![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Trajectory of India’s Urban Development

Colonialism shaped the economies, roles and distribution of cities in India. Before 1800, India already had a well-developed urban system. During the period of colonialism, cities were occupied and developed to serve the economic and political interests of the colonisers. The colonial enterprise of the British mainly focused on the primary production of a few specialised commodity lines for export. For example, investments were made in mines, plantations and tea gardens, and for movement of their produce to the port cities. In turn, facilities for payments were created to ensure flow of money from port cities to local areas. This is termed as vertical trade in a market system.

In contrast, the British ignored horizontal trade, which largely developed as a by-product of vertical trade. As a result, horizontal trade was limited to buying of provisions in the rural markets for the urban middle class and selling to some industrial or other city goods to them. The extreme focus on the export of a few commodities led to a dynamic vertical trade and a static horizontal trade, which led to a spatial form that consisted of the three following types of settlements:

• Major port cities with strong links to Britain: The port cities served the surrounding territories in the collection of commodities, largely raw materials, for export, and the distribution of other commodities from overseas as imports; the latter primarily consisted of manufactured items. Gradually, the port settlements evolved into market centres and producers of low-value manufactured goods due to the economic activity generated by their constant link with the external metropole (London).

• Strategic cities connecting the port cities to local areas in the interior hinterlands: Linear forms of transport links were built in order to connect port cities to the strategic cities for bulk exports, consolidating the purchase of primary products, and breaking wholesale lots of consumer goods for distribution to smaller markets.

• Dispersed local market places, which were dependent on strategic cities for transport, processing, storage, bulkbreaking and credit facilities: In this case, artisanal products and agricultural commodities were not exported, but exchanged locally. The British engaged in some ancillary activities, such as the establishment of transport and communication facilities, maintenance of law and order and, later on, the creation of regulated markets for agricultural products.

The spatial system consisting of a few towns and abrupt gradations in the hierarchy of settlements was skewed. For example, Johnson3 found that in the area surrounding the city of Kanpur, there were 11, 239 villages and only twenty-four towns and cities. This gives an average of 468 villages for every town. Had the inter-urban hierarchy not been skewed, the ratio would have been the same as in the United States, which means India would have had 47,000 towns instead of having less than 2,000.

At the time of Indian independence in 1947, the urban hierarchy exhibited the following characteristics: (1) a few large cities, mainly located on the sea-coast, (2) some interior cities closely connected to port cities and strategically located along rivers, railway junctions and roads for extraction of resources and distribution of imported manufactured products in the countryside, (3) large number of villages, (4) and lack of integration among cities and between cities and villages due to under-developed horizontal trade.

Post-independence Urban System

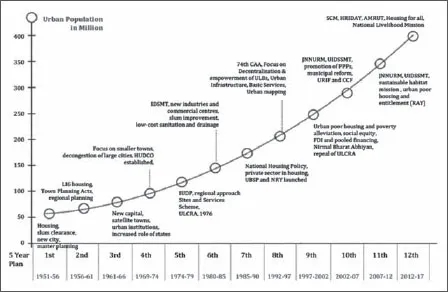

Post-independence, urban development was subsumed under India’s Five Year Plans (FYPs) and Figure 1 gives the focus of the successive FYPs. Based on the attention that the government paid to the urban sector, the trajectory of urban development in Indian cities can be broadly divided into three stages. The first stage spanned fifteen years (First to Third Five Year Plans) and urbanisation happened by default. The first three Plans were marked by efforts towards housing provisions, slum clearance and rehabilitation. The Second FYP provided for the formulation of town and country planning laws, establishment of planning institutions and preparation of rigid Master Plans. Two state capitals and industrial towns were developed during the Third FYP.

In the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth FYPs, urban planning took a different pathway – the Fourth FYP emphasised the need to limit the growth of urban population; the Fifth FYP promoted smaller towns; and the Sixth FYP focused on towns, and the development of roads, pavements, bus stands, markets, etc. Overall, slum clearance gave way to slum improvement, while the emphasis shifted to the development of small and medium towns and the promotion of balanced regional development.

Figure 1. Plan period-wise policy focus

Source: C-Step (2015)4

During the 1990s, the urban sector was accorded greater attention, heralding the start of the second phase. The Constitution was amended by way of the 74th Constitutional Amendment and this enabled the devolution of funds, function and functionaries to the urban local bodies. Interest in the development of cities was renewed with the launch of the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM) in 2005 across sixty-five large cities. This was later expanded to cover smaller cities as well. Planning in JnNURM led to the emergence of City Development Plans (CDPs) with a focus on project-based infrastructure development. Master Plans continued to be the bedrock of spatial planning with a set of Development Control Regulations (DCR) being enforced locally.

