eBook - ePub

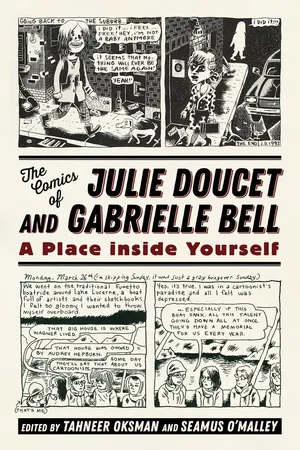

The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell

A Place inside Yourself

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Winner of the 2020 Comics Studies Society Edited Book Prize

Contributions by Kylie Cardell, Aaron Cometbus, Margaret Galvan, Sarah Hildebrand, Frederik Byrn Køhlert, Tahneer Oksman, Seamus O'Malley, Annie Mok, Dan Nadel, Natalie Pendergast, Sarah Richardson, Jessica Stark, and James Yeh

In a self-reflexive way, Julie Doucet's and Gabrielle Bell's comics, though often autobiographical, defy easy categorization. In this volume, editors Tahneer Oksman and Seamus O'Malley regard Doucet's and Bell's art as actively feminist, not only because they offer women's perspectives, but because they do so by provocatively bringing up the complicated, multivalent frameworks of such engagements. While each artist has a unique perspective, style, and worldview, the essays in this book investigate their shared investments in formal innovation and experimentation, and in playing with questions of the autobiographical, the fantastic, and the spaces in between.

Doucet is a Canadian underground cartoonist, known for her autobiographical works such as Dirty Plotte and My New York Diary. Meanwhile, Bell is a British American cartoonist best known for her intensely introspective semiautobiographical comics and graphic memoirs, such as the Lucky series and Cecil and Jordan in New York. By pairing Doucet alongside Bell, the book recognizes the significance of female networks, and the social and cultural connections, associations, and conditions that shape every work of art.

In addition to original essays, this volume republishes interviews with the artists. By reading Doucet's and Bell's comics together in this volume housed in a series devoted to single-creator studies, the book shows how, despite the importance of finding "a place inside yourself" to create, this space seems always for better or worse a shared space culled from and subject to surrounding lives, experiences, and subjectivities.

Contributions by Kylie Cardell, Aaron Cometbus, Margaret Galvan, Sarah Hildebrand, Frederik Byrn Køhlert, Tahneer Oksman, Seamus O'Malley, Annie Mok, Dan Nadel, Natalie Pendergast, Sarah Richardson, Jessica Stark, and James Yeh

In a self-reflexive way, Julie Doucet's and Gabrielle Bell's comics, though often autobiographical, defy easy categorization. In this volume, editors Tahneer Oksman and Seamus O'Malley regard Doucet's and Bell's art as actively feminist, not only because they offer women's perspectives, but because they do so by provocatively bringing up the complicated, multivalent frameworks of such engagements. While each artist has a unique perspective, style, and worldview, the essays in this book investigate their shared investments in formal innovation and experimentation, and in playing with questions of the autobiographical, the fantastic, and the spaces in between.

Doucet is a Canadian underground cartoonist, known for her autobiographical works such as Dirty Plotte and My New York Diary. Meanwhile, Bell is a British American cartoonist best known for her intensely introspective semiautobiographical comics and graphic memoirs, such as the Lucky series and Cecil and Jordan in New York. By pairing Doucet alongside Bell, the book recognizes the significance of female networks, and the social and cultural connections, associations, and conditions that shape every work of art.

