eBook - ePub

Life Imprisonment and Human Rights

- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Life Imprisonment and Human Rights

About this book

In many jurisdictions today, life imprisonment is the most severe penalty that can be imposed. Despite this, it is a relatively under-researched form of punishment and no meaningful attempt has been made to understand its full human rights implications. This important collection fills that gap by addressing these two key questions: what is life imprisonment and what human rights are relevant to it? These questions are explored from the perspective of a range of jurisdictions, in essays that draw on both empirical and doctrinal research. Under the editorship of two leading scholars in the field, this innovative and important work will be a landmark publication in the field of penal studies and human rights.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life Imprisonment and Human Rights by Dirk van Zyl Smit, Catherine Appleton, Dirk van Zyl Smit,Catherine Appleton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Challenge of ‘Life’ in the Americas

1

The Impact of Life Imprisonment on Criminal Justice Reform in the United States

I.INTRODUCTION

AS OF 2015 President Barack Obama had issued sentence commutations to 184 individuals held in US federal prisons, nearly all of whom were convicted of drug charges, and one-third of whom were serving life sentences (US Department of Justice 2015). Among them was Clarence Aaron of Mobile, Alabama. As a 23-year-old college student with no criminal record, Aaron had introduced a classmate to a drug dealer he knew from high school. Aaron was neither a buyer nor seller of drugs, but was present at drug transactions and was paid $1,500 by the dealer. Several in the group were charged with a drug conspiracy offence for sale of powder and crack cocaine, and Aaron’s friends testified against him in exchange for reduced sentences. In 1993, Aaron was sentenced to three life prison terms. Over the course of two decades in prison, Aaron studied religion, economics and photography, and worked in a prison textiles factory. After several rejections of his application for a commutation, Aaron was finally granted release by President Obama in 2013 after serving 20 years in prison (Currier 2013).

This case is but a window into the reality of life imprisonment in the United States. The nearly four-decade historic rise in the use of incarceration in the US also produced a vast expansion of the imposition of life sentences, to a degree hitherto unknown in any democratic nation. These developments present profound concerns regarding human rights in the American criminal justice system. But at a moment of potential justice reform and decarceration, the massive use of life imprisonment also raises substantial challenges to prospects for change.

In the present chapter, we explore the American experience of mass incarceration as a backdrop for the overuse of life sentences. Next, we examine the political landscape in the US that has enabled and encouraged states and the federal system to become increasingly punitive, followed by a discussion of the effect of the nation’s overuse of life sentences on the acceptable punishment ranges for less serious crimes. In the fourth section, we document the human rights violations that accompany the use of life sentences with no possibility for parole in the US; we then examine the prospects for criminal justice reform more broadly and, finally, assess the challenges to eliminating America’s mass incarceration problem presented by the continued reliance on life sentences.

II.MASS IMPRISONMENT AND THE MASSIVE USE OF LIFE SENTENCES

Since the early 1970s the US has expanded its incarcerated population at a rate that is unprecedented in US history or that of any other nation. From a prison and jail population of about 330,000 in 1972, the system has bloated to the point of incarcerating 2.2 million persons behind bars as of 2014. The US rate of incarceration of 698 per 100,000 is the highest of any major nation in the world and is more than five times the rate of most industrialised nations (Walmsley 2015). While a number of states have achieved substantial reductions in their prison populations in recent years and the overall scale of imprisonment has now essentially stabilised, it is not declining to any significant degree.

While the policy, fiscal and moral issues surrounding mass incarceration have achieved increasing prominence in public discourse, issues regarding long-term prisoners and those convicted of serious offences have engendered little public discussion. To this day, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the well-regarded data analysis section of the Department of Justice, has not issued any comprehensive data on the number of individuals serving life or long-term sentences.

Estimates of the number of people serving life prison terms in the US have been provided in several policy reports published by The Sentencing Project since 2004 (Mauer, King and Young 2004; Nellis and King 2009; Nellis 2013). Based on data provided by state and federal departments of corrections, these analyses present a portrait of the scale of life imprisonment in the US, along with trend data and demographic details.

