism to transformative change…. We have witnessed our politicians move from stark division and open rancor toward honest attempts to reach consensus.”2

Williams highlighted steps to reach a new, shared appreciation of history. As evidence, he noted the erection of a statue honoring the native-born African American tennis star and humanitarian Arthur Ashe on an avenue previously reserved for Confederate generals, and, most recently (and controversially), the honoring of Abraham Lincoln with a sculpture near the foundry. “Indeed,” concluded Williams, “anything is possible.”

Some of those present might have been surprised by the unequivocal nature of Williams’s statement, his evaluation of the dialogue that was taking root, and his affirmation of new relationships. Listeners might be impressed that a hard-nosed journalist could claim that a community still plagued by racial division, poverty, and violence was moving toward “transformative change.”

Williams was followed by two Virginians whose family stories illustrate the region’s tangled and painful history. Carmen Foster, a member of a distinguished African American family, had been executive assistant to Henry L. Marsh III, Richmond’s first African American mayor. It had been a turbulent time for the city. After centuries of white rule, a black majority won a majority of city council seats in 1977. “Confederate Capital Finally Falls to Blacks,” headlined the Afro-American newspaper. Richmond made national news as one of the first cities in America to elect a black mayor.

Opposition erupted when Marsh led the council in firing the highly capable but opinionated white city manager, an act that one business leader warned would cause blood to run in the streets. Since Richmond had long prided itself on its civility and had been spared the violence experienced by other U.S. cities in the 1960s and 1970s, this seemed unlikely; but the scene was set for several years of confrontational politics on a council which tended to vote along racial lines.

All this Carmen Foster had seen. In 1990, she left Richmond and headed north to attend graduate school, living in the Boston area for almost ten years. She hoped the move would fulfill a need to redefine herself outside the context of the black-white racial tensions of her hometown.

For a decade she lived and learned alongside Americans of every conceivable racial and ethnic background. She traveled in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. But although she relished her sojourn in Boston, she also discovered that racism comes in many flavors: “Whether it is southern-fried or northern-baked, it’s always bitter, hard to swallow, and the aftertaste lingers a long, long time.”

Now she was back in Richmond, and this evening she was escorted by her father, Dr. Francis Foster, a dentist and esteemed local historian. His grandfather was a slave named Jack Foster, the manservant of Christopher Tompkins, a Confederate colonel in the Civil War. After the war, Jack worked at Tredegar for its superintendent, Francis Glasgow. Jack married Virginia Taylor, the daughter of a slave woman and a local white merchant. They named their own son Christopher. When Jack died in 1897, the seventeen-year-old Christopher took over his father’s job as a messenger and porter. He can be seen today in a photo displayed at the old ironworks, standing with Francis Glasgow and Arthur Anderson, the foundry owner. Descendants of slaves like Jack Foster who worked at Tredegar after the Civil War helped build Richmond’s robust African American middle class.

Carmen remarked on the real differences she had seen since returning to Richmond a few years earlier, particularly “the honest dialogue about our past and our present which builds authentic relationships and challenges us to take responsibility for how we envision and craft our future.” She noted that however Richmond chose to reinvent its community life, “we stand on a collective past, a shared heritage, and interwoven roots.”

Standing beside Carmen Foster as she spoke was H. Alexander Wise, the great-great grandson of Henry Wise, the governor of Virginia who led his state out of the Union in 1861. He became a general in the southern army and, at the end of the war, surrendered, bitterly, to his own brother-in-law, General George Meade. One of his sons was killed in action, another wounded, and a third died of tuberculosis from sleeping on the wet fields.

Governor Henry Wise also reportedly fathered a son by a slave woman. That boy, William Henry Grey, became a prominent church leader and a politician in Arkansas at the time of Reconstruction, where he fought in vain for equality for his people.

Alex Wise’s family story illuminated the pain and sense of betrayal experienced differently by black and white southerners, which “hardened into racial resentments in our society that have lasted for generations.” But he said he had found a measure of freedom “in trying to imagine the world from the different viewpoints of William Henry Grey, of his mother, Elizabeth, of George Meade, as well as of Henry Wise.”