A key gap in the first two phases was the lack of integrated planning and inordinate focus on infrastructure creation, instead of the delivery of services to citizens. The third phase though marks a clear departure from the past and is based on the idea that cities are complex eco-systems where different systems (for instance, transport, sanitation) influence one another and evolve in the process. The planning of Smart Cities captures these inter-connections and interactions among systems, and the integration of these is carried forward to the implementation of Smart Cities as well. In this way, urban missions in the third phase mark a shift towards a ‘system of systems’ approach than can lead to the holistic development of cities.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Idea of an Indian Smart City

A key characteristic of the unique Indian culture is its self-organising behaviour. The self-organising system generates informal rules of practice. The informal rules of practice are a form of ‘calculated informality’, which ‘involves purposive action and planning… where the seeming withdrawal of regulatory power creates a logic of resource allocation, accumulation and authority… in this sense that informality, while a system of deregulation, can be thought of as a mode of regulation. And this is something quite distinct from the failure of planning (decision-making) or the absence of the state’.5 This informal mode of regulation operates at multiple levels—national, state, district, city, locality and household.

Useful insights into the modes of regulation can be found in the work of Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom. In her study of the mechanisms of self-governance operating in the less-developed world, Ostrom found that decentralised groups develop various rule systems that enable social co-operation to emerge through voluntary association. She found that non-State decision-making follows ‘rules in use’ and accomplishes what the State mandated ‘rules in form’ would have been expected to accomplish. A casual observer would often label the results of the interaction of ‘rules in form’ and ‘rules in use’ as chaotic. However, there is an order in this apparent chaos and the idea of order out of chaos 6 is at the core of the theory of complexity.

‘Rules in use’ arise as a result of the interaction between two types of entities—material and human operating in cities7. On their own, the material entities such as buildings, roads and bridges are simple systems and do not interact with one another to produce complexity. It is in the presence of human beings that interactions take place, and which in turn generate complexity due to the interaction of people with material entities and the environment. Moreover, urban agents have the ability to think, learn and decide, which means that they are natural planners and designers. Thus, the ‘rules in use’ arise as a result of these spontaneous bottom-up processes. Therefore, as Jane Jacobs8 suggested, urban planning has to move towards a science of ‘organized complexity’9.

From this perspective, cities are not machines, but complex systems. Cities conceived as complex systems have certain characteristics discussed as follows. Firstly, bottom-up ‘rules in use’ are generated due to the interaction of residents with one another, between artifacts of the city (such as roads, bridge, localities), and the natural environment in the Indian self-organising culture. Secondly, the ‘rules in use’ are difficult to identify or explicate because the connection between the ‘what’ and ‘how’ is not linear. Therefore, the connection cannot be predicted using a technical-rational process. Thirdly, interaction among residents, city artifacts and the environment leads to feedback loops. A feedback loop is an action that affects other parts over the course of time, while the consequences of this action come back to affect the original part that caused the disturbance. Finally, these three features of complex systems (open, non-linear and feedbacks) lead to unexpected outcomes and behaviours in the city-system.

In the presence of bottom up self-organising systems, a top-down, one-size-fits-all policy (used interchangeably with mission) is unlikely to work10. A cookie cutter policy may be implemented as stated, or not be used as stated, or go by one name, but on the ground it will have an entirely different effect. The overall effect is that policies remain formal in appearance, but play out differently during implementation. This leads to the well-known gap between policy and execution. What is required is that the policy should capture the interaction among residents, and with their material entities and environment. In other words, the policy should aim to minimise the mismatch between the ‘rules in form’ created at the top and the ‘rules in use’ emerging at the bottom. One way to minimise the mismatch is to design a policy in which considerable scope is given for local ‘rules in use’ to play out, thereby, resulting in a closer fit between ‘rules in form’ and ‘rules in use’. A policy which is in the form of a broad framework and gives considerable scope to the local administration to operate, enables contextual rules in use to be incorporated during planning and implementation. Such a policy is called ‘loose fit, light touch’. The Smart Cities Mission guidelines were in the form of a broad framework wherein the cities could plan and implement their projects keeping the local conditions in mind.

![]()

CHAPTER 3

The ‘Loose Fit, Light Touch’ Framework

Typically, government schemes prescribe a cookie cutter model with little or no room for adaption to local conditions. This one-...