In addition to original essays, this volume republishes interviews with the artists. By reading Doucet's and Bell's comics together in this volume housed in a series devoted to single-creator studies, the book shows how, despite the importance of finding "a place inside yourself" to create, this space seems always for better or worse a shared space culled from and subject to surrounding lives, experiences, and subjectivities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell by Tahneer Oksman,Seamus O'Malley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Letteratura & Critica letteraria di fumetti e graphic novel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

A Shared Space

TAHNEER OKSMAN

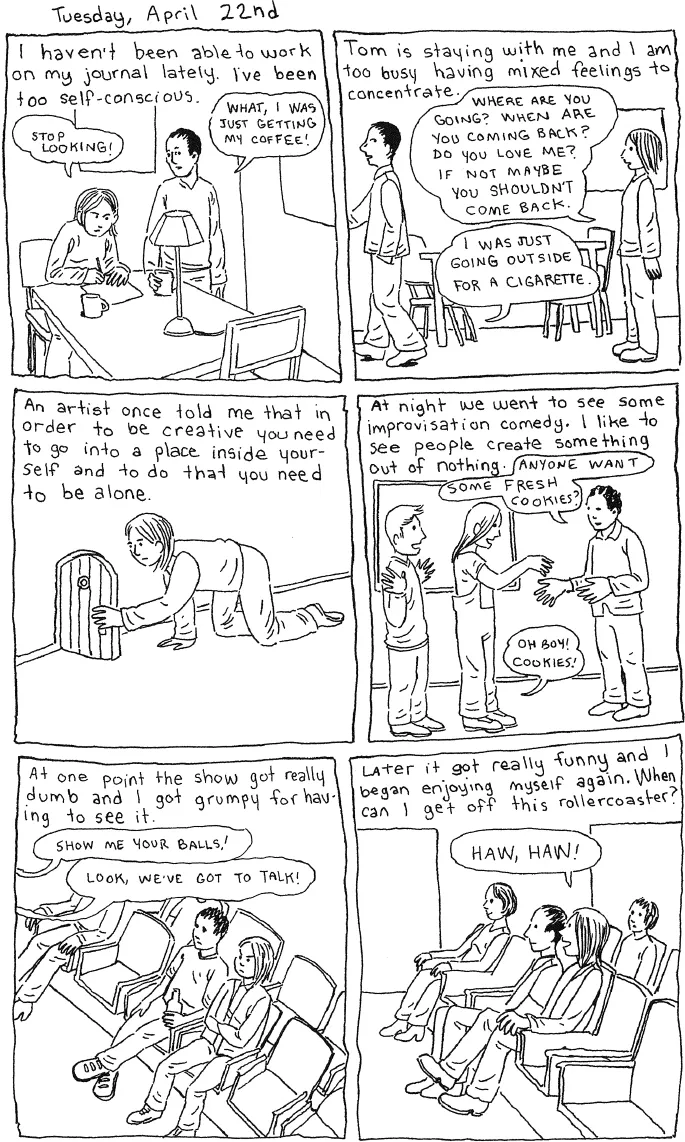

Early on in Lucky (2006), a collection of autobiographical comics, Gabrielle Bell draws a journal entry in which her persona laments having difficulty getting to work, riddled as she is with “mixed feelings” and a sense of being “too self-conscious” (7). Two panels later, she is pictured perched on hands and knees, pulling open a disproportionately small, striped door, as if she were embarked on an Alice-in-Wonderland adventure (Figure 1). The narrative above the image reads, “An artist once told me that in order to be creative you need to go into a place inside yourself and to do that you need to be alone.” Ironically, Gabrielle is not drawn alone in any of the other five panels that make up the page, in which she endures a “rollercoaster” of feelings in the company of others as the outside world pulls her from her work desk. Nor is the journal itself meant to be a solitary experience; here, as elsewhere, we, her readers, are clearly invited to enter into Bell’s self-chronicling project.

Along with Julie Doucet, an artist Bell has referred to as a “foremost influence,” Bell’s comics page is an exploration of this very tension: between the presumably solitary nature of one’s internal, creative-making world and the social, responsive, and thus apparently creatively stifling atmosphere of the external world (Cometbus). If, as Sarah Ahmed puts it, “[a] masculinist model of creativity is premised on withdrawal,” these artists reflect the productive consequences of probing such a paradigm, as their creations scrutinize and ultimately challenge the problematic notion of the artist, or even the individual artwork, as an island (217). Throughout their oeuvres, embedded in their designs, styles, stories, and lines, we witness an aesthetics of resistance, a kind of wariness—or weariness—almost always following, or followed by, a swelling, forceful energy.

