![]()

Chapter 1

The Community of St Cuthbert

St Cuthbert

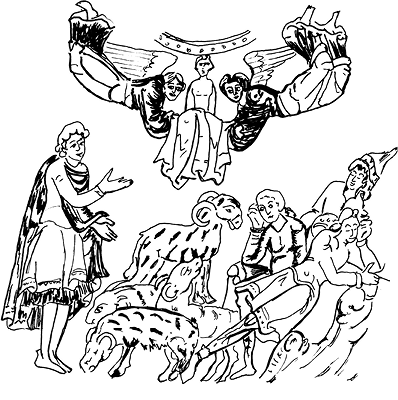

This is the story of Cuthbert as it has come down to us. [1] He was born about ad 635. He kept sheep on the hills near Leader Water, a tributary of the Tweed, now in Scotland, then in the kingdom of Northumbria. In 651 the young shepherd saw a vision of the ascent of the soul of Aidan, bishop of Lindisfarne, and a few days later heard of his death. This made Cuthbert determined to enter a life of prayer, and he joined the nearby abbey of Melrose. [2]

ABOVE: St Cuthbert’s vision of St Aidan’s soul being taken to heaven. Drawing by Rosemary Turner, based on Oxford, University College MS 165 folio 18r.

Melrose Abbey followed customs introduced from Iona, which differed from those of the wider church in a number of ways, the most controversial being the method of calculating the date of Easter. About 658 Abbot Eata and monks from Melrose went to Ripon (Hrypum) to assist the bishop in founding a monastery there. Cuthbert became the guestmaster at Ripon and was said to have entertained an angel sent to test his devotion. [3] However, Ripon was a royal foundation and Aldfrith, sub-king of Deira, favoured the customs practised by the rest of the Western Church. In 661 the king demanded that the Melrose monks either conform to these practices or resign. They were not willing to change their customs and all returned to Melrose. [4] The controversy was finally settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664 and thereafter the Northumbrian Church no longer looked to Iona but to York. Cuthbert seems to have embraced the new customs wholeheartedly, placing the unity of the Christian Church above individual preferences. According to Bede, in later years Cuthbert dissociated himself from those who insisted on keeping to the traditional date of celebrating Easter. [5]

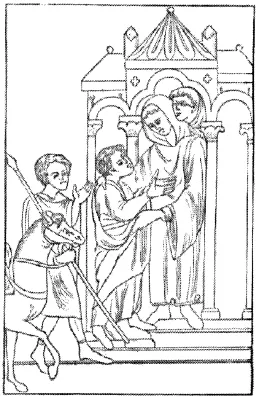

ABOVE: Scenes from the life of St Cuthbert: His arrival at Melrose, appointment as bishop, departure for Farne, and death. From Raine Cuthbert pp. 17, 26, 28, 32. Based on an illuminated manuscript of Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert c.1200 (now London, British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26).

Meanwhile, back at Melrose, Cuthbert humbly submitted himself to the direction of Boisil (Boswell), the prior, who gave him instruction in the scriptures, and set him an example of the holy life. When Boisil declared that he only had a week to live, Cuthbert asked what could be read in seven days and Boisil produced a copy of St John’s gospel in seven parts. They read, discussed and meditated on a part each day until Boisil died on 23 February 662. Cuthbert succeeded him as prior in 664.

Cuthbert was appointed abbot of Lindisfarne in 676 but, after several years in this role, he sailed on to the island of Inner Farne to become a hermit, walling himself in so that during meditations he could see nothing but the sky. His life of solitude ended in 684 when he was appointed bishop of Lindisfarne, after Bishop Eata moved to Hexham. Cuthbert was consecrated on 26 March 685 at York and spent two years travelling the length and breadth of his diocese ministering and preaching. When he realised that his death was imminent he returned to Inner Farne, where he died on 20 March 687. His last request was that, if the monks were ever to leave the island, they would take his bones with them. [6] Cuthbert became famous as a reputed worker of miracles, and both he and Boisil were declared saints.

