![]()

1

Russel and Mary Wright: Nostalgic Modern and the “American Way of Life”

There are many Americans who still enjoy or remember eating off a plate from Russel1 and Mary Wright’s American Modern china collection. The dinnerware’s beautiful sculptural forms, interesting colors, and simplicity graced many a dinner table in the mid-century period. Moderately priced, well designed, fun yet sensible, these Wright designs became one of the hallmarks of the modern, more informal “new American way of life” that the couple helped create and promote. But American Modern dinnerware was just a small part of the Wrights’ total oeuvre and their life-long efforts to bring modern design to Americans by creating a specifically American approach to design. To that end, the couple built on the work of their predecessors, Frank Lloyd Wright and the American Arts and Crafts movement, and used interior design as a medium to systematically design or direct the careful choice and placement of all items needed for an appropriately American modern home. They documented this strategy in their popular book Guide to Easier Living (1950), which gave extensive directions for house planning, buying furniture, and housekeeping procedures. At the root of these efforts and embedded in all their work was the couple’s underlying concern, if not fixation, about how design could and should be used to express American character and values.2 The trajectory of this concern is a long but consistent theme that runs through the Wrights’ careers, and from early on ideas about patriotism and American identity were embedded in the Wrights’ work, especially in their approach to interior design. These were promulgated in their Guide to Easier Living and in the designs of their own highly publicized homes, supporting them toward their goal of providing an alternative to European modernism and an appropriately American kind of modern interior design.

Early explorations

Russel and Mary Wright were not trained as designers but came to the practice from backgrounds in art and theater. Russel Wright, a native Ohioan, was the son of a judge who claimed an illustrious pedigree as a descendant of American Quakers and signers of the Declaration of Independence. Although encouraged to a career in law, his father’s profession, Wright began taking art classes at the Cincinnati Academy of Art while still in high school. After he graduated, he continued that study at the Art Students League in New York City for a year before entering Princeton in the fall of 1921. Although he had agreed to begin to study law at Princeton, he soon left it behind to investigate the college’s theater program as an outlet for his creativity. He joined the Triangle Club, the theater’s support group, and designed sets and directed plays while working on his degree. In the summer of 1923 he lived in Woodstock, New York, and worked at the well-known Maverick Art Colony on its annual theatrical festival designing sets and props. He returned to Princeton in the fall but spent his weekends in New York City working in the theater there. In 1924, he left school to dedicate all his time to that avocation. There, he soon met set designer Aline Bernstein (later mistress to Thomas Wolfe), who became a close friend and mentor and who helped him find various jobs in the theater in the late ’20s, including positions at the Neighborhood Playhouse and Laboratory Theatre in New York. In 1927, Wright returned to Woodstock to work again in the Maverick Theater where he met his future wife, Mary Small Einstein, the daughter of a wealthy, socially established family and a distant relative of the famous Albert Einstein. Mary Einstein was a native of New York City, and when she met Wright, she was studying sculpture with the European artist Alexander Archipenko at his summer workshop in Woodstock. Against her family’s wishes Einstein married Wright in 1927. The couple lived in Rochester, New York, for a short time while Wright was the stage manager of George Cukor’s theater company, but they soon moved back to New York City where they continued to live for most of their lives.

The transition for Russel Wright from theater to industrial design was a common course of action during the late ’20s and ’30s as the entrepreneurial spirit that rose out of the stock market crash and subsequent Great Depression encouraged the growth of this new design field. The 1933 and 1939 World’s Fairs, with their emphasis on technology and the future, added to this impetus. Leaders in the burgeoning field of industrial design such as Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy, and Joseph Urban, who helped create futuristic visions for these events, all became successful product, furniture, and interior designers by building on their careers and reputations made in theater design. Theater historian Christopher Innes notes:

That this transfer from theater to industrial and architectural design was possible is partly due to the way America prided itself on being the new world, liberated from the hierarchical traditions of European empires. This made it more acceptable for people to cross over from one specialization to another. American industrialists looking for designers to create mansions that would display their status … liked what they saw on Broadway and sought out stage designers for the job. (Innes 2005: 15)

Russel Wright had apprenticed with Bel Geddes when he was working as a set designer in New York and was well aware of this trend. The Wrights saw the opportunity in this wave of interest and excitement about industrial design and began their work as a team by designing and promoting numerous products for in-home use in the 1930s such as their successful Informal Accessories line of aluminum cocktail sets, cups and ice buckets, and other products. While Russel Wright was the primary designer in these efforts, Mary Wright’s history and experience with her family’s successful textile manufacturing concern gave her a unique understanding of business and of how to market and promote not only their products but themselves as designers. She organized the production, distribution, and sales for all Russel Wright–designed products until her death in 1952. It was her business acumen and energy that pushed her husband’s designs in the 1930s to the forefront and provided him with name recognition throughout the United States. Wright biographer William Hennessey says that Mary Wright “must be given credit for a good deal for the work’s popular success. Her business sense, as well as her New York social connections and financial resources were of vital importance in getting the design business started” (Hennessey 1983: 23). Although it was Russel Wright’s name that went on most of the products and projects, Mary is considered here as a full partner and given credit alongside Russel for all the Wrights’ accomplishments in creating modern American design.