Figure 1. Page from Lucky.

By exploring the works of these two contemporary cartoonists together in this edited volume housed in a series devoted to single-creator studies, my co-editor, Seamus O’Malley, and I hope to show how, despite the importance of finding “a place inside yourself” in order to create, this space is always, for better or worse, also a shared space, culled from, and subject to, surrounding lives, experiences, and subjectivities. Reading their bodies of work alongside each other is a way of honoring the feminist legacy of connection and engagement, an intervention that takes as its premise that even when we are most alone we are still connected to, and in conversation with, the world around us.

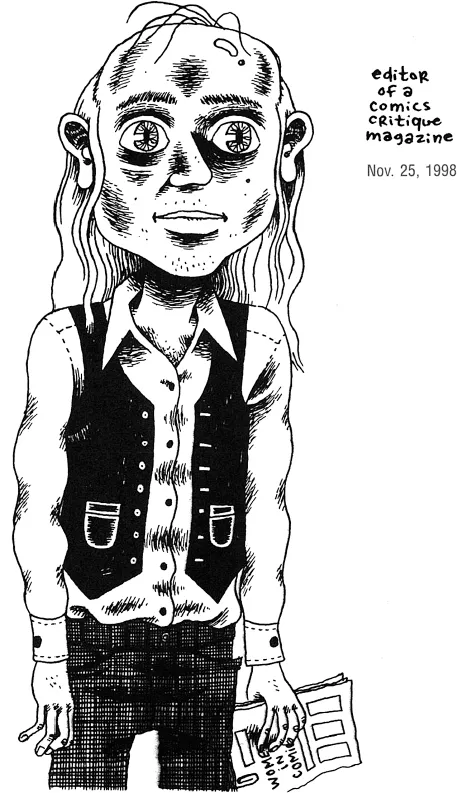

A household name, by now, in alternative comics fan communities who started publishing in the late 1980s, Julie Doucet, an often autobiographical cartoonist who famously left comics at the turn of the century, frequently depicted herself towards the end of that run, both via her drawn personas and in interviews, as an outsider, or someone who did not always feel at home in the world of comics. “I don’t care too much about the comic crowd,” Doucet told Andrea Juno in an extensive interview published in Juno’s notable collection, Dangerous drawings: interviews with comix & graphix artists (1997). “I’m completely sick of them…. I just can’t relate to that scene anymore” (65). In a series called “Men of Our Times,” drawn in 1997 and 1998, Doucet presents portraits satirizing the comics industry.1 Her collection includes, as she notes in its contents: “one director of a comic art museum,” “eight comic artists,” “three fan-boys,” “two publishers,” “two editors of magazines specialized in comic-art,” “one journalist,” “one concierge,” “one grand-father,” “one stranger,” and “six discouraged girls” (Figure 2; Long Time Relationship). Only the final six images, cordoned off in a “Ladies Section” that ends with a self-portrait of the artist holding a glass of wine and shedding a heavy tear, are illustrations of women.

