eBook - ePub

Quality Management

Tools, Methods and Standards

- 325 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The current economic climate, characterized by growing international competition, is forcing companies to rethink their approach in terms of strategy, the customer and supplier relationship, processes and human resource management. In this context, 'quality management' - synonymous with efficiency, effectiveness and competitiveness, becomes essential.

Quality Management: Tools, Methods and Standards fills a gap in the current literature by providing an updated overview of the discipline and its boundless fields of application from industry to public administration. Written by authors with both academic and practitioners backgrounds, the book serves as a culmination of the knowledge they have gained as managing directors and chairmen of leading companies. Starting from the history of quality, the authors provide the reader with a review of the main tools and approaches aimed at improving effectiveness and efficiency in organizations. Balanced scorecard, QFD, and FMEA are some of the solutions that are first introduced theoretically and then described in their application. International standards are also broadly discussed: ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 45001, ISO 27001 and SA8000 are described in their essential features and implementation patterns.

This book should be considered a must-read for students, academics, and practitioners who are interested in the theory and practice of quality management.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

History of Quality

1.1. What is Quality all About?

We have posed the same question many times entering a new class on quality management. How can quality be defined? The answers – be it from undergrads, master students, or executives – tend to converge on a production-oriented kind of understanding, “conformity” and “specification” the words coming up more frequently. Every now and then, someone would try out a different answer, bringing up ideas such as “product performance,” “customer satisfaction,” or even the “way you do your daily activities.”

Conventional wisdom collocates quality in the field of operations management and related engineering disciplines. Reality is that there is no single truth behind the concept. Most certainly, many methods and techniques have been developed in connection with the challenge of manufacturing products without defects. It is also true, however, that quality is an overarching concept which has applications both in the business environment and in everyday life.

The term “quality” is commonly used to mean a degree of excellence in a given product or activity. Most of the people would agree with that. Philosophers have argued that a more precise definition of quality is not possible: building on discussions initiated by Socrates, Aristotle, Plato, and other thinkers in Ancient Greece, quality is understood as a universal value that we learn to recognize only through the experience of being exposed to a succession of objects characterized by it (Buchanen, 1948; Piersing, 1974).

In a business setting, such a general understanding is, however, not sufficient. Where does quality end and non-quality begin? Are there different degrees of quality? If so, is it possible to measure quality? These are only some of the questions that have been raised in academia and in industry, and the answers have been very different (Reeves & Bednar, 1994).

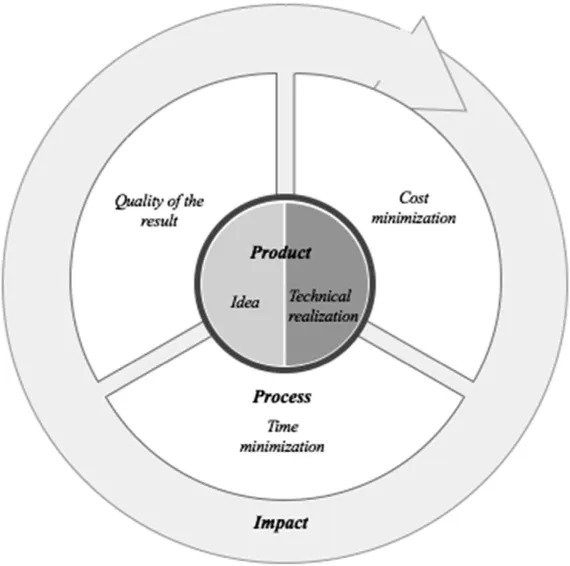

To begin with, quality might refer both to a product (or service) or to the process that generates it. In terms of product quality, there are multiple possible dimensions or elements (Garvin, 1984). Some of these elements refer to the quality of the technical realization of the product and are usually objective and measurable, such as conformance. Other elements are instead less objective, as the preferences of the customers might vary in relation to them: they can be measurable, such as product performance or durability, or purely qualitative, as in the case of aesthetics. This last set of elements might be understood as the degree by which the product (or its initial prototype) is fit to customer expectations or the quality of the idea. A similar line of reasoning is also applicable to services.

