![]()

PART ONE

Environment-worlds

![]()

1

Environments

On Tuesday much of Christchurch abruptly collapsed to the ground. The Cathedral lost its steeple. Closer to home, and all that summer, the eastern seaboard had been inundated with water. Dislodged interior furnishings were adrift down erstwhile suburban streets. Wild winds assailed coastal towns and from time to time the smaller settlements in the hills were razed by fire. Some ten years ago now the family home succumbed to wayward flames. She walks its ghostly perimeter attempting to revivify the architectural corpse. Where there was once floor, now there is ceiling and remnants of rafter. Where the roof once proudly kept at bay the forces of inclement weather, there is now only thin air. It is a radical redistribution of materials.

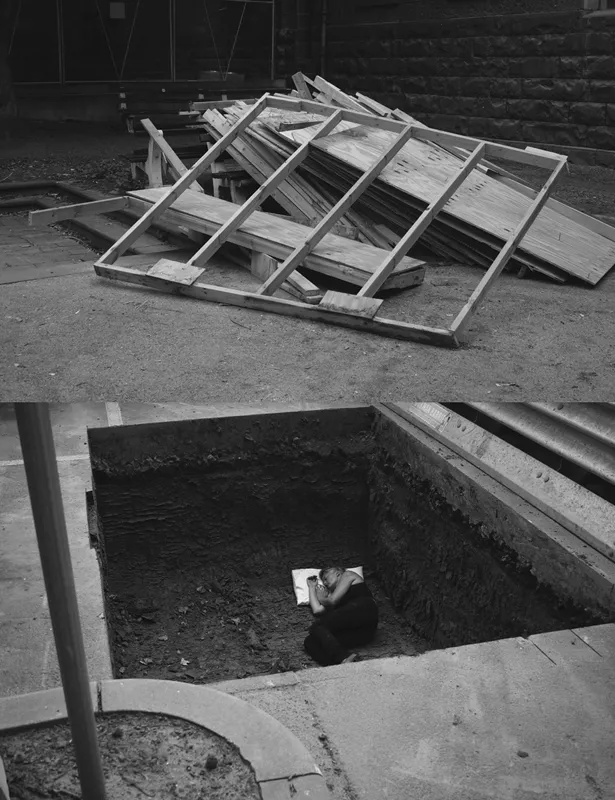

ADRIEN ALLEN, Hélène Frichot and Bridie Lunney (2011)

In this first chapter, I proceed from a reflection on environments and ‘environmentalities’ towards worlds and ‘worldings’ in order to arrive at the conceptual construction of environment-worlds. Environment and world are placed in disjunctive relation to create the compound environment-worlds, a literal translation of the German word Umwelten. From there, I circle back around in Chapter 2 to a discussion of ecologies in order to introduce what the philosopher of science Stengers calls an ecology of practices. As well as alluding to the organization of the household, ecology, oikos and logos, tells us of the intimate connection between organism and environment. More specifically for my purposes, it is a term that sends me towards the promise of ecologies of creative practice, that is to say, the practices that take place amidst environment-worlds, and what we do there as we make the places where we live and die more or less habitable. And so, in Part One, I explore an incremental additive process, overlaying one term upon the other in order to suggest a conceptual construction that sets the scene for ecologies of creative practice. It is a survey that no doubt attempts to travel too far and wide for the conceptual territory I apprehend is growing daily. I conclude with an introduction to exhaustion, understood not only as an affective demeanour, both conceptual and corporeal, but as a methodology and even a means of further creation. Exhaustion will be considered distinct though related to the extinction events we experience today as human and non-human creatures across post-human landscapes. Exhaustion, I venture, can be reconstructed as a methodology of exhaustion. It is an approach that I have learnt slowly, incrementally, iteratively, through my encounters with critically aware architects, designers and artists, whom I am calling creative practitioners. I hasten to add that this is not to exclude other kinds of practitioners from creative work, but only to allow me some specific disciplinary focus. The methodology of exhaustion, as I will progressively demonstrate, follows one slow step at a time so that connections between things and thinkables and environment-worlds can be rendered durable, even if only provisionally.

Figure 1.1Bridie Lunney, Suspension Test. Research image, 2011.