Cuthbert’s body was taken into St Peter’s Church, Lindisfarne, for burial in a stone sarcophagus on the right-hand side of the altar.

On 20 March 698 Bishop Eadberht of Lindisfarne gave permission to open the grave for Cuthbert’s first translation, which involved the repositioning of the tomb above ground, on the floor of the sanctuary. [7] This revealed his body to be unchanged and incorrupt. The saint was placed in a wooden coffin engraved with angels and apostles, together with a gold and garnet cross, a copy of St John’s gospel and other items. [8] In 737 Ceolwulf, king of Northumbria from 729, entered the abbey as a monk, and on his death on 15 January 764, he too was declared a saint.

ABOVE: Holy Island and remains of the church of Lindisfarne, from MacFarlane & Thomson I p. 153: “From Turner’s England and Wales”.

Post mortem journeys

The area around Lindisfarne was ravaged by the Danes on 7 June 793. [9] The monastery was sacked, many monks were killed, and gold and silver was seized. [10] Following the growing number of Danish attacks between 820 and 830, Bishop Ecgred (Egfrith) of Lindisfarne (830–845) built a church at Norham upon Tweed, dedicating it in honour of St Peter, St Cuthbert and St Ceolwulf. Here were placed the remains of Ceolwulf and, according to some sources, of Cuthbert as well, his shrine perhaps remaining at Norham for about twenty-five years before being returned to Lindisfarne. [11]

Having captured York in 866/7 the Danes began to settle rather than pillage. They set up petty kingdoms, and even appointed an archbishop of York, Wulfhere. [12] The Danish leader Halfdan arrived in 875 to attack Northumbria, and Bishop Eardwulf of Lindisfarne decided to abandon the monastery. The monks removed the body of Cuthbert and wandered for seven (or nine) years, “flying before the face of the barbarians from place to place”. [13] With the body they carried the head of St Oswald, the bones of St Aidan and illuminated manuscripts, including the Lindisfarne Gospels. The porters included Hunred, Stitheard, Edmund and Franco. On their journeys they must have encountered all weathers in all seasons—all endured as an expression of their loyalty and devotion to St Cuthbert.

The patrimony of St Cuthbert had been built up from the late seventh century when in 685 King Ecgfrith gave the Carlisle estates to Lindisfarne and the church there dedicated to St Cuthbert. All gifts were held in common by the hereditary families of the community, with St Cuthbert being the one permanent member. In the wanderings of the community between 875 and 883, it was the possession of the saint’s body that gave corporeal title to the estates. They preserved their integrity and even enhanced the importance of the community.

Gifts included many estates lying between the rivers Tyne and Tees and some in Lothian. Here the community operated an ecclesiastical franchise and, with it, political influence. The people in the area did not consider themselves English or Scots or even Northumbrians—they were the Haliwerfolc—the people of the saint. The quasi-monastic group became known as the congregatio sancti Cuthberti. The congregatio (community) consisted of a dean and seven clerks who, with their families, held the land of St Cuthbert. One of their number was appointed bishop, and associated with them were priests and secular clerks serving the shrine. Although they did not follow a monastic rule, and did not practise celibacy, they followed the church offices they had used at Lindisfarne.

Their journeys took them to Cumbria, from where they intended to seek safety in Ireland. [14] All “gathered at the mouth of the river which is called Derwent [at Workington]. There a ship was prepared for the crossing, the venerable body of the father was placed on it . . . and they steered the ship on a true course towards Ireland”. Suddenly the winds changed and the ship turned on its side, and an ornamented book “fell from it and was carried down to the depths of the sea”. [15] Then one man seized the tiller and steered the ship back towards the shore with the wind behind them. They landed safely, but all bewailed the loss of the book.

Cuthbert then appeared in a vision to Hunred, one of the porters, and ordered that, when the tide