![]()

1Far from the Tree

Appropriations of Ethnic Memory and Other Frontier Encounters

The celebration of conquest typical of settlers in most colonized societies calls attention to the contestations and tensions between history and memory that reinscribed the wounding of those humiliated by colonization.1 In this chapter I read the oral tradition as much as I do the landscape and the colonial archive in order to tell the continuities and discontinuities of African history and memory before and during the moment of “permanent” colonial encounter. The chapter therefore offers a historical context for understanding how Black nationalistic imaginings of Charwe as Nehanda from the 1950s were not a first, but a mutation of a longer, if varied, history. It also shows that settler memory was keeping up the tradition of upholding the idea that the British Empire was still the mightiest—it could still occupy and conquer “Natives” elsewhere. Thus, rather than focusing on how nationalists “invented” the past, its heroines, and heroes wholesale, I am more interested in how they often embellished the bare bones of history with their nationalistic imaginations to create larger-than-life varieties of the originals.

First, the chapter briefly presents the legend of the “original” Nehanda and its mutations before 1890 to show how Charwe, the woman today famously known as Nehanda of Zimbabwe, was not the originator of the name or the title Nehanda.2 Also, Charwe was not the first Nehanda medium in the Mazowe valley, as detailed below. It is therefore important to keep in mind that Nehanda’s power (and that of her mediums) came from older African historical epistemology that understood the world as feminine, governed by forces of fertility in nature.3 Indeed, life itself was wrapped around the (goddesses or) female spirits that kept the cycles of life in balance.4 Second, this chapter shows how history and memory circled each other during the frontier war of 1896–97 in Southern Rhodesia, when settlers consciously and unconsciously erected real and symbolic sites of imperial memory on African landscapes in the Mazowe valley and elsewhere in the colony. History was being made on a landscape once sacred to some, now a new site of memory for others. The frontier war fought on that landscape simultaneously raised monuments to imperialism, while forgetting the history of Africans who had lived there centuries before.

The Original Nehanda, Nyamhita Nyakasikana, and Other Nehandas of Mazowe

Thirty miles north of Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, is a valley of rugged mountains and fertile land that has attracted generations of wanderers in search of secure water patterns and rich soil that could enable their agrarian societies to thrive. The current people claiming autochthony (original settlement and land ownership) are descendants of the northern Hera people, a confederacy of dynasties founded by two brothers and a nephew—Gutsa, Shayachimwe, and Nyamhangambiri. As in the kinship systems of most Niger Congo peoples, a highly structured kinship was remembered and maintained through a sophisticated totem (mutupo) narrative that served political, social, cultural, and economic functions, including practical ones like specifying who could marry whom to avoid incest.5

Charwe was born about 1862 of the Hwata people in the Mazowe valley, a dynasty founded by Shayachimwe.6 Like many young girls of her time, Charwe grew up, got married, and had children. Things changed at the peak of her womanhood, when she became the medium of the spirit of Nehanda, a revered spirit of rain and land fertility among northern, central, and eastern peoples we call the Shona today.7 To be a medium of the spirit of Nehanda, therefore, was to hold a position of significant religious and political power in an agrarian society in which life revolved around the seasons of earth and sky. Once Charwe became a medium of a significant female spirit, she followed in the footsteps of other women of the Mazowe valley who had held that politico-religious office, which afforded them a social and economic status not available to many women. The prestige came from being the gombwe (superior, or senior, medium) of a mhondoro (royal lion spirit) of an old dynasty’s founding mother or father. Mhondoro were prestigious spirits, and their mediums, whether female or male, were treated like royalty. Being a gombwe was therefore different from the “common” mediumship (svikiro) of familial and local clan spirits.

Oral traditions and archaeological evidence suggest that among the Shona, mediumship of human spirits was a religious experience confined to familial and clan structures.8 It turned into public office as family groups and clans settled and grew into larger ethnic groups of different families and clans, creating dynasties and kingdoms-cum-nations that aspired to legitimate their political and economic power, reminiscent of small empires. Among the Shona in older times, both women and men were revered and remembered by the living as founding ancestors in totemic praise poems and songs.9 The dead, as royal (or ordinary) ancestors, were believed to make their presence tangibly felt through spirit mediums, people so chosen by the dead spirits. The dead, it was believed, chose their mediums without interference from the living, and those mediums were accepted through an authentication process administered by long-practicing and respected mediums. Once confirmed, the medium acquired gravitas that could not be nullified by the living; only the spirit could nullify that position by choosing another medium, which usually meant the (premature) death of the current medium. The reality, as we will see, was a little more complicated than that, for spirit mediumship, like all human institutions accredited with the power of the (dead and) beyond, was as human as it was said to be divine.