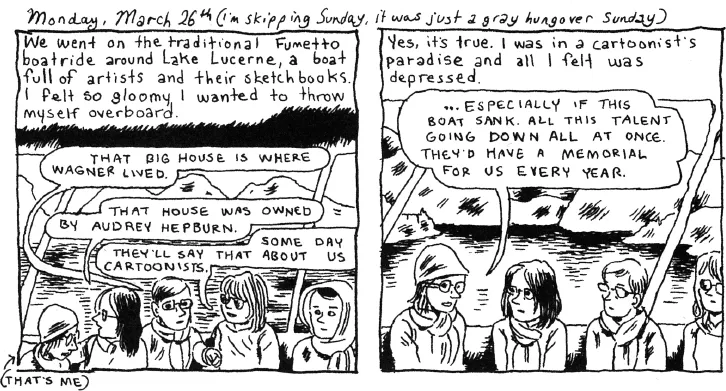

Though her renunciation of certain aspects of comics culture is more ambivalent, Bell too has depicted herself as not always completely in sync with that world, whether socially, professionally, stylistically, or even affectively. Speaking in a 2016 interview with Aaron Cometbus, republished in full in this volume, Bell explained her move out of New York City as an expression of that anxiety: “I was trying to get away from all the cartoonists when I moved, but now I miss the cartoonists.”2 As with Doucet, despite her own publishing successes creating in this medium—she has issued five books in addition to countless shorter pieces published in significant online and print venues—Bell does not always seem to easily identify with it. Even in her many comics diaries picturing her adventures with other notable cartoonists at comics festivals and events, she often depicts herself as feeling out of place or uncomfortable (Figure 3; Truth is Fragmentary 66). Her inspirations and passions, too, as she recounts them both in and out of her work, do not always easily align with her chosen vocation. “I’m not so obsessive about comics, actually,” Bell states in a 2005 interview in response to the question of getting started in her career (Groth). “I don’t really read that many comics as much as I would like to. I’ve always been more interested in novels and movies. I’ve often been really impatient with most comics.”3

Figure 2. Page from “Men of Our Times” in Long Time Relationship.

In addition to the shared perspective of being industry outsiders looking in, the two cartoonists’ approaches and styles are also recognizably related, as Douglas Wolk notes when he includes Bell as part of a cohort of cartoonists at least “ideologically” aligned with a “rough wave” aesthetic (367). The movement, which he traces back to Doucet, marking her, along with S. Clay Wilson, as one of its two “godparents,” is for him today characterized by “the anti-Hollywood narrative, anti-representational, labor-intensive, make-it-nasty tendencies of contemporary visual art” (367). Wolk groups artists including Gabrielle Bell alongside Anders Nilsen, Marc Bell, Brian Chippendale, and Andrice Arp, as invested in “experimenting with styles that are deliberately difficult, going beyond the unpretty cartooning of the ’80s and ’90s art-comics scene” to a range of approaches that include “storytelling techniques that hurl conventional plot dynamics out the window” (366, 367). Both Doucet and Bell also frequently utilize more conventional layout schemes, even as they play with narrative form and tempo, the amount of empty space left on the page, the dynamic between words and pictures, and the architecture of individual panels. Additionally, despite their wide-ranging output, both cartoonists have often been known for their explorations of the autobiographical, a preoccupation that has both attracted critics and fans as well as, at times, created misreadings of their texts.

Figure 3. Two panels from Truth is Fragmentary.

Despite these commonalities, Bell, unlike Doucet, has singularly concentrated, at least for now, on publishing comics. In fact, she has maintained a steady output with some of the best known independent comics-focused publishers, including Alternative Comics, Uncivilized Books, and Drawn & Quarterly, since her first collection of originally self-published works was published as When I’m Old and Other Stories (2003). Bell’s immersion in a world that she frequently portrays, in interviews as in her comics, as alienating and isolating sets a compelling contrast to Doucet’s eventual, if potentially reversible, renunciation of comics. But reading these two cartoonists alongside each other ultimately reveals how their professions and portfolios have followed paths more similar than not, with “burning out,” for example, cited by each as a consequence of engagement, a form of collateral damage.4 In a brief 2014 profile on Julie Doucet published in Artforum, Hillary Chute describes her as having “not so much left comics as moved to the far edges” (“Hillary Chute on Julie Doucet”). Exploring Bell’s comics in the context of Doucet’s, and vice versa, reveals how in fact both of these artists have spent certain parts of their careers composing along the “edges,” each carefully negotiating, prodding, and stimulating an art and industry that often compels them to situate themselves as at a distance.

“Julie Doucet is the female Crumb. Discuss.” So begins “Strip Teaser,” a 2001 review essay of Doucet’s work published in the Village Voice (Press). Calling Montreal-born Doucet “the female Crumb” is an act that ironically hints at the very assumptions and strictures that convinced her, two years before the review was published, to quit the comics business.5 In describing Doucet as the female Crumb, this critic calls attention not only to the formal attraction of her clean, beautiful lines (it is, after all, meant as a compliment), but also to the juxtaposition between that aesthetic and the ostensibly confessional, no-holds-barred aspects of her comics works, which engage with everything from the unruly, leaky, and abject nature of her alter ego’s plotte (Québec French slang for female genitalia) to her unadulterated sexual experiences and fantasies. As in Robert Crumb’s comics, the combination often unsettles readers in powerful ways.

