- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

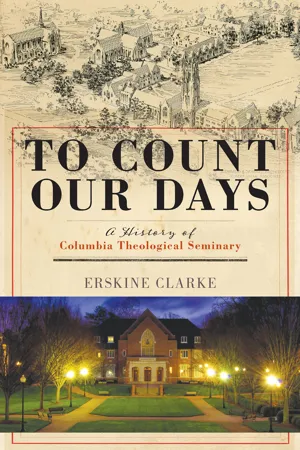

About this book

An in-depth look at the institution as the center of many important cultural shifts with which the South and the wider Church have wrestled historically.

Columbia Theological Seminary's rich history provides a window into the social and intellectual life of the American South. Founded in 1828 as a Presbyterian seminary for the preparation of well-educated, mannerly ministers, it was located during its first one hundred years in Columbia, South Carolina. During the antebellum period, it was known for its affluent and intellectually sophisticated board, faculty, and students. Its leaders sought to follow a middle way on the great intellectual and social issues of the day, including slavery. Columbia's leaders, Unionists until the election of Lincoln, became ardent supporters of the Confederacy. While the seminary survived the burning of the city in 1865, it was left impoverished and poorly situated to meet the challenges of the modern world. Nevertheless, the seminary entered a serious debate about Darwinism. Professor James Woodrow, uncle of Woodrow Wilson, advocated a modest Darwinism, but reactionary forces led the seminary into a growing provincialism and intellectual isolation.

In 1928 the seminary moved to metropolitan Atlanta signifying a transition from the Old South toward the New (mercantile) South. The seminary brought to its handsome new campus the theological commitments and racist assumptions that had long marked it. Under the leadership of James McDowell Richards, Columbia struggled against its poverty, provincialism, and deeply embedded racism. By the final decade of the twentieth century, Columbia had become one of the most highly endowed seminaries in the country, had internationally recognized faculty, and had students from all over the world and many Christian denominations.

By the early years of the twenty-first century, Columbia had embraced a broad diversity in faculty and students. Columbia's evolution has challenged assumptions about what it means to be Presbyterian, southern, and American, as the seminary continues its primary mission of providing the church a learned ministry.

"A well written and carefully documented history not only of Columbia Theological Seminary, but also of the interplay among culture, theology, and theological institutions. This is necessary reading for anyone seeking to discern the future of theological education in the twenty-first century." —Justo L. González, Church Historian, Decatur, GA

"Clarke's engaging history of one institution is also an incisive study of change in Southern culture. This is institutional history at its best. Clarke takes us inside a school of theology but also lets us feel the outside forces always pressing in on it, and he writes with the skill of a novelist. A remarkable accomplishment." —E. Brooks Holifield, Emory University

Columbia Theological Seminary's rich history provides a window into the social and intellectual life of the American South. Founded in 1828 as a Presbyterian seminary for the preparation of well-educated, mannerly ministers, it was located during its first one hundred years in Columbia, South Carolina. During the antebellum period, it was known for its affluent and intellectually sophisticated board, faculty, and students. Its leaders sought to follow a middle way on the great intellectual and social issues of the day, including slavery. Columbia's leaders, Unionists until the election of Lincoln, became ardent supporters of the Confederacy. While the seminary survived the burning of the city in 1865, it was left impoverished and poorly situated to meet the challenges of the modern world. Nevertheless, the seminary entered a serious debate about Darwinism. Professor James Woodrow, uncle of Woodrow Wilson, advocated a modest Darwinism, but reactionary forces led the seminary into a growing provincialism and intellectual isolation.

In 1928 the seminary moved to metropolitan Atlanta signifying a transition from the Old South toward the New (mercantile) South. The seminary brought to its handsome new campus the theological commitments and racist assumptions that had long marked it. Under the leadership of James McDowell Richards, Columbia struggled against its poverty, provincialism, and deeply embedded racism. By the final decade of the twentieth century, Columbia had become one of the most highly endowed seminaries in the country, had internationally recognized faculty, and had students from all over the world and many Christian denominations.

By the early years of the twenty-first century, Columbia had embraced a broad diversity in faculty and students. Columbia's evolution has challenged assumptions about what it means to be Presbyterian, southern, and American, as the seminary continues its primary mission of providing the church a learned ministry.

