![]()

CHAPTER 1

LAUGHING AT THE BAROQUE: A DRAWING AND SOME TEXTS COMPARED

Susanna Pasquali

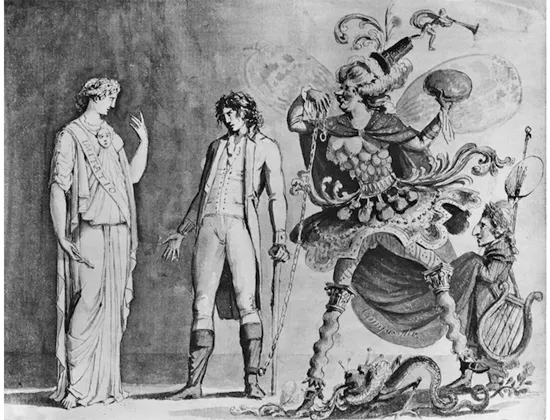

The drawing known as ‘The Artist at the Crossroad’, by the Swiss painter Joseph Anton Koch (1768–1839), is often referred to in art-historical literature despite going missing during the Second World War.1 This sheet, known only from an old black and white photograph (Figure 1.1), is in fact cited and reproduced whenever there is discussion of the figure of the artist and his role in the late eighteenth century. Oskar Bätschmann gave it a detailed analysis in 1997.2 The drawing also registers hits on the Internet and is continuously commented on by users.3 In the present text I aim to address two questions: the relationship of the image with architecture and the derisory tone in which this is represented. In the conclusion I match the drawing against some contemporary architectural literature.

Figure 1.1 Joseph Anton Koch, ‘The Artist at the Crossroad’ , c. 1791, drawing once in the Graphische Sammlung, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart.

The drawing is dated 1791, the year the young artist ran away from the Hohe Carlsschule in Stuttgart, a kind of military academy, where he had been placed through the influence of a patron who had offered to help with his education. In that same year Koch undertook of his own accord a series of journeys, which eventually led him to settle in Rome in 1795.4 There he lived until his death as a recognized painter, in the orbit of the Nazarenes.

Three figures are presented in the drawing: at the centre stands a young man, wearing the clothes of the period, with two personifications either side of him. The figure in front of him – named in Latin in Roman capitals on the diagonal sash over her robe – is Imitatio, and behind him – named in modern italics on the bottom edge of the cloak – stands the personification of the concept of Composthe, a translation of the French composite,5 a depiction of all that is inconsistent in art theory and practice. As has been noted, the young man’s position between the two figures recalls that of ‘Hercules at the crossroad’. An episode, first recounted by the Greek philosopher Prodicus of Ceos and passed on in Xenophon’s Memorabilia, that finds the hero caught between the personifications of vice and virtue.6 Several paintings, including the famous depiction by Annibale Carracci, have centred on the episode, presenting the three figures in a variety of shapes. Here, in Koch’s drawing, the young man is not Hercules but an artist; thus, the choice between evil and good takes the form of an option between an unmistakably baroque art and a ‘new’ art, which looks to the antique and is hence personified by Imitatio. From this identification of the figures Bätschmann goes on, in reference to the opposition between vice and virtue, to add some general considerations on the nature of artistic freedom from the eighteenth century onwards.7 In the light of what has been said so far, it is evident that this drawing has attracted the attention it still enjoys essentially because what it offers is a didactic image of the artist on the verge of casting off the chains of traditional patronage.