American Modern

By the late 1930s, the Wrights became focused on the goal of creating design that expressed specifically American values. The rising popularity of European modernism in the United States and its promotion by manufacturers, department stores, and institutions, such as the Museum of Modern art and others, became something that they began to see as a threat to American design. They became passionately inspired and motivated to “help rid this country of its great Art-inferiority-Complex” (Albrecht, Schonfeld, and Shapiro 2001: 17) and to create a distinctly American identity for design free from European influences. As their daughter, Ann Wright, related in her preface to the 2001 publication, Russel Wright: Good Design Is for Everyone:

In fact, it was not until I was nine or ten that I even understood there was a “European Style” From my point of view, there was only “Russel Wright Style,” which is what we lived and what the rest of the world ought to live, if they didn’t already. (Albrecht et al. 2001: 17)

The Wrights’ preoccupation with establishing a distinctly American identity was something they shared with many groups of people. Christopher Innes notes that it was a consistent theme and impetus in the theater world as Americans searched for a “real” national identity aligned with the modern world, and that popular catchphrases such as “the American dream” and “the American way of life” became so standard that in 1939 Kaufman and Hart used “The American Way” as the title for one of their Broadway comedies. Set designers turned product and interior designers such as Joseph Urban and Russel Wright grasped the excitement and creative potential of this moment. Innes says that Urban

was struck by the new conditions he saw around him. He saw that the modern world, emerging so energetically and chaotically in this young and bustling nation, needed its own mode of expression … traditional styles, which were still being applied haphazardly across America, would not do. Nor would the new European design principles … None of these reflected the American experience. (Innes 2005: 2)

The Wrights’ and Urban’s concerns reflected a trend that had been gaining ground in the United States since the early part of the twentieth century. Historian Michael Kammen points out in his extensive work, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (1991), how a “general and country-wide revival of Americanism” followed the defeat of “Woodrow Wilson’s universal idealism” after the end of the First World War. He says that books such as novelist and cultural critic Waldo Frank’s Our America of 1919 (serialized for the New Republic in 1927–1928 as The Re-Discovery of America: An Introduction to a Philosophy) as well as historian Stuart Pratt Sherman’s essay “The Emotional Discovery of America” (1925) marked the beginning of a trend to “explore and expound upon American tradition.” Kammen concludes that “the emotional discovery that took place during the 1920’s produced a vulgate of American exceptionalism never before known. The phrase ‘strictly American’ popped up boastfully throughout the country” (Kammen 1991: 303). With this impetus, in the ’20s and ’30s the quest not only to create but also to preserve American traditions came to the foreground.

While poet Stephen Vincent Benét, composer Aaron Copland, and artist Thomas Hart Benton were attempting to create their own distinctly American art forms, connoisseurs and collectors such as Henry Ford and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller made the collection and preservation of American traditional arts a new American initiative. While transforming the world with the modern technology of the automobile, Henry Ford became particularly enamored with preserving the American past and its distinct character. Ford began collecting Americana in the early 1920s and soon compiled one of the most comprehensive collections in the United States. In 1922, he purchased the Colonial-era Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts, to preserve it for posterity and to educate the American public about their national heritage. From 1927 to 1944 he created a historically based theme park at Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, that housed his vast collection, which included entire buildings such as Noah Webster’s house and the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop. Ford’s enthusiasm was highly motivated by an underlying patriotism. When he opened the Henry Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1933 he proudly stated: “We have no Egyptian mummies here, nor any relics of the battle of Waterloo nor do we have any curios from Pompeii, for everything we have is strictly American”. Similarly, in 1926 John D. Rockefeller began his obsession with restoring Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, which would eventually house his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s extensive collection of American folk art. Both Rockefeller’s and Ford’s efforts reflected the commonly held belief that the American past could provide an inspiration for its future. In a letter to Rockefeller, the editor of the American Collector framed his appeal to the philanthropist to create a center for American historical research as an imperative national necessity. He stated, “Our heritage from the heroic past must be preserved as continued guidance and inspiration to ourselves and to all mankind” (Kammen 1991: 322).