"A well written and carefully documented history not only of Columbia Theological Seminary, but also of the interplay among culture, theology, and theological institutions. This is necessary reading for anyone seeking to discern the future of theological education in the twenty-first century." —Justo L. González, Church Historian, Decatur, GA

"Clarke's engaging history of one institution is also an incisive study of change in Southern culture. This is institutional history at its best. Clarke takes us inside a school of theology but also lets us feel the outside forces always pressing in on it, and he writes with the skill of a novelist. A remarkable accomplishment." —E. Brooks Holifield, Emory University

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

An Antebellum World

1

Beginnings

In 1822 the Reverend Thomas Goulding announced to his Georgia congregation of white planters and black slaves that he was moving. He hoped, he said, that a change of location would help him recover his health. Repeated bouts of malaria—country fever he called it—had wracked his body and had left him largely debilitated. Goulding resigned as pastor of the White Bluff Presbyterian Church, near Savannah, and reported that he had bought a small farm in Oglethorpe County in northeast Georgia. There among rolling hills and hardwood forests he hoped to escape recurrent bouts of the fever and regain his health and strength.1

When Goulding left White Bluff for his newly purchased farm, he took with him his wife, Ann Holbrook of Connecticut, four children, and six slaves. On the arduous journey inland, Goulding also carried with him an experience of theological education as it had been practiced by Presbyterian pastors in colonial America and in the young republic. What he did not know was that ahead of him was not only a farm but also an important role in the establishment of something new that was beginning to emerge in American religious life—a southern theological seminary.2

Thomas Goulding had been born in 1786 on his father’s plantation in Liberty County, Georgia, where black rivers flowed slowly out of cypress swamps into St. Catherine Sound. This landscape and the social arrangements of white owners and black slaves shaped and informed young Goulding’s earliest memories and the deep assumptions and dispositions that he would carry for the rest of his life. When he was eighteen he left his plantation home and made his way to New Haven, Connecticut, to enter Yale College. On his arrival in New Haven, however, he found a system of hazing had recently been established by older students. Unwilling to be a servant to anyone, he refused to join his class. Instead he began to study law with a local judge while still enjoying some of the privileges of the college. In 1806 he married Ann Holbrook and shortly thereafter returned to Georgia, where he taught the sons and daughters of Georgia planters at two academies, both of which looked out over marshes to the distant Sea Islands and their plantations.3

While Goulding was busy with his teaching responsibilities, a religious awakening was spreading across the young republic, and in time it began to penetrate the plantation communities of the Georgia coast. Goulding began to struggle with his own religious feelings, hoping that the Spirit of the Lord would touch his heart and awaken him to God’s grace and love in his own life. He had, he later reported, a strange conversion experience—it happened while he slept. Wearied, he said, with his burden of sin and his fruitless search to find a savior, he sank despairingly into a profound slumber and awoke praising God for his great salvation. Shortly thereafter he began to prepare for the ministry in the way earlier generations of American Presbyterian ministers had been prepared—he began an intense course of study under the direction of other ministers. In 1811 Harmony Presbytery took him under its care as a candidate for the ministry to guide him in his preparation. After two years of study, he was licensed by the presbytery and began a trial period as stated supply of the White Bluff congregation. After another three years, he was finally ordained and installed as pastor of the congregation. During this time he proved himself to be a serious scholar, and in a few years the University of North Carolina honored him with the degree of doctor of divinity.4

When Goulding arrived in Oglethorpe County in 1822 with his family and slaves, he found a young community that was growing rapidly. A new cotton kingdom was pushing westward, bringing with it not only whites eager for land and profits but also massive numbers of slaves being uprooted from seaboard areas and carried to rich new lands in the interior. Within three decades of Goulding’s arrival on his farm, over seventy-eight hundred slaves would be chopping and picking cotton in the county.5

Among the newcomers to the county were farmers from the upcountry of South Carolina. They were largely descendants of Scotch Irish immigrants who had arrived in Philadelphia during the colonial period and had traveled south on the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road that ran from Pennsylvania through the Shenandoah Valley into the Catawba River valley and on to Augusta, Georgia. In South Carolina they spread over the upcountry, where they cut small farms out of the wilderness, organized Presbyterian churches after the pattern of the Church of Scotland, and slowly began to establish schools. When upcountry settlers moved into Oglethorpe County, they, together with settlers from the lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia, began to create cotton plantations, some of which soon became large and prosperous. Two years after his arrival in the county, Goulding left his small farm and moved into the little village of Lexington, where he became pastor of the newly organized Presbyterian church and a teacher in an academy for the children of planters in the region. He soon became a leader in an effort to establish a “Literary and Theological Seminary for the South.”6

