![]()

Chapter 1

“Then I Could Have a Real Papa and Mama like Other Kids”

Little Orphan Annie, the Orphan Girl Formula, and the Nanny State

In the apt words of Worth Gatewood, Little Orphan Annie “has long since ceased to be simply a comic-strip figure…. She has become part of the American myth” (viii). For almost a century, the spunky eleven-year-old was one of the nation’s most beloved, recognizable, and enduring characters. Created by Harold Gray and debuting in the New York Daily News on August 5, 1924, the Little Orphan Annie comic “reached the zenith of its popularity during the Thirties, when more than 500 newspapers in North America subscribed to it” (Smith, 23). For decades, Gray’s creation “would be in the top five favorite comic strips in every poll conducted among newspaper readers” (Mullaney and Canwell, 5). As Maria Mazzenga has noted, the strip ranks among the most commercially successful comics of the twentieth century (431–34).

The popularity of Little Orphan Annie in US print culture precipitated her appearance in other mediums. From 1930 to 1940, Annie’s exploits formed the basis for a wildly successful syndicated radio program. “Adventure Time with Orphan Annie held an audience of children estimated at six million … five evenings a week, from 5:45 to 6PM, EST” (Smith, 39). In addition, in 1976, the comic obtained a whole new cultural life, along with a cadre of fans, when it was adapted as a Broadway musical. Over the past ninety years, Harold Gray’s moppet has also appeared in a variety of feature-length Hollywood films: first in 1932; then again in 1938; next, and by far most famously, in 1982; and finally, most recently, in 2014. Throughout this span, Annie has enjoyed a strong presence in American material culture. Her likeness has appeared on a wide array of consumer items, ranging from toys, clothes, books, and dolls to bedding, school supplies, jewelry, and dishes. Given both the diversity of these objects and their ubiquity, Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell called Little Orphan Annie nothing less than “an icon of American culture. Even those who’ve never read the comic strip are keenly aware of the spunky orphan, her loveable mutt Sandy, and her adoptive benefactor, Oliver ‘Daddy’ Warbucks” (5).

In what has become an oft-repeated anecdote about the origins of Little Orphan Annie, when Harold Gray first conceived of his new comic strip character, she was a he. As Bruce Smith has recounted, “Gray titled the strip ‘Little Orphan Otto,’ worked up a dozen sketches of a boy in various poses, and showed them to [Joseph Medill] Patterson,” Gray’s editor at the Chicago Tribune (9). Having pitched ideas for numerous other strips over the years, Gray “was braced for the familiar step of rejection” (9). Much to Gray’s surprise, however, Patterson liked the idea, “but with one important alteration. ‘The kid looks like a pansy to me,’ the Captain said with a scowl. ‘Put a skirt on him and we’ll call him ‘Little Orphan Annie’” (9).1

With this change, Gray’s character joined a long tradition of orphan girls in American popular culture. As Claudia Nelson, Joe Sutliff Sanders, and Carol Singley have all written, young girls who were “invalids, orphans, or waifs” (Sanders, 145) constituted some of the most beloved protagonists in novels, poems, and films from the middle of the nineteenth century through the opening decades of the twentieth. Given this context, when Joseph Medill Patterson instructed Harold Gray to “put a skirt on” Little Orphan Otto and thereby create Little Orphan Annie, he was not encouraging his cartoonist to engage in an iconoclastic act. Instead he was having Harold Gray’s creation participate in an established cultural phenomenon.

In this chapter, I explore this fundamental but underexamined aspect of Harold Gray’s newspaper strip: Little Orphan Annie as an orphan girl story. Far from an incidental detail about its original historical context, the tradition serves as both a creative starting point for the comic and its critical end point. So many of the stories, characters, and themes in Little Orphan Annie arise from the orphan girl story and, ultimately, return to it. Placing Little Orphan Annie back in the context of the orphan girl story—and tracing the way in which this phenomenon operates in Gray’s strip—yields new insights about the strip’s connection with popular culture, the factors fueling its success, and its primary artistic kinships.