In operations management, the most attention has historically been placed on the quality of technical realization, described as conformance of a product to a design or specification (Crosby, 1979; Gilmore, 1974), and the cost of attaining it with respect to the price the customer is willing to pay (Feigenbaum & Vallin, 1961). Vice versa, economists and marketers understanding has mainly been focused on the quality of the idea, seen as a precondition to customer satisfaction. In this respect, the main questions have been revolving around the characteristics or attributes a product should have (Abbot, 1955; Leffler, 1982), and their appraisal considering different individual tastes or preferences (Kuehn & Day, 1962; Maynes, 1976; Brown & Dacin, 1997).

Several efforts have been made over the years to combine these two perspectives into all-encompassing conceptualizations and practical approaches. However, even nowadays, it is not unusual to see companies where this dialectic evolves into acrimonious meetings: designers, marketing, and sales executives on one side, production managers on the other. In fact, the relevance of the quality of the idea and the quality of technical realization (and the understanding of their underlying elements) varies significantly within each company, depending on the responsibilities and goals of each function (e.g., product development, production, and sales), stage in the product life-cycle, and, if present, positioning of the different product lines. The definition of quality varies significantly also across companies, even in the same industry, based on their value proposition. There are many examples of this. In the piano industry, for instance, Stainway & Sons has built its reputation as quality leader based on the uniqueness of the sound and style of each handcrafted product. On the other hand, Yamaha has also developed a strong reputation for quality emphasizing totally different dimensions more related to reliability and conformance (Garvin, 1984).

The definition of quality shall, however, not be limited to the final product. Again, different dimensions in terms of process quality have been investigated over the years. On the one hand, the question has been how to ensure the final quality of the result (Reeves & Bednar, 1994). On the other hand, a more comprehensive view has suggested that quality is related not only of processes efficacy (i.e., producing quality products), but also to their effectiveness (i.e., cost and time minimization). Process quality has been investigated by several disciplines, including but not limited to operations management (e.g., Anderson et al., 1995; Flynn et al., 1994; Saraph et al., 1989) and organizational behavior (Ivancevich, Matteson, & Konopaske, 1990).

Finally, in recent years, quality has also been related to sustainability and the effects (or, in economic jargon, externalities) of a company’s decisions and activities on a broad set of stakeholders, including the society, the environment, and future generations. This dimension is referred to here as quality of impact.

Overall, quality is a multi-faceted concept, whose definition is complex and fundamentally context-dependent (Reeves & Bednar, 1994). Fig. 1 illustrates how the different meanings of quality explained above unfold into concentric circles. At the center, product quality in its two dimensions: quality of the idea (prototype or design) and quality of the technical realization (conformance). Around it, process quality, in terms of effectiveness (quality of the result) and efficiency (time/cost minimization), which should be considered both at firm and supply-chain level. Finally, the outer circle embraces all previous dimensions of quality and represents the company’s and its products’ impact.

Today, we tend to have a comprehensive understanding of quality. Even though functional (in companies) and disciplinary (in academia) differences in terms of focus and priorities remain, we are aware that a one-dimensional view on the topic is not sufficient. As this historical review will show, however, this has not been the case for most of the modern history.

Fig. 1: The Different Meanings of Quality.

1.2. Approaching Quality in History

The history of quality extends for millennia, spanning over different geographies and socio-political systems. Throughout the evolution of civilization, many of the methods and tools that constitute the foundations of the current approach to quality have been developed, such as quality warranties, standardization, interchangeability, inspections, and laws for consumer protection. Already in ancient times, trained craftsmen not only provided clothing and tools, including equipment for armed forces, but also built roads, bridges, temples, and other masterpieces of design and construction, some of which endure to this day. Managing for quality is by no means a product of the modern Western world (Juran, 1995).

Industrialization was, however, a real game-changer as, differently than in the past, a more fragmented division of labor and the use of machines made virtually impossible to account the responsibility for the quality of a product to a specific individual (Weckenmann, Akkasoglu, & Wener, 2015). New solutions needed to be found, and this is where, experts believe, quality management as a discipline was born. This historical review also starts from here.