Presbyterian leaders—clergy and lay—were eager to establish an institution that would serve the educational needs of the church and society in the Lower South with its expanding frontier. A board of directors was organized to pursue this objective, and Goulding was elected a member. At first they hoped for a college with a theological seminary attached. They purchased land near Pendleton, South Carolina, and began a vigorous fund-raising effort. But soon questions began to be raised. Did Presbyterians need to establish a college in the upcountry? They already largely controlled Franklin College in Athens (later to be the University of Georgia), and while the South Carolina College in Columbia was suspect because of the supposed infidel leanings of some of its faculty, it was a prestigious institution with an impressive library. After long debates in the Synod of South Carolina and Georgia, and many committee meetings, the synod decided to drop the idea of a college and to establish a freestanding theological seminary. Both Athens and Columbia were proposed as the site of the new seminary. The synod selected Columbia.7

Beneath the synod’s desire for a theological seminary were revival fires that had been sweeping over the country since the beginning of the nineteenth century. Goulding’s conversion had been part of a general religious awakening—a Second Great Awakening, which followed a First Great Awakening during the colonial period. The awakening had been not only warming individual hearts but also spawning a rapidly increasing number of churches and benevolent societies. The demand for ministers was consequently intensifying, especially to meet the challenge of an expanding frontier and the rising call of foreign missions. More was needed than the kind of preparation Goulding had received when he went to live with mentoring pastors in “household schools.” At the same time, an increasing secularization of collegiate education was turning many colleges away from an older classics curriculum—which had been largely designed for the education of ministers—toward a new emphasis on the sciences and legal subjects. Church leaders, left uneasy by such shifts, began to search for alternatives. Congregationalists in Massachusetts led the way when they established Andover Theological Seminary in 1808.8

Andover’s founders wanted an institution of the church for the professional education of ministers. Moreover they believed that a theological seminary would be the means of nurturing and transmitting a theological tradition, of responding to theological controversies, and of advancing sectional and ideological interests. Columbia’s founders had the same hopes for their southern Presbyterian theological seminary.9

Andover set the institutional character of the seminaries that would soon be established across the country—a graduate professional institution with a full-time faculty, capital funds and a campus, a library, a resident student body, a three-year curriculum, and a board of directors. The requirement of a bachelor of arts degree, although not always maintained, was intended to ensure that theological students had both the philosophical and linguistic background provided by a collegiate education and—not incidentally—the general culture and manners taught in the colleges.10

Not all denominations, however, welcomed the arrival of theological seminaries. The Second Great Awakening had a powerful egalitarian thrust and released a democratic spirit that invited the pious, even the most unlearned, to preach. The Baptists were calling “farmer preachers,” godly men known to congregations, to plow their farms during the week and sow the Word on the Sabbath. In this way Baptist congregations were spreading rapidly, especially across a southern frontier that was already reaching into Alabama and Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. But Methodists were the most prominent of a host of opponents to seminaries or “priest factories.” For the Methodists a seminary education threatened to “dry up the sparks of the Holy Spirit” and separate the clergy from the laity in an elitist fashion. Perhaps ironically the Methodists would in time become the primary sponsors of university-related divinity schools where secular and religious leaders would be educated in single institutions.11

In December 1828 the synod elected Goulding professor of theology and gave him permission to remain in Lexington as plans were developed for the establishment of the seminary in Columbia. Five students came to Lexington and, after the old pattern, began their study for the ministry in the Lexington manse. While their work was preparatory for a full course of theological education, their arrival in Lexington in 1829 marked the founding moment for the seminary. In January 1830 Goulding with his family and slaves, together with his little clutch of students, moved to Columbia and occupied the former manse of the Presbyterian church in the city. Plans were already underway for an impressive new campus.12

Colonel Abraham Blanding, a prominent Presbyterian, had raised the handsome sum of $8,000 from members of several denominations in Columbia. He had then proceeded, with an additional mortgage of $6,000, to purchase the magnificent Ainsley Hall mansion and to offer it with the mortgage to the synod.

Ainsley Hall, an immigrant from the north of England, had made a fortune with his cotton and general merchandise business as the little town of Columbia expanded following its establishment in the late 1780s. By 1810 Hall was also raising cotton on several plantations scattered across the central portion of the state. In 1818 Hall moved his family into a new mansion he had built on a four-acre town lot. Six years later Wade Hampton I, already one of the wealthiest men in the nation, rode in from his country estate and asked Hall to name his price for the house. Hampton wanted immediate occupancy, and when Hall named the princely sum of $37,000, Hampton bought the house, complete with its elegant furniture. Hampton could easily afford the price. He owned plantations not only in South Carolina but also in Mississippi and in Louisiana, where his plantations made him the largest sugar producer in the state. At the time of his purchase of the Hall mansion, Hampton owned almost one thousand slaves.13