Of course, Doucet is the so-called female Crumb, because Crumb does not engage with tampons or catcalls or the loss of a girl’s virginity—at least not from the point of view of that girl. The Village Voice piece goes on to establish Doucet’s foray into comics as directly evolving from her reading of his works: “Back in the late ’80s, when grunge and underground were terms of endearment, a 21-year-old college girl from Montreal read a Robert Crumb cartoon translated into Québécois French. Something stirred. A year later, Julie Doucet self-published her first comic—a miniature version of Dirty Plotte, the series that would make her a cult heroine.” This oversimplified account misrepresents Doucet’s particular history and point of view, one that shows her to be far from, simply, a convenient analogue to a more familiar male reference point. In that Juno interview, published four years before the Voice piece, Doucet dispenses her own different story of how she got her start in comics:

I grew up in suburban Montreal, but studied fine art at a university in the city. I met some guys there who were putting out a fanzine. Since I already had a really naïve and cartoony style of drawing, they asked me if I’d drawn any comics. This is how I was first published, when I was 22 or 23 years old. (57)

This version of her early ascent into comics points to an incongruity that winds through her professional trajectory, at least in her telling of it: the often simultaneously mindful and unexpected progression of her career. She represents herself as almost accidentally having fallen into the world of comics (“I met some guys”), while acknowledging, by way of describing her “cartoony” drawing style, having always been connected to this practice, even before the official, and unofficial, world of comics publishing entered into her life firsthand. In fact, in the same interview, she remarks that she “grew up with comics,” listing as early reading experiences “Tintin, Astérix, Lucky Luke, the regular, mainstream French-European comics.” It was only “[m]uch later,” she adds, “at university, [that] I was introduced to American underground comics.” Almost a decade later, on the other end of that narrative, she notes in a 2010 interview the irony of having quit the comics industry only to find herself living off works published in what had become, for her, an anachronous mode: “I’m making more money with comics now than when I was drawing them” (Moore, “Julie Doucet”).

For Doucet—and, we shall see, to some extent for Bell as well—her foray into the comics industry, the widespread success that followed, and the aftermath to that success have been accompanied by a persistent sense of unease, tension, and occasional disappointment. This somewhat paradoxical disquiet—she is, after all, in North American and European comics circles, an almost universally agreed-upon “cult heroine”—is not a position that can easily be tracked, though it certainly echoes her designation as “the female Crumb.”6 In terms of her shifting aesthetic, her social and cultural ties, and the subjects she engages with, Doucet persistently resists, against all odds, the very modes of categorization and comparison that have largely dominated the record of her success, and most prominently the labels of “confessional” and “cartoonist.” “Her stories are so honest that they could be mistaken for a documentary about growing up in Montreal,” writes one journalist in a 1999 article in the Canadian English-language newspaper, National Post (Chevalier). A more recent 2008 review of 365 Days: A Diary (2007), a book that includes daily entries tracking a year in her life, told in handwritten prose, illustrations, doodles, and collage cutouts, laments Doucet’s turn to what the Bookforum reviewer Jessa Crispin describes as a narrative that is “self-protective” and “infuriatingly shallow.” As Crispin explains of Doucet’s shift from more traditionally recognizable “confessional” comics to the experimental artistic forms that have shaped her output since her 1999 decision to quit comics, “It’s a shame that, for Doucet, gaining stability has meant losing dramatic tension and narrative drive in her work…. Here’s hoping that when she finishes her metamorphosis, she’ll let readers back into her world.”7 As in the ascription of Doucet as a di...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: A Shared Space

- Section One: Genealogies

- Section Two: Drawing Across Autobiography

- Section Three: Transgressive Aesthetics

- Section Four: Communal Visions

- Interviews

- Contributor Biographies

- Index