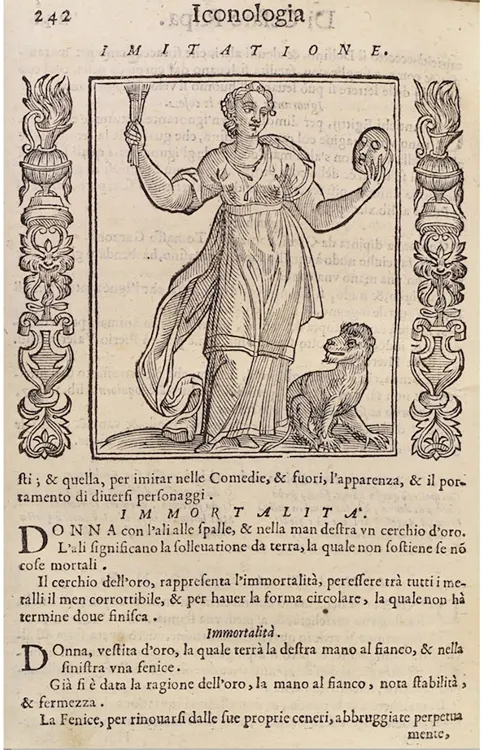

If this is the general picture, I believe this shift from ‘Hercules at the crossroad’ to a new subject, namely the ‘artist at the crossroad’, deserves an analysis that takes into account many of the extraordinary details in the drawing. Previous depictions had set Hercules in a variety of postures but always in the attitude of waiting. In Koch’s drawing the artist is instead represented as a wayfarer, wearing high boots and carrying a walking-stick, who has come to a sudden halt, taken aback in amazement, in an attitude perhaps of non dum dignus (not yet deserving), by the apparition of a female figure modelled on a classical statue. This figure, the personification of the concept of Imitatio, is a simplified version of how she appears in the traditional iconography made popular by, for example, the various editions of the book by Cesare Ripa (Figure 1.2).8 In her right hand, instead of a bundle of brushes she holds just one; furthermore, since Imitatio refers on this occasion to the single art of drawing, the monkey and the theatrical mask, elements that represent the ability to mimic human behaviour,9 are, as one might expect, absent. Therefore, it is mainly through the simple but effective artifice of the writing on the maiden’s robe that the concept is determined.

Figure 1.2 Cesare Ripa, ‘Imitatione’ , from Iconologia overo descrittione dell’imagini universali cavate dall’Antichità et da altri luoghi, 1593.

The young man has come to a sudden halt in his passage, but he is not free: one of his ankles is shackled by a chain, the other end of which is held by the formidable creature behind him. The artist is thus a captive, shown in the moment of his realization that there is an alternative to his situation.

In order to highlight two propositions, I shall focus on the extraordinary figure of the master of his soul. First, the techniques used to represent this figure are altogether different from those adopted in depicting the artist and Imitatio. Here, in fact, are the methods of caricature: a depiction shaped by derision to stir laughter. Portrayal in the form of caricature had been an established artistic practice for centuries; satirical drawings originated in the eighteenth century, in countries where freedom of expression was guaranteed in the periodical press.10 While in the sphere of art there were conventions and constraints on creating an image, the expressive purposes of the new field of the cartoon was relatively free of such limits, offering experimentation with new languages and different technical means. Among the strategies adopted to convey an import, sometimes hinging on entirely abstract concepts, that had to be clearly readable was the insertion of words. The need, in addition, to ensure for the press the reproducibility of a drawing fostered two-dimensional representation without depth. Koch adopts features of the new language that was developing with the freedom of the press for one of its chief purposes: criticism. The Composthe is a mocking evocation of an Ancien Régime patron, by then obsolete but still robust enough to keep the young artist in chains.

If what the young man is fleeing is evident it should, however, be noted that the ensemble is an amalgam of elements and concepts deriving from architecture. One could even say – and this is my second proposition – that the right-hand half of Koch’s sheet is one of the best and most effectively derisive representations of the art of architecture and its features that could be remarked on, very critically, in the late eighteenth century.