Hall then purchased a four-acre track immediately across the street from his former home and hired the architect Robert Mills to design a handsome new mansion. Mills, a member of the Presbyterian church in the city, had already established a reputation as one of the nation’s leading architects. He had worked with his mentor James Hoban on the construction of the White House and he would himself design many of Washington’s most famous buildings. When he began work on the new Ainsley Hall mansion, he was already responsible for helping to set a classical style for many of the nation’s public buildings. Later he would be best known as the architect of the Washington Monument.14

Mills designed a classical brick mansion for Ainsley Hall. Every aspect of the building said to passersby and visitors, “Look, here is the home of wealth and influence!” Two stories rose high over an elevated, first-level basement. A front gate acted as a threshold and entrance into an expansive landscape, and a walk led a visitor to wide and imposing steps that climbed to the second level of the house. There a brick arcade provided a porch for the main entrance, and on the arcade stood four massive columns that made of the porch an Ionic-temple portico. The front door, handsome in its detail, faced north and looked competitively across the street to the Hampton mansion. Going through the door, a visitor entered a large rectangular hall and the world of the mansion.15

It was this handsome mansion that Colonel Blanding purchased for the new theological seminary. But the mansion was not the only building on the lot. An unpretentious house—a story and a half—had been built for domestic slaves who were to do the cooking and washing and cleaning for the white owner. And on the other side of the lot was another unpretentious house built for the family of a slave gardener who was to spread sand on the walks, tend the flower beds, and plant azaleas, camellias, and sweet-smelling tea olives. The elegant design of the Ainsley Hall mansion, together with its slave quarters and its location across the street from the Hampton mansion, pointed not only to the physical character and social location of the new seminary, but also to important elements in the seminary’s character and purpose. Blanding, in a letter to the board of directors, said that those who had contributed to the purchase of the mansion and its outbuildings had as their object the establishment of “a Southern theological seminary.” And the synod itself had noted earlier the distinctive habits and feelings of southerners on many subjects and “other circumstances that need not now be particularly detailed.” The synod meant, of course, the distinctive habits and feelings of white southerners. Those habits and feelings, the synod declared, made the establishment of the seminary “of vital importance to the Southern Church.” The seminary was to be an institution serving “Our Southern Zion.” In this way the Ainsley Hall mansion represented an embodiment of the theological commitments and ideological interests of South Carolina and Georgia Presbyterians. Columbia was to be an elite institution of higher education to prepare ministers for a rapidly growing church. It was to be a center for the most serious theological reflection advocating and defending a Calvinist tradition. And it was to provide an ideological undergirding to a southern way of life—it was to help hide the harsh realities of slavery and to help legitimize the power and wealth of slave owners and the social order that kept them powerful and wealthy.16

The selection of such a building for the new seminary echoed the world of its board of directors. Benjamin Morgan Palmer Sr., president of the board, was the pastor of the Circular Congregational Church in Charleston, whose magnificent sanctuary had also been designed by Robert Mills. During the first decade of the seminary’s history, the congregation included among many distinguished Charlestonians U.S. senator Robert Young Hayne, Congressman Henry Laurens Pinckney, and U.S. attorney general Hugh Swinton Legaré. Other ministers on the board included those from affluent country congregations made up of white planter families and many slaves—Elipha White from Johns Island, south of Charleston; John Cousar and Robert James from the Sumter District of South Carolina, where cotton was turning farmers into wealthy planters; and Horace Pratt from the little village of St. Mary’s in the midst of Georgia’s great rice and Sea Island cotton plantations.17

The Presbyterian minister Moses Waddell brought to the board a long career as an educator. He had recently retired as president of Franklin College (University of Georgia) and had earlier been the far-famed educator at his Willington Academy in the upcountry of South Carolina. He had taught a generation of southern leaders—most famously John C. Calhoun. By the end of the antebellum period, his former students would include two U.S. vice presidents, three secretaries of state, three secretaries of war, one U.S. attorney general, ministers to France, Spain and Russia, one U.S. Supreme Court justice, eleven governors, seven U.S. senators, and thirty-two members of the U.S. House of Representatives—to enumerate only the political leaders! Waddell emphasized a strict classic education, and his students were expected to recite Horace, Livy, and Cicero in Latin, and Homer, Herodotus, and Thucydides in Greek.18

The vice president of the board for the first years of seminary’s life was John Taylor, former U.S. congressman, senator, and South Carolina governor. A strong s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: An Antebellum World

- Part II: A Southern Horizon

- Part III: A Seminary for the New South

- Part IV: New Horizons

- Epilogue

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Subject Index

- Index of People

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access To Count Our Days by Erskine Clarke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.