That said, Little Orphan Annie’s engagement with the orphan girl story is not one of simple participation. The newspaper strip replicates key facets of the formula while it revises others. In so doing, Little Orphan Annie offers a powerful commentary on this well-known genre, along with the larger sociocultural issues that it engages. Orphan girl stories have long been seen as possessing conservative messages that serve to maintain the status quo. The modifications that Little Orphan Annie makes to this tradition, however, serve a far different function. Throughout the comic, these changes challenge hegemonic notions about girlhood and family.

In the same way that Gray’s newspaper strip modifies the orphan girl story to destabilize many of the sociocultural institutions that the formula had long been used to support, the comic also ultimately puts these progressive elements to far different sociopolitical ends. Little Orphan Annie uses orphanhood as a vehicle to critique not simply family ties or legal guardianship in the United States during the 1920s but also another issue that concerned the cartoonist: the nanny state. Annie repeatedly demonstrates that she doesn’t need to be protected, coddled, or taken care of by Daddy Warbucks—and she likewise doesn’t need such treatment by another wealthy, paternalistic benefactor: Uncle Sam.

At this point in criticism about Little Orphan Annie, Harold Gray’s political beliefs are no secret. As the cartoonist famously said, he was a “Republican down to his toenails” (quoted in Smith, 58). Previous discussions about Little Orphan Annie suggest that Gray’s politics surfaced in the comic strip during the 1930s, amid the Great Depression, the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the passage of the New Deal. The discussion that follows both challenges and extends this critical perspective, demonstrating that such elements are present in the comic from the beginning. Gray’s famous character is not just an orphan; she is a case study about the effectiveness of laissez-faire capitalism.

“AND IF IT’S NOT TOO MUCH TROUBLE I’D LIKE A DOLLY TOO—AMEN”: SENTIMENTALITY, SYMPATHY, AND SPIRITUAL UPLIFT

In the apt words of Claudia Mills, “As long as there have been novels about children, there have been novels about orphans” (227). This feature forms one of the most common tropes within both British and American literature. For example, in Great Britain, “The great novelists of the nineteenth century who explored the world of childhood created a gallery of memorable orphan children: Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Jane Eyre, Silas Marner’s Eppie” (Mills, 227). These figures have been just as pervasive in the United States. In examples such as Horatio Alger’s Ragged Dick (1868), Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes (1912), “American literature abounds with orphaned, homeless, destitute, or neglected children” (Singley, 3).

While orphaned children have long been a powerful archetype in the United States, stories featuring orphan girls rose to special prominence in the middle of the nineteenth century. The release of Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World in 1850 inaugurated this trend. The book—which told the story of protagonist Ellen Montgomery, whose mother dies early in the novel and father passes away later in the text—was an “immediate success. The Wide, Wide World went into twenty-two editions in only three years” (Singley, 201).

The best-selling status of Warner’s orphan girl story launched an entire subgenre of narratives along these lines. As Joe Sutliff Sanders has discussed, orphan girl stories constituted some of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed books in the United States for the next seventy years (2–3). Bookended by Susanna Maria Cummins’s The Lamplighter (1854) and L. M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon (1923), titles included E. D. E. N. Southworth’s The Hidden Hand (1859), Louisa May Alcott’s Eight Cousins (1875), Kate Douglas Wiggin’s Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903), Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess (1905), L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908), Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), Eleanor Porter’s Pollyanna (1911), and Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs (1912). These books were beloved by both adults and children during their era—and many remain classics today.2

When Little Orphan Annie debuted in the New York Daily News in 1924, the strip’s original audience would have immediately recognized Annie as participating in this tradition. Even the specific name that Patterson suggested to Gray for his new comic strip announced its connection to the orphan girl tradition: “Little Orphan Annie” was an allusion to the much-loved poem “Little Orphant Annie,” by James Whitcomb Riley (Smith, 3). First published in 1885, Riley’s poem quickly became “an immensely popular piece of the nineteenth century” (Young, 310). In a telling index of the poem’s national appeal, “Little Orphant Annie” was made into a silent film in 1918. Moreover, demonstrating the celebrity status that the poet had attained, the movie featured Riley in a cameo role (Negra, 34).

