![]()

1

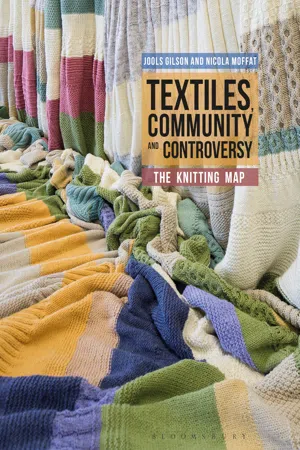

Navigation, nuance and half/angel’s Knitting Map

A series of navigational directions1

Jools Gilson

This writing is a navigation of failures. The safe channels in an estuary are marked by buoys; keep the red buoy to port and the green to starboard, and you will travel safely. But I am compelled by the spaces outside of the publicly marked, and I wonder if it is possible to make it to harbour by other routes. Such heretic navigation promises possibility, but failure lurks under the surface. Such danger is profoundly part of the aspirant pedagogy I describe here, in which failure is itself a kind of buoy, one which tempts an exuberant buoyancy, as much as it threatens being lost at sea. So that it makes the best sense to speak of a pedagogy of failure, rather than the failure of pedagogy.

This is a story about two publics; one involved in a vast collaborative knitting project, which used traditional as well as experimental gestures; the other a public who witnessed the same project through the media controversy that described it.

The Knitting Map was a departure for us as a company; we had spent ten years making dance theatre and installation work. In The Knitting Map we proposed a work that we hoped could be a gift to the city that was my home, and which was designated as European Capital of Culture in 2005. But by a contingent of its Irish audience (the majority of whom never visited the work), this gift was unwanted. So here is the affect of failure: It hurts. It is an injury. But being on the whole a cheerful and hardy traveller, and having made such an impossibly huge map, I’m off to chart this story with all its complexities of nationality, femininity, fury and love.a

Figure 1.1 Women knitting The Knitting Map in the crypt of St Luke’s Church, Cork, Ireland, 2005. half/angel.

We are called half/angel for a reason. The name is from a trapeze move, which I learnt when studying trapeze in the early 1990s. I loved it because one moment you are sitting prettily on the trapeze, with one hand grasping the bar, and the next you fall backwards holding on with that single grasped hand, and a flexed foot catches the place where wood and rope meet. If it works you fly underneath the bar, and you are half an angel. I long for such falling and such flight; movements in which you have to fall in order to fly. So we are half/angels, creatures equally enamoured of falls and flights, knowing in our bones and blood that there is a way to fall into flight.

But there are times when falling fails to turn into any kind of angel, even half of one. Learning this technique was a process of repeated indignity, training with a wide belt around our waist called a lunge. Should we fall, as we all do, our teacher pulls down hard on the lunge rope, so that we are caught, dangling in space. But we always try again, cajoled into ending with our (partial) angel intact. And in this way, failure is our guide. Being willing to fall is another.

And so we fall into the prosaic and everyday. We fall into our first tangle, in which some contingents of the press, and many of our knitters, believe our project The Knitting Map to be about a literal mapping of Cork City. We are appalled, whilst many of our knitters think of it as a lovely idea, and volunteer to knit particular parts of the city. Our understanding of processes of cartography assumed a poetic plurality. Our map wasn’t literal, because such literality would not have allowed us space to be playful with how cartographic energies depict all kinds of geographies, from the tone of laughter of the cartographer, to how Mary was late on that Tuesday, to the vast impossible secrets of the complexity of knitting, to the floods in March, and the snow in November, and the heat of August, and the lull in October, to Ciara’s poor tension, and Maura’s cable, and nobody cleaned the toilets on Sunday so I had to do it before I could change the wool for Monday, to the valuing of women’s lives and community, to the ferocity of some of the press, to people crossing oceans solely to visit us, to indignant men arriving surprised at quiet industry, to the way we laughed so hard we wet our knickers at Elizabeth’s leaving do, to the neighbours getting upset, to drums playing, and scones being eaten, to fury and love, and tears, and tension of all kinds, and love, and love. And women in Philadelphia weeping at the sight of it. How could we map that with something that was just a picture that imagined streets to stay in orderly parallels, and suburbs to remain peripheral, and all of that? And whilst we sat appalled, we began to understand that imagination is a privilege of unparalleled proportions, far beyond the material privations that play themselves out in the lives of too many of us. To be able to be playful with imaginative possibilities is to believe in different kinds of worlds. The vision of The Knitting Map – the women of a city rising up and knitting the weather for a year, has a revolutionary gesture at its core. Its poetic motion sought to find a quiet but profound way to give space to the astonishing in the everyday of so much feminine activity. It sought to give space to a profound politics of care, to ask if skills normally used for gift giving and solace, could be used for something of vast collaborative gorgeousness, something whose use-value (a thing that would so often trouble our critics and collaborators alike) was both poetic and political.