Since then, many progresses have been made, and quality management practices become mainstream. Many prominent thinkers have punctuated this evolution; however, a review of their publications would not give a realistic view of how quality has been developing over the years. It is not about “inventions.” It is rather about how and when these inventions have been adopted consistently with the challenges faced by companies, policy-makers, and individuals at any given time. On this basis, in the following paragraphs the history of quality is presented taking into account the changing context of international competition, customer expectations and technical opportunities. Since the various approaches to quality have been implemented in a different timeframe according to country- or industry-specific situations, the five phases described below do not present a linear evolution, but rather a chronological progression in which contrasting approaches, often in response to different challenges, might have occurred at the same time.

1.3. Quality at Time of the Industrial Revolution(s): Quality Inspection

In the age of craft production, there was a comprehensive understanding of the meaning of quality. Artisans, and merchants for their part, had strong ties to their local communities and often a personal knowledge of their customers. Laws would enforce the fulfillment of basic demands concerning society, whereas at least since the Middle Age, guilds promoted standards to ensure product quality punishing any deviation considered as fraud. Honor and personal accountability would complement the typical approach of craftsmen to quality. As the precondition for economic trade to be profitable is to meet customers’ expectations and do it effectively in terms of time and cost, they also acknowledged that quality needed to be pursued at all levels, from product design to realization and delivery. Both aspects of product quality (the idea and its technical realization) were important, even though the latter was not strictly understood as conformance: details would make a product unique.

This picture changed dramatically with the advent of mechanization. First, between the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, steam power and the development of machine tools impacted a first cluster of industries, mostly raw materials and semi-finished products, including textiles and iron making. One century later, in what is commonly known as Second Industrial Revolution or Mass Production, electrification was introduced to a broader range of industries. New technological opportunities gave rise to a series of managerial innovations, first and foremost, the implementation of the moving assembly line by Henry Ford in 1913 and the conceptualization of scientific management by Frederick W. Taylor (1911).

On the demand side, a new class of industrial workers was born. After the many drawbacks in terms of working conditions and living standards brought about by the First Industrial Revolution, the paradigm changed significantly after the 1910s as workers were now ensured decent-enough wages to make them become potential customers (De Grazia, 2005). In order to serve this increasing customer base better than the competition, companies needed to provide goods fast, in volume, and at a low price.

In this scenario, the meaning of quality was entirely related to the product technical realization, now decoupled from the quality of the idea. As an effort to reduce costs, and thus the price to the customer, companies pursued a low product variety: customer needs were hardly considered and product properties were defined by the will of the organizations (Weckenmann et al., 2015). The words of Henry Ford are famous in this respect: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.”

The game was thus all played in production and related operations. Here, while the division of labor was not a new concept, mechanization and especially the moving assembly line had led to an increasing specialization of the workers, now focused on single repetitive tasks. Workers in such settings failed to see the contribution of their activities to the quality of the final product, and it was no longer possible for managers to trace individual accountability.

In order to ensure the quality of products and avoid complaints from customers, companies started performing activities of quality inspection (QI). Again, QI is not a new concept, being part of every kind of organized production from Ancient China’s handicraft industry and mediaeval guilds to quality acceptance inspections of raw materials and semi-finished products at the time of the First Industrial Revolution (Nassimbeni, Sartor, & Orzes, 2014). However, as production volumes were growing to unprecedented levels, traditional QI was not up to speed with increasing labor productivity. Often defective products were delivered to customers and replaced with new ones only after complaints. A new systematic approach to QI was needed in order to reduce cost and complexity. Many companies established thus a separate inspection department: following Taylor’s (1911) recommendations, designated employees would check the quality of the products at the end of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1. History of Quality

- 2. Stakeholder Management

- 3. Statistical Tools for Quality Management

- 4. The Balanced Scorecard

- 5. Quality Function Deployment (QFD)

- 6. Benchmarking

- 7. Customer Satisfaction Analyses

- 8. Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA)

- 9. Lean Management

- 10. Six Sigma

- 11. Process Mapping and Indicators

- 12. ISO 9000 Quality Standards

- 13. ISO 14001

- 14. ISO 45001

- 15. ISO/IEC 27001

- 16. SA 8000

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Quality Management by Marco Sartor, Guido Orzes, Marco Sartor,Guido Orzes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.