Environments

If you were to ask me I would struggle to tell you anything about my environment. Do I start, as do too many philosophers, with my desk? Do I extend outwards by way of concentric rings from a domestic or an institutional environment, depending on what day of the week it is and where I happen to be sitting? Should I speak of the woods that are accessible at the edge of town? Is that where the environment is to be found? Should I address the virtual environments I am plugged into on a daily basis, surfing, uploading, downloading, updating? This is what has provoked the question of environments, the recognition that I am unable to offer an adequate answer. Environments are ubiquitous, everywhere, yet I feel ill-equipped to speak of them and how they are composed. I remain wary of attempts to offer exhaustive historiographies of the concept cum material conundrum that is ‘the environment’; though I admire such efforts, they inevitably leave out too many minor voices (Sörlin and Warde 2009; Warde, Robin and Sörlin 2018). From this position I am obliged to hesitate, to express my limits, which means I am also prepared to bear witness to what I encounter. What do environments do? I know in a general sort of way that environments surround all living things, offering them support and sustenance. I understand that without environments there is no life for the living creature, and that at the same time the living creature reciprocally ‘environs’ its local scenes through modes of action particular to its capacities. Organism and environment operate in a contrapuntal relationship, which is not to say that the power relation between them is always balanced.

When it comes to architecture, the first environment we tend to acknowledge is the built one, where environments operate as designed technological infrastructures, facilitating the presumed exceptionalism of human life and too often forgetting the profound intermingling of diverse forms of life. Architecture contributes to the manufacturing of environments across varying scales, and is in turn nested within environments, real and virtual. Our vulnerability and fragility become pronounced, as Judith Butler writes, when these designed infrastructures fail us (2014, 2015).

Environment is a word that, despite the pervasiveness of its material effects, too often recedes into the background of architectural and creative practice considerations. Environment is inescapable, despite the human creature’s desire to propel itself beyond the atmosphere to secure another point of view on what it presumes to be its world, a world imagined as a blue-green Christmas bauble hanging in space (Kepes 1972: 10). It is tempting to believe that the word ‘environment’ names some place that is out there; and in some vague and diffuse way, we (humans) know that an environment supports us, but we rarely think of how we depend on it for our survival and for the very forms of life we express. We know that an environment supports us, but somehow to think about it renders it fragile and unstable. Neither can this ‘we’ that I have just now incanted be considered as without presumption, for the ‘we’, whoever we are, is equally at stake in rethinking architectural environment-worlds, where the complex question of what environments do is compounded with the means by which worlds are constructed.

Who are we who gather around our matters of care and concern amidst an environment-world? Many implicit assumptions are sheltered in the simple enunciation of a ‘we’. Are you with me or against me? Who is this ‘we’ you claim to speak for? (Stengers 2012; Tsing et al. 2017: M4–M5). Gregory Bateson states it simply as: ‘in the pronoun “we” I of course included starfish and the redwood forest, the segmenting egg, and the Senate of the United States’ (Bateson 2002: 4) – which is to say, as Eduardo Kohn points out in How Forests Think: ‘“We” are not the only kind of we’ (2013: 16; emphasis in original). A diverse mix of different kinds of assembly that collect not just humans and non-human creatures and life processes, but institutional arrangements and technological infrastructures, and which demand that ‘we’ likewise reorient our thinking about, and practising amidst, environments. A ‘we’ immediately suggests an assembly of socially conscious participants sharing some matter of concern or care. ‘Who speaks and acts? It is always a multiplicity, even within the person who speaks and acts. All of us are groupuscules’ (Foucault and Deleuze 1977: 206), including the fact that the greater part of our bodies is composed of ‘bacteria, fungi, protists, and such’ (Haraway 2007: 3; Tsing et al. 2017: M3–M5), as Haraway is fond of pointing out. This means that rather than the habitual emphasis on the sovereign human subject, we are obliged to think in terms of our species-being as humans (Barber 2016: 1167; Chakrabarty 2009) and the effects we have made at a macro-scale, and how these effects hit the ground amidst the ordinary affects and circumstances of everyday life.