What we see in looking at the Composthe is in fact a phantasmal creature, of apparent male sex, amalgamated, as the name implies, out of many elements. In contrast to the young artist’s untrammeled head of hair, the man’s head boasts an extravagant wig and a plumed hat from which a winged Fame escapes. He has two arms, one holding the end of the chain in marked effeminate fashion while the other brandishes an enticing loaf of bread; he is thus portrayed in the act of offering, with a smile, the reward that enslaves. The rest of his body is worked up out of an equally disparate set of oddments. The open cloak displays a torso which is a rendition of that of the Artemis of Ephesus: an antique model, agreed, but certainly not one from classical Greece. The lower part of the garb consists of two overlapping skirts: the first has clusters of incoherent ornaments waving in the breeze; the second, rigid and, therefore, more linked to the forms of architecture, has a mixed geometric outline. It is the man’s legs, though, that constitute the most recognizably architectural element: they are not human limbs but columns, grounded on a pair of shapely shoes. Their trunks are spirals; the capitals – which here function as knees – are Corinthian. These are the recognizable bronze columns of the canopy erected by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in St Peter’s Basilica. They thus refer to very recognizable artistic forms, as well as to an equally precise milieu: the church of Rome. Moreover, from the entirely skewed positioning of the two legs/columns it is clear that the man, botched together out of pieces, is tottering. He would immediately collapse to the ground were he not upheld by the pair of large butterfly wings mounted on his back: an element fragile in itself and destined, by its nature, to be short-lived.

Finally, it should be noted that – on closer examination – Koch’s drawing has more than three characters. The allegory is in fact completed by a kind of dwarf in the act of holding up the tail of his master’s cloak: he is the artist as slave entire. Whether he be poet – the bays with which he is crowned and the lyre – or painter – given the palette, brushes and mahl stick – he is in any case doomed to an obscure and modest destiny. Another creature, a sort of snake furnished with legs and ruff, paws at the ground, heightening the general sense of unease that emanates from the entire right-hand side of the drawing.

Whatever the young Koch’s intentions were in choosing the precise iconographic references for each of the elements making up the odious figure of the Composthe,11 overall he aimed to depict instability preceding collapse. Given the year of its creation, 1791, there is probably reference to the events of the French Revolution, which the young painter was at the time in sympathy with.12 But I want to note here that among the three branches of drawing/painting, sculpture and architecture, the only one capable in a visual representation of suggesting collapse, with immediacy, is architecture: collapse is in fact easily represented through a building that is about to fall down. An edifice thrown up haphazardly or, to adopt the late eighteenth-century term, without a principle that guarantees its solidity is doomed to fall to the ground.

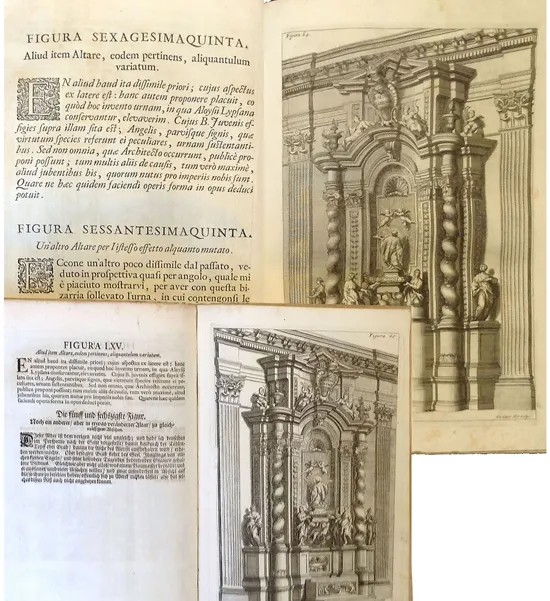

In this context, the choices Koch made to use certain specific architectural elements and not others derives from what the young artist may have known (and hated) while in Stuttgart. It is conceivable that through prints and drawings he was acquainted with the major buildings of Christian Rome and hence the churches of Bernini and Francesco Borromini. It is also possible that he knew, following the models of major buildings of Christian Rome, what had been subsequently built in southern Germany. Above all, it is likely that among the books he studied at the Hohe Carlsschule was Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum by the Jesuit father Andrea Pozzo.13 In learning the rules of perspective, Koch would also have been obliged to reproduce – as advanced exercises – the famous plates in which the more fanciful baroque forms of altars are illustrated (Figures. 1.3 and 1.4).

Figure 1.3 Andrea Pozzo, Perspectiva pictorum et archit...