Harold Gray’s newspaper strip does far more than simply allude to the orphan girl phenomenon via the name of its title character. The comic incorporates some of the genre’s best-known features. From the portrayal of the protagonist as a pitiable figure worthy of sympathy to its presentation of the ways that children can emotionally soften and psychically rejuvenate even the most cantankerous adults, Gray’s character possesses traits that made orphan girl stories so endearing. The success of Little Orphan Annie has often been attributed to the fact that she was a new type of character in American comics. During the 1910s and 1920s, the funny pages overwhelmingly featured male protagonists. As Gray himself once commented, “At the time, some 40 strips were using boys as the main characters; only three were using girls” (quoted in Harvey, “The Orphan’s Epic,” para. 5). Little Orphan Annie crossed the gender line and demonstrated that a girl could carry a strip. The redheaded eleven-year-old may have been a new type of character in US comics, but she was not one in the nation’s print culture. On the contrary, Annie was the continuation of a long literary tradition—and this fact forms a significant and previously overlooked factor to her fame.

• • •

While the specific events of orphan girl stories varied, they all contained the same basic plot. As Diana Loercher Pazicky has written, these narratives featured a white, preadolescent girl who hailed from a respectable middle-class or upper-middle-class Protestant family (xiii–xvi). The narrative commenced with the death of one or both of her parents—or these events transpired just before the start of the action. Regardless of the exact timing of these occurrences, the end result was the same: they rendered the young girl destitute. As readers witness early in the novel, the formerly contented, cherished, and comfortable protagonist is now both penniless and alone. She has lost her family, and as a result, she has lost her financial stability.

This scenario lays the groundwork for a feature that was arguably the essential ingredient of orphan girl stories. In the words of Claudia Mills, the characters in these narratives were “much sentimentalized” (228). Both because the protagonists now found themselves in dire circumstances through no fault of their own and because they hailed from white, middle-class Protestant backgrounds, they were regarded with compassion and empathy rather than blame and condemnation (Pazicky, 149). As a result, from the time of their origins in the mid-nineteenth century through their presence in the early twentieth, orphan girls were intended to elicit readers’ sympathy, not their scorn. Presented as physically alone, economically destitute, and emotionally vulnerable, these characters were “innately pitiable” (“Orphan Stories,” para. 2).