Who is the Anthropos anyway? This is a question raised when environmental and ecological issues are discussed today in light of the Anthropocene thesis (Alaimo 2017: 89–120; Colebrook 2017: 10; Heise 2017: 5; LeMenager 2017; Stengers 2013: 176) and when addressing an exhausted earth. While the Anthropos, designating the human species-being en masse, is a more circumscribed part of the lively and diverse ‘we’ described earlier, the act of rendering it exceptional or privileged, beyond culpability, is an act likely to conclude in the diminution of its own collective well-being. Who do we think we are anyway? Should all human life and expression be collapsed under the category Anthropos if it is a more circumscribed set of human actors that have collectively brought about the earth’s geological transformation? Nevertheless, ‘we’, in being earthbound, all seem to be in it together. Who is the Anthropos? is not a question with an adequate answer, and no doubt needs to be shifted to something like: What do we think we are doing? For the creative practitioner at least, this becomes a speculative issue of adequate ethico-aesthetic practices explored amidst situated, singular and collective experiences and experiments. Ethico-aesthetic practices pertain to ecologies of creative practice, bringing together modes of (aesthetic) expression with an awareness of the ethical implications of such expressions.

Environment is what unfurls when the architect or creative practitioner turns her back to the built object – which is an environment of a special sort, contained, ‘well-tempered’ (Banham 1984) and controlled – and witnesses another point of view; yet it is not a vista that can be claimed as though the architect or creative practitioner safely stands outside a situation to look out across a landscape. Position is always embedded in facilitative environments, which are the milieux that render creative projects possible. This is what Maria Reiche demonstrates from the top of her aluminium ladder, securing a technologically augmented position just above the ground, all the while embedded on the earth and deeply involved in her material practice.

Environment, when taken for granted as a given and stable condition, is that which is mapped and analysed as a site prepared to support future construction and world-making projects, but the environment is never simply a given condition; it is far more lively than that and likely to surprise. The environment is neither stable nor passive. It is not simply a natural resource to be plundered, nor simply a cultural condition to be further organized via acts of rarefication and construction. Science studies thinkers such as Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour have taken to conjoining these modifiers, natural and cultural, in order to insist on a conceptual construction: Latour’s nature-culture (Latour 1993) or Haraway’s naturecultures (Haraway 2007; 2016). We should be wary of the ‘Nature/Culture schema’ (Latour 2017: 226) where the backslash insists on absolute division, or what Latour describes as modernist purification. Andreas Malm offers warnings here, suggesting that this conceptual sleight of hand, this hybrid amalgam of society and nature (he speaks of society rather than culture), risks dissolving the two terms, rendering them indistinguishable, even eradicating them altogether (2018: 83–88). I believe something rather more complex is at work. I argue that these loaded terms maintain their distinction, and at the same time they cannot be easily disentangled. They do not collapse, but clinch together. The challenge, it would seem, is to maintain this clinch, nature-culture, in a quivering embrace, to not entirely collapse the distinction between the terms, but neither to draw them dangerously apart. It is neither a ratio that can be stabilized nor a relation that can be equalized once and for all. It is not a container in which things simply sit, but contributes to the very formation and life of things by way of a relational ontology, which is what Actor Network Theory (ANT) and Science Technology Studies (STS) teach us. And this would appear to be where environments, with an emphasis on the plural, are laid out, in this tangle, like a complex conceptual knot or a scrubby patch of weeds.

Embedded in a rhythm of embrace and withdrawal, the creative practitioner is swallowed by, and then emerges out of the background of, her environmental milieu, advancing and receding, creating as she goes so many intersecting ripples, unexpected connections, patterns of diffraction and entanglements.1 There are foregrounds and backgrounds, depending on position and point of view, but there is no offstage to the world. When the creative practitioner goes to work, she transforms her environment-world, at the same time as transforming herself, at the same time as being transformed by her environment-world – even if, as Rachel Carson once suggested, the environment endures far longer than the human creature (Carson 2002); even if, as Stengers states, the world will continue without us and we will constitute yet ‘one more “contingent event” in a long series’ (Stengers 2000: 144; also cited in Colebrook 2014a: 29); even if, as Gilles Deleuze has remarked when he reads Michel Foucault, ‘we must take quite literally the idea that man is a face drawn in the sand between two tides: he is a composition appearing only between two others, a classical past that never knew him and a future that will no longer know him’ (Deleuze 1988a: 89). The man-form is ‘destroyed by that inexhaustible force’ (Foucault 1970: 278) as oth...