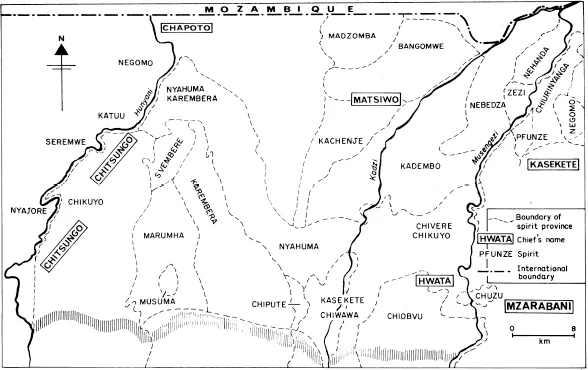

One oral tradition of the history of Nehanda Nyamhita Nyakasikana, the original Nehanda, tells that she hailed from northeastern Mashonaland.10 Nyamhita’s mother and brother, the tradition says, had her participate in the dynastic ritual kupinga pasi, laying claim to the land through ritual incest, against her will.11 She was appalled by what had happened, and rather than stay in Dande, in her territory, known as Handa (see figure 1), she vanished into a small hill and was later reported as living south of her territory. It is worth noting at this point that the etymology of Nehanda is a geographic location in Dande named Handa. The article Ne is the honorific possessive denoting ownership (of territory or otherwise) in central and northeastern MaShonaland, therefore, Ne = (owner) of Handa (in other Shona regions people use the articles Va or Wa or Nya, hence some colonial spellings that use Nyahanda, Neanda, Nianda, or Nyanda for Nehanda). Indeed, the name Nehanda makes a compelling little piece of history of a term that in memory means a person, when its origin meant a place, a (sacred) site of memory on a hill.

Figure 1. “Original” Nehanda territory, shown in the top righthand corner. (Lan, Guns and Rain, 33, with permission from the University of California Press)

To this day, the oral tradition continues: the hill in Handa bears the imprint of Nyamhita’s disappearance and is called Gumbi ra Nehanda. After she died, her spirit split into two: The first was Musuro wa Nehanda (Nehanda’s Head), a spirit that remained active within Dande ensuring the continued fertility and vitality of that region as well as retaining a place of sociopolitical and cultural power in society for women who were its mediums. The second spirit, Makumbo a Nehanda (Nehanda’s Feet), manifested in the south among the people of the Gumbo dynasty, near Domboshawa, where she had settled. By the time Nyamhita died, she was venerated by many in that dynasty and region of central Mashonaland, including Mazowe and Chishawasha—important sites of history and memory in this book. She was known by many as their Ambuya (ancestor), a great rainmaking spirit, a spirit of fertility (human and otherwise).12 The Gumbo dynasty later moved further south into what is now Gutu (Masvingo Province), and their former area, near Domboshawa (central Mashonaland), was settled by the Hwata dynasty, among whom Charwe was born. Interestingly, it seems that the second spirit of Nehanda, Nehanda’s Feet, not only stayed in the Domboshawa area but also became part of the Hwata dynasty’s own history and memory of belonging to a land the dynasty had just settled, having emigrated from VuHera (now Buhera), an area to the southeast. Paradoxically, the Gumbo took the tradition of the spirit of Nehanda with them to Gutu—which makes sense, for who would not want such a spirit of rain and fertility as they migrated in search of better lands and opportunities? That may explain why around the Great Zimbabwe (also in Masvingo Province) there has been a (contested) tradition of a Nehanda or Nehandas, some recently documented by the anthropologist Joost Fontein in his ethnography of communities in the area.13

The spirit of Nehanda and its mediums, as highlighted above, is a history that captures both the history of a woman who once lived (Nyamhita) and the memory of a spirit (Nehanda) still circulating among the living in memory through its female mediums not only in its original place but also in multiple sites around Zimbabwe. In a way, Nyamhita’s history as Nehanda is a compressed history of religions that, like all religions, are “manifestly cultural products . . . [that] serve human and cultural ends.”14 Nyamhita, then, may be translated into an unsatisfying (and some will say false) analogy of a Jesus who became the Christ or a Siddhartha who became the Buddha. That is, Nyamhita’s life may have radically changed gender, class, and ethnic realities in her society such that other women wanted to be her mediums—if not to be her.15