Carmen Foster, Alex Wise, and others in Richmond who have learned to appreciate each other’s stories as they work to heal racial history tread a delicate line. Such work, according to Donald Shriver, requires “a moral-historical discrimination not easily achieved by anyone white or black in modern America.”3 Empathy for individual courage and sacrifice must never imply sympathy for a heritage built on injustice: “Citizens need time to learn hospitality to each other’s feelings about their diverse, painful pasts…. But suffering itself, whatever its nature and circumstances, can evoke a communal bond.”4 This awareness informs Richmond’s reconciliation movement.

Wise described Tredegar as the future home of the first national Civil War center to tell all sides of a bitterly contested history. Through the center, everyone would be challenged to “walk in the other person’s shoes.” Tredegar might become a place first of dawning awareness, then of civil discussion, and finally of healing.

Wade in the water, children, sang the chorus, their conductor, Glen Mc-Cune, urging them on. In a city said to have more churches per capita than any other city of its size, it is rare to find blacks and whites worshipping together. One Voice, as the chorus is known, is distinguished by its unusual degree of racial integration and by its repertoire of sacred music from Western classical and African American spiritual traditions.

Glen McCune describes himself as a product of his time and culture: “I grew up in a poor white working-class environment near Shreveport, Louisiana, and I had never experienced any relationships in my life that were not bounded by Jim Crow.” A stint in the army in Germany provided the first window onto a wider world and his first experience with black Americans as equals.

For McCune, music became a road to redemption as “a recovering racist.” His arrival in Richmond was a surprise. “I had vowed I would never return to the South, and for thirty years I never did—except to visit my parents.”

One Voice is an apt metaphor for the community, says McCune. “The chorus is a resource for people who are pursuing the goal of reconciliation. Music penetrates hearts.” But it’s more than singing: “If we don’t infuse it with our stories, it will not be dynamic. When you invest your story and yourself when you are singing, your masks come down.”5

God’s gonna set this world on fire, sang the chorus, as colors exploded onto the screen behind them.

A mere hundred yards from the foundry, Abraham Lincoln is depicted seated on a bench in conversation with his son Tad. There is space on the bench for a visitor to join the conversation. Only seven months earlier, the sculpture had been unveiled in the wake of stormy public debate. So deeply did some southerners still feel their loss, so deep was their resentment of the North, that it took 140 years for America’s greatest president to find a home in Richmond.

Rajmohan Gandhi asked the crowd to imagine the challenge Lincoln—and his own grandfather Mahatma Gandhi—might have posed today. While praising Richmond’s progress, he suggested that the larger purpose was not merely the attainment of American unity, but the healing of a larger global divide: “After 9/11, which joined America to the suffering soil of the rest of our earth, Americans cannot afford to think only of uniting America—though, given today’s sharp divisions in the USA, that too is a vital goal. Americans certainly can do with honest and respectful conversations with one another. Yet after September 11, America, and all of us, have to strive to heal and unite the world, and for a just and lasting peace everywhere.”

Was it possible that a city divided by a cruel and violent history might, through courage and honesty and a willingness to forgive, become a source of hope and healing not only for America but for the world? This was the vision that Richmond celebrated tonight.

And then it was over. The choir sang the finale from Les Miserables. The crowd spilled out into the clear night with the lights of downtown to the east.

Earlier, Carmen Foster had described healing as hope and responsibility in action. Healing is about the future. The question is, “Do we really want to be well?” In 1993, a critical mass of Richmonders declared to the world that they wanted to be well. A decade later, on November 17, 2003, the affirmation at Tredegar reflected a community on the road to recovery.

![]()

2

Repairing the Levees of Trust

In a world of global cities, Richmond may seem relatively unimportant. With a center city of two hundred thousand and a metropolitan population of 1 million, it maintains a small-town atmosphere and a leisurely southern pace that has changed little over the years. Its economic prominence in the region has long been eclipsed by its southern cousins Atlanta and Charlotte. Newcomers from other cities tend to absorb the ambience rather than change it.

Richmond experiences the stresses of economic disparity, violent crime, uncontrolled suburban growth, and politi...