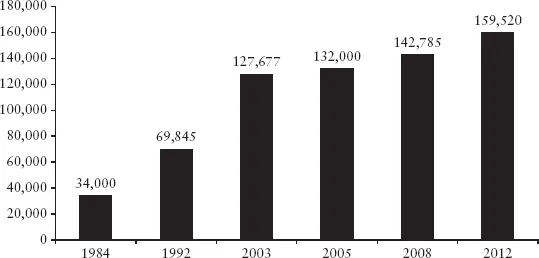

As of 2012, there were 159,520 people serving a life sentence in the US. This constitutes a remarkable one out of every nine (11 per cent) imprisoned persons in the country. As seen in Figure 1.1, the increase in the number of life sentence prisoners has also been dramatic, rising from an estimated 34,000 in 1984.

Figure 1.1:The Expansion of Life Sentences in the United States, 1984–2012

Sources: American Correctional Association (1984); Maguire, Pastore and Flanagan (1993); Mauer, King and Young (2004); Liptak (2005); Nellis and King (2009); Nellis (2013).

The rate at which offenders are sentenced to life imprisonment varies considerably across the country. As at 2012, in seven states—Alabama, California, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Utah and Washington—more than 15 per cent of the prison population is sentenced to life. At the lower end of the scale, five states—Arizona, Connecticut, Indiana, Maine and Montana—have less than 4 per cent of their prison population serving life (Nellis 2013: 6). In addition, Alaska is the only state without a life sentence provision, though de facto life sentences are used.1

The US sentencing system is also marked by a strong tendency to impose not only life sentences, but increasingly sentences of life without the possibility of parole (LWOP). An estimated 49,000 persons were serving such sentences as of 2012, representing nearly a third of all life sentences (Nellis 2013: 6). With the exception of just a handful of persons who gain executive clemency after serving decades in prison, all of these individuals can expect to die in prison.

It is also notable that the scale of increase of both life sentences overall and LWOP sentences has been rising markedly in recent years, even as the overall institutional population is stabilising. From just 2008 to 2012 there was a 12 per cent rise in the number of persons serving a life sentence, and a 22 per cent rise in those serving LWOP sentences (Nellis 2013: 13).

The US is also unique among world nations in allowing the imposition of LWOP sentences for juveniles under the age of 18. While such cases are virtually unheard of elsewhere in the world, there are about 2,500 such cases in the US today (Nellis 2013: 11). As a consequence of two significant decisions by the US Supreme Court in 2010 and 2012 those numbers can be expected to decline somewhat in the coming years as prisoners in some states will qualify for resentencing to a term less than life (Graham v Florida 2010; Miller v Alabama 2012).

We note as well that there is an undetermined, but likely substantial, number of people serving ‘virtual life’ sentences in the US (see Henry 2012). These are individuals sentenced to prison terms of at least 50 years which, when imposed on a 30-year-old offender, could also equate to life imprisonment.2 One example of the means by which an ‘alternative’ to a life sentence can be imposed was the action by the governor of the state of Iowa following the US Supreme Court’s striking down the imposition of mandatory LWOP terms for juveniles. In order to avoid a situation whereby most of the affected individuals might apply for a resentencing, the governor commuted the life sentences, but established a 60-year minimum term before an individual could be considered for parole. It will be the rare person serving one of these terms who will ever be released from prison.

As is true of incarceration overall in the US, the population of individuals serving life sentences is heavily skewed by race and class (Nellis 2013). Nearly half (47 per cent) of life sentence prisoners are African American, including 62 per cent of those in the federal prison system. In some states, the percentage of lifers who are black is quite dramatic, as high as 77 per cent in Maryland and 72 per cent in Georgia (Nellis 2013: 9).

America’s longstanding issues of race and class are enmeshed with its punitiveness. While African Americans have higher arrest rates for violent crimes than other groups, the degree of punishment imposed for such offences is at least in part a function of the public perception of criminal involvement. In a 2002 survey, for example, Ted Chiricos and colleagues studied various crime policy preferences to determine whether one’s own race was a predictor in policy views, net of other relevant factors (Chiricos, Welch and Gertz 2004). The researchers gauged public preferences for the following policies: ‘making sentences more severe for all crimes’; ‘executing more murderers’; ‘making prisoners work on chain gangs’; ‘taking away television and recreation privileges from prisoners’; and ‘locking up more juvenile offenders’. Their findings showed that whites who attributed higher proportions of serious crime to African Americans were significantly more likely to support punitive policies. This was not the case for blacks or Hispanics. More recent research in this area found similar results (Semukhina and Demidov 2011).