The economic crisis in the United States precipitated by the market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression seemed only to enhance this need to identify and draw support from American history and character. Paradoxically, at the same time, the need to push the country forward to progressive modern means also came to the forefront, causing a strange collision of both futurist and historical viewpoints. While modern innovations in American industrial design, architecture, and technology were showcased in the futuristic buildings and displays of the 1933 Century of Progress International Exhibition in Chicago as well as in the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, historical pageants celebrating American history and traditions were also being celebrated in the same venues. As Kammen explains:

The interwar decades were permeated by both modernism and nostalgia in a manner that may be best described as perversely symbiotic. That is each one flourished, in part, as a critical response to the other. Most of the time, however, there was a little if any recognition that an oxymoronic condition persisted: nostalgic modernism. (Kammen 1991: 300)

This so-called nostalgic modernism seemed particularly appropriate during a time when the threat to democracy by Americans’ interest in communism in the 1920s and ’30s, as well as the outbreak of war in Europe, created a sense of urgency to preserve the nation’s past and protect its future. The reality and visibility of this threat allowed notions of patriotism, the importance of tradition, and the preservation of national character come to the forefront as issues and concerns. The need to demarcate clearly American traditions as separate from their European predecessors was also evident. Many like James T. Flexner, a prominent historian and biographer of George Washington, recommended a clean break from European mores in order to find an appropriate national character:

In these days when European civilization is tearing itself apart much of the torch of culture is being handed to us, but we cannot carry it on adequately merely on the basis of the European tradition which has developed such cancers. We must explore our own past to find other, stronger, roots based on a continental federation, on a peaceful mingling of races, on a hardy and unsophisticated democracy that grew naturally from a hardy and rough environment. (Kammen 1991: 510)

This type of attitude led to a zealous kind of American “exceptionalism”—a unique brand of nostalgic modernism that reconciled modernity with tradition, technology with hand craft, and diversity with a sense of unity—that is evident in American culture in the late 1930s and war years. It occurs in the contemporary reinterpretation of American folk music in compositions of Aaron Copland, the abstracted contemporary American landscape paintings of Charles Sheeler, and the portraits of life in the South in the novels of William Faulkner. The idea that Americans would look to its past traditions for models for its modern future was not considered antithetical but essential. As social critic Lewis Mumford speculated: “Genuine tradition does not stifle but reinforces our interest in the present and makes it easier to assimilate what is fresh and original” (Mumford 1930: 525). Clearly Russel and Mary Wright’s own zealous Americanism shares Mumford’s sentiment and reflects the country’s general preoccupation with both celebrating and clarifying an American identity free from European influences. The pursuit of a particular American character for contemporary design is a consistent theme in all the Wrights’ work.

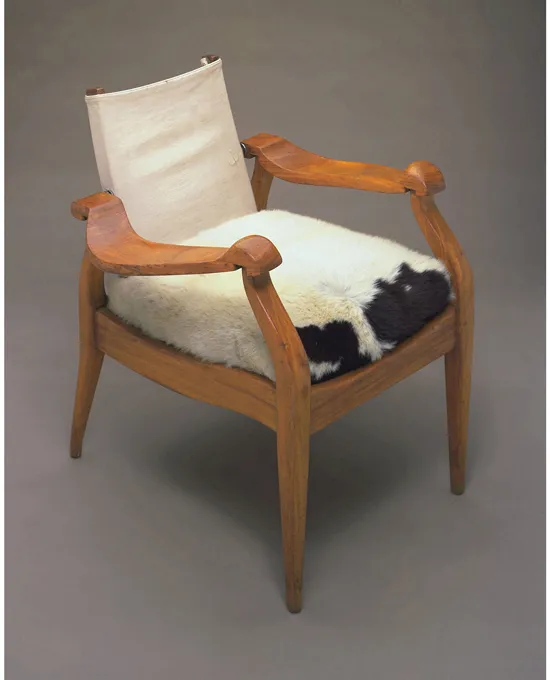

Wright’s first clearly nostalgic modern piece was his design for the Cowboy Modern chair of 1932 (Figure 1.1). This strange hybrid was an ergonomically responsive chair constructed of pony skin, painted vinyl, and carved wood. It looked like a crude cross between a Le Corbusier and Duncan Phyfe design, with solid blocky construction that attempted to visually reconcile the rustic craftsmanship of the American frontier with modern styling. Its pony skin, wood construction, and moniker also linked it with myths of the American West, the Great Outdoors, and the quintessentially American individualistic lifestyle of the cowboy that was being celebrated by the newly developing Hollywood movie industry in the 1930s. Its inclusion in Wright’s early interior spaces, such as his own apartment on East 40th Street in New York in 1937, adds warmth to the design’s cool geometric modernity and suggests a sense of history and tradition.

FIGURE 1.1 Russel Wright, Cowboy Modern chair, 1932. (Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum/Art Resource, Photo: Mike Radtke @Smithsonian Institution).

FIGURE 1.2 Russel Wright, Rendering of American Modern Furniture Line, c. 1935. (Russel Wright Papers, Syracuse University Libraries).

Like the Rockefellers and Henry Ford, the Wrights also turned to themes of the Colonial period for examples of authentic American character. In 1935, Russel Wright designed a line of solid wood furniture for the Conant Ball furniture company that was called American Modern (Figure 1.2). In the company’s promotional literature, it was described as a “twentieth century interpretation of the spirit behind American Colonial design—a spirit which prompted frank construction and honest simpl...