A small boat under oars need show only a lantern or electric torch in sufficient time to prevent collision.

RYA International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (Anderson 1995: 18c)

Reverse Stocking Stitch Check in Nutmeg.

Quiet. Sister Susan and the girls from Knocknaheeny.

The Knitting Map Log (2005: 7 June)

Holding on to my trapeze with a clasped hand and readying my flexed foot, I drop backwards. And my repeated tangling with rope and wood is still happening when I sit down and knit in this cacophony of knitting that is The Knitting Map. Here I am falling, and whilst failure attends my learning and my teaching, I am brave enough to carry on catching wool and knitting needles like a trapeze move, but this time, it is the hundreds of women who visit daily who perform stunts between their dextrous arms and fingers, and the twine of wool. And they come with us to risk flight.

Risking flightb

In half/angel’s project The Knitting Map, digital codes were written to translate information about how busy Cork City was, into knitting stitches, and what the weather was like, into wool colour. This information was uploaded to digital screens as a simple knitting pattern (knit this stitch in this colour), and volunteer knitters sat at twenty knitting stations in a wooden amphitheatre in the crypt of St. Luke’s Church and knitted. And they did this every day for a year. (Barkun, Gilson-Ellis & Povall 2007: 13–14)

The technology that was part of imagining The Knitting Map had been part of half/angel’s performance and installation practice for ten years prior to 2005. This work with technology allowed us to haunt performance and installation with unsettling connections between gestures and voiced text or music. In The Lios (2004), gallery visitors moved their hands in pools of water to trigger recordings of a community remembering the sea, as if memory itself were dissolved in water. In The Secret Project (1999), dancers moved and spoke poetic texts whilst producing another layer of the same text with their movement, so that they and the audience became unsettled by a vocal and corporeal plurality, and time itself seemed troubled. If we had not spent a decade refining this kind of work we could not have imagined The Knitting Map, in which a city and its weather generated knitting stitches and wool colour.

Figure 1.2 Edge shot of The Knitting Map, from an exhibition at Millennium Hall, Cork, Ireland 2006. half/angel.

The Knitting Map, then, involved the culturally disenfranchised in the making of a vast artwork that was commissioned (and certainly perceived) as a flagship project for Cork’s year as European Capital of Culture in 2005. Poetically and politically it was a work that sought to rework the urban territory of matter and meaning: knitting was used as something monumental – an abstract cartography of Cork generated by the city itself and its weather, and knitted every day for a year. To make such a gesture using feminine and female labour aspired to rework the relationship between femininity and power in an Irish context – it gave cartographic authority to working-class older women from Cork, for a year.

The process of conjuring the energies of a city’s climate into an abstract cartography meant that in an important sense the women involved in making The Knitting Map were knitting the weather. Such a communal gesture brought frosts and floods, and heat into the domestic and ordinary act of knitting. It opened its close, domestic and feminine associations to the literal and metaphorical sky. The Knitting Map also allowed the mathematical complexity of knitting difficult stitches to be brought into proximity to a frantic city, clogged with traffic and queues, and crowded streets. In keeping track of shifting numerical combinations to produce, for example, an open honeycomb cable,2 these women reworked the actual digital information about busyness being sent up to them from the city, and they did so by integrating this data with their hands (their digits) in processes of communal hand-knitting. The Knitting Map allowed the prevailing cultural peripherality of middle-aged women to make a collectively original and beautiful thing, and in doing so remapped their own apparently tangential geography.3

Tidal streams flow towards a direction.

Winds flow from a direction.

Navigation: An RYA Manual (Culiffe 1992: 102)

Tw2RW: Slip next stitch onto cable needle and leave at back of work, knit one, then purl one through back of loop from cable needle.

Debbie Bliss, How to Knit (1999: 158)

Yacht masterc

I am a Yacht Master, but I cannot sail. I have a certificate from the Royal Yachting Association with my name on it. I have only once been in a yacht, and when we were out at sea, dolphins suddenly surrounded us – they were underneath us, and leaping beside us. They wove such playful curves again and again, that I was undone with the joy of it, stumbling from one side of the small boat to the other to look at them. The old man I sailed with had sailed all his life, and had never seen such a performance. In class I had become enchanted with extraordinary maps of the sea called charts, and a new language: ‘chart datum’, ‘dead reckoning’, ‘isolated danger mark’. We learned about meteorology, navigation and collision regulations. I took notes and drew coloured diagrams. And when it came to the exam, I got the best mark in the class. But as I sa...