III.LIFE IMPRISONMENT IN THE US AS AN OUTGROWTH OF THE AMERICAN POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT

The massive imposition of life sentences in the US is both an outgrowth of the American commitment to punishment and, in turn, a major contributor to the scale of punishment. While there has been much scholarly focus on the four-decade rise in incarceration in the US (Clear and Frost 2013; Mauer 2006; National Research Council 2014), there has been relatively little attention focused on the fact that US rates of incarceration were higher than in comparable nations even prior to these developments.

At the inception of the prison expansion in 1972 the rate of incarceration in prison and jail was about 160 per 100,000 (Mauer 2006: 17). This rate was about two-to-three times that of most industrialised nations. So while the scale of the differential between the US and other nations has risen in recent decades, it is also the case that the US maintained a larger commitment to punishment even before the historic increase.

This approach to punishment helps us to understand the development of mass incarceration since that time. The comprehensive assessment of these developments by the National Research Council (2014) concluded that mass incarceration was essentially a product of changes in policy, not crime rates, over a period of several decades:

The empirical portrait … points strongly to the role of changes in criminal justice policy in the emergence of historically and comparatively unprecedented levels of penal confinement. As a result of the lengthening of sentences and greatly expanded drug law enforcement and imprisonment for drug offences, criminal defendants became more likely to be sentenced to prison and remain there significantly longer than in the past. (National Research Council 2014: 34)

Why, though, has there been such a uniquely American zeal to punish? Varying theories point to such features as the impact of the individualised social structure, or ‘frontier mentality’, in the US, in comparison to the greater social welfare orientation in European nations (Sarat and Martschukat 2011); the politicised nature of American criminal justice, including elected prosecutors and judges, as opposed to the civil service structure of those positions in most industrialised nations (Tonry 2013); and the history and legacy of racism in American society, as played out through the social control of the justice system (Alexander 2012; Garland 2001).

Anthony Doob and Cheryl Marie Webster also note the relationship between high incarceration rates and other societal social values, such as minimum wage policies (Doob and Webster 2014; see also Sutton 2000; Western 2006). They point to a body of research which demonstrates that nations with low rates of economic disparity and generous social welfare policies also generally maintain low imprisonment rates.

IV.LIFE IMPRISONMENT EXACERBATES THE SEVERITY OF THE PUNISHMENT ENVIRONMENT IN THE US

While the extensive use of life imprisonment, along with the death penalty, is in many ways an outgrowth of the American commitment to punishment, it also in turn influences the scale of punishment and the development of mass incarceration. The primary means by which this takes place is through the structure of the sentencing system.

Sentencing systems, whether determinate, indeterminate, or a mix of the two, are generally proportional in structure. That is, the key factors determining the degree of punishment to be imposed in a given case are the severity of the offence and the prior record of the offender. So murder is punished more harshly than robbery, which in turn is punished more harshly than burglary, and so on.

In looking at other industrialised nations, virtually all have repealed capital punishment and only impose life imprisonment sparingly. The contrast to sentencing policies in the US can perhaps be seen most dramatically in the sentencing structure in Norway, a nation with a rate of incarceration of about 71 per 100,000 (Walmsley 2015). Following the tragic massacre of 77 people (including 69 individuals on the island of Utøya, many of whom were children) by Anders Behring Breivik in 2011, he was sentenced to the maximum penalty for that crime, 21 years of imprisonment (Appleton 2014).3

To place some perspective on this, Weldon Angelos was a 24-year-old music producer in the state of Utah who was convicted of three separate sales of marijuana of about $300 each to an undercover officer in 2002. On each of these occasions he was in possession of a weapon, which he did not use nor threaten to use. Because of the mandatory sentences that apply to many federal drug and gun crimes, Angelos was sentenced to serve 55 years in prison. At the time of sentencing, Judge Paul Cassell, a self-described conservative Republican, stated:

The court believes that to sentence Mr. Angelos to prison for the rest of his life is unjust, cruel, and even irrational … It is also far in excess of the sentence imposed for such serious crimes as aircraft hijacking, second-degree murder, espionage, kidnapping, aggravated assault, and rape. … To correct what appears to be an unjust sentence, the court also calls on the President to commute...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- List of Figures, Tables and Annexes

- Introduction

- Part I: The Challenge of ‘Life’ in the Americas

- Part II: Life without Parole around the World

- Part III: Life Imprisonment and the European Convention of Human Rights

- Part IV: Countries without Life Imprisonment

- Part V: The (Re)introduction of Life Imprisonment

- Part VI: Life Imprisonment and Preventive Detention

- Index

- Copyright Page