I chose the historian David P. Abraham’s rendition of the Nehanda oral tradition not only because its content is rich in detail and has an ear toward memory told as history but also because it closely resembles some of the histories and traditions recorded by the Portuguese from the mid-1500s about women’s place in the African societies they encountered in southern Africa.16 Thus, though there is no definitive version, oral or written, of who Nyamhita was and how her spirit as Nehanda moved from the Dande valley to the Mazowe valley, it is indisputable that the name Nehanda still has resonances in both, as well as around Zimbabwe. The fruit of Nehanda’s memory certainly fell far from its original tree, and wherever it fell, it adapted to its new environment—much as Christianity did over time and space. That memory of Nehanda was the power transferred to Charwe, as medium, when the British arrived on the scene in the Mazowe valley in the late nineteenth century. Thus, by the time Charwe started practicing her mediumship in the mid-1880s, the name and tradition of Nehanda was well established in the Mazowe valley thanks to several mediums who had preceded Charwe, perhaps since the early eighteenth century, such that the place was known as Nehanda’s.

The recorded mediums of Nehanda in the Mazoe valley immediately before and after Charwe were Chamunga, Damukwa, Chizani, Charwe (ca. 1862–1898), Mativirira, and Mushonga.17 The British traveler Walter Montagu Kerr, who passed through those lands in 1884–85, wrote that he saw in the distance “a chain of craggy mountains, stark upheavals spirelike rocks whose wild recess concealed Neanda, a large Mashona town.”18 Among those “craggy mountains” was the sacred Shavarunzi, at which Nehanda mediums of Mazowe practiced; and when they died, they were often buried there. Thus, Shavarunzi was a sacred site for rituals of rainmaking. It was also a site of memory, because of the Nehanda mediums buried there. The burial of those women on that mountain had particular significance because among the Shona, dynasty founders, kings, and chiefs were buried in mountain caves, making their burial sites important places of remembrance and pilgrimage for their descendants and those who believed in their powers to heal, guide, and bring about rain and prosperity. Shavarunzi’s status as a site of memory was equivalent to that of many old and new religious sites considered sacred in other cultures and traditions, for example, the Bodhi Tree in India, the “Holy Land” in the Middle East, or Wounded Knee in South Dakota.19 Burial on Shavarunzi accorded very few women significant status in a society in which most women had lost or were losing power and influence, except in positions like mediumship of founding or royal spirits. In memory, however, Charwe became the one and only Nehanda. The Mazowe valley, not the Dande valley, became the new site of memory associated with the power of Nehanda in postcolonial Zimbabwe.20

The spirit of the legendary Nehanda-Nyamhita—the spirit of rain and fertility—as represented by its mediums, also called Nehanda, may have been the initial focus of African nationalists in their fight against colonialism, as illustrated by David Lan’s ethnography Guns and Rain. However, unlike Lan’s study, this book focuses entirely on nationalists’ imagined Nehanda, transfigured into the warrior woman Charwe to fit the “modern” reality of a guerilla-cum-nationalist movement seeking relevance. By focusing on the history and memory of Charwe in her own right—rather than on Nyamhita and Charwe, as Lan did—this book calls attention to the importance of studying Charwe’s life and legacy in nationalist thought and ideas that shaped a sense of ownership of the “new” nation, Zimbabwe, at independence in 1980. Thus, rather than treading and recycling the same ideas expounded upon by scholars such as Terence Ranger, David Beach, David Lan, and David Martin and Phyllis Johnson, among others, I move the historiography forward by centering Charwe’s importance in nationalist thinking and claiming Rhodesia as Zimbabwe, a Black nation. I ask: How did Charwe become people’s anchor as they tried to turn individual, social, and collective African history into a useable memory to claim a right to citizenship in a nation constituted without their participation and consent in Berlin in 1884–85?21 Despite nationalist rhetoric, this book insists that the contested Rhodesia that was to become Zimbabwe did not exist in that shape or form prior to 1890. By positioning Charwe at the center of white and black nationalist discourse, we can name the vandalism of British colonialism, while asking why the nation has become the category, rather than a question, in the historical analysis of African history.

Gendered Occupation and Its Contestations

The Mazowe valley came into the purview and control of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, as Portuguese power was waning in western Europe and globally.22 The hold-your-nose-as-you-pass-by attitude toward the Cape Colony on the part of the British and most western European powers racing for the Far East changed in 1867 when a gleaming stone that turned out to be a twenty-one-carat diamond was found along the Orange River. March 1869 turned up an even more fantastic find, an eighty-three-carat diamond, and by the 1870s the diamond rush was in full swing (fig. 2). In the field of competition that was the diamond rush was a young man by the name of Cecil John Rhodes (later known t...