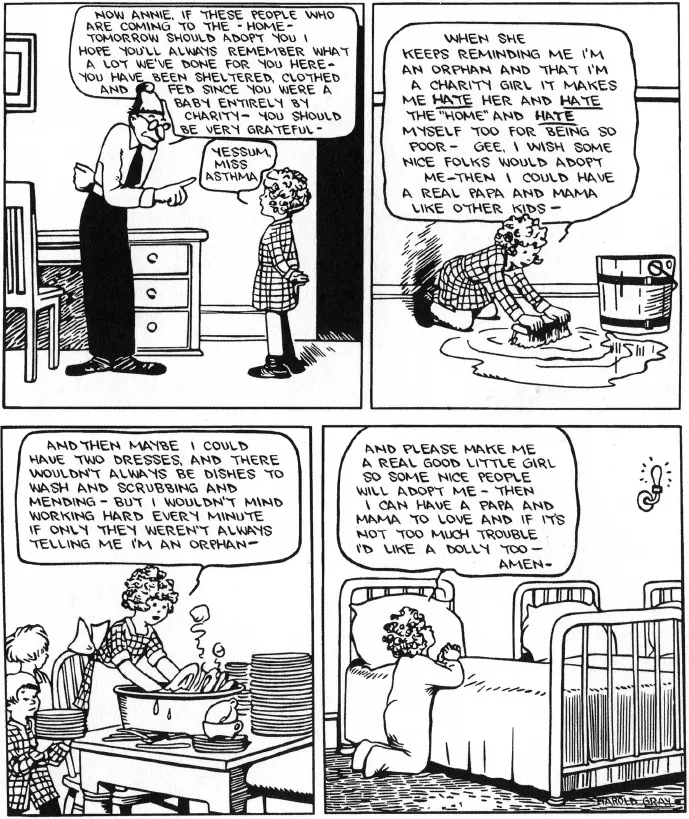

Little Orphan Annie firmly locates itself within this tradition. The comic consistently presents the title character in highly sentimentalized ways that are designed to stir the reader’s emotions—and win his or her sympathy. These features are firmly established in the debut strip (fig. 1.1). The first panel shows an older woman pointing her finger at the young girl and lecturing her: “Now, Annie, if these people who are coming to the ‘home’ tomorrow should adopt you I hope you’ll always remember what a lot we’ve done for you here—you have been sheltered, clothed [and] fed since you were a baby entirely by charity—you should be very grateful” (Gray, 36). Although Annie responds politely—saying only “Yessum, Miss Asthma” (36)—Gray provides an abundance of visual clues to indicate that he does not want his readers to agree with these views. Instead, he wants them to see such comments as cruel and hurtful. Not only does the cartoonist give the caretaker of the orphanage the unflattering name of “Miss Asthma,” but he also presents her in a severe way: she is tall and thin and has her hair pulled up in a tight bun. By contrast, Annie—with her baby doll dress and short ringlets—is a portrait of cherubic beauty and romantic innocence.

The second panel makes these features more explicit. Here Annie is presented in an even more pitiable manner: we see the adorable little girl on her hands and knees, scrubbing the floor with a brush. A wooden bucket of water sits to one side. Of course, this visual imagery alone would elicit strong sympathy. As Viviana Zelizer has documented, beginning in the 1880s and accelerating rapidly in the opening decades of the twentieth century, profound shifts took place in the United States with regard to popular attitudes regarding children’s relationship to labor. In previous generations, young people were seen as possessing measurable economic value, with children working as farmhands, performing domestic chores, and even taking jobs outside the home to bring in wages (Zelizer, 100–101). For both urban and rural families, boys and girls contributed materially and monetarily. Consequently, having children was regarded as a financial asset; they helped to support households, both directly and indirectly (100–101).

In the opening decades of the twentieth century, however, this phenomenon began to change. American society increasingly felt that young people—especially those who were white, native born, and middle class—ought to spend their childhoods playing, not working. Progressive-era reforms steadily took children out of the labor market, while changes in child-rearing practices eliminated chores altogether, cut back on them drastically, or offered monetary compensation for their completion in the form of a weekly allowance. In this way, young people went from being economic assets within families to economic “burdens” on them (Zelizer, 198, 209). Children needed to be clothed, fed, and sheltered—all of which cost money—but they themselves did not contribute. These economically “useless” children, however, were worth this financial sacrifice because they had value in another way: they were emotionally “priceless” (Zelizer, 3). As Zelizer notes, children brought joy, love, and happiness to parents—benefits that defied monetary valuation.

Figure 1.1. The very first Little Orphan Annie comic, August 5, 1924. By Harold Gray.

Although Gray’s Little Orphan Annie takes it name from James Whitcomb Riley’s 1885 poem “Little Orphant Annie,” the relationship that the two characters possess with labor demonstrates the profound shifts that took place between the 1880s and the 1920s. As Claudia Nelson has summarized, Riley’s narrative poem tells the story of a young girl who is “‘bound out’ to earn her own way in the world. In return for room and board, young Annie … serves as maid-of-all-work for a large family” (1). By contrast, in Gray’s comic strip, Annie’s engagement in domestic drudge work—such as scrubbing the floor—is used to elicit sympathy. Rather than showing the white orphan girl rightfully “earning her keep” or usefully “contributing” to a household, the strip shows her being physically exploited and emotionally mistreated. Little girls exist to be loved and cherished by adults—not to be used as free sources of manual labor.

In case any doubts remain about Annie’s opinion of Miss Asthma, a speech bubble makes them perfectly clear. “When she keeps reminding I’m an orphan and that I’m a charity girl it makes me hate her and hate the ‘home’ and hate myself for being so poor,” the protagonist says aloud to herself while scrubbing the floor (Gray, 36). Far from regarding Miss Asthma’s comments about her being grateful for the charity that she has received as blunt pragmatism or even brutal honesty, Annie finds them infuriating. The young girl understandably does not appreciate being reminded that she is a societal burden. Not surprisingly, she longs to find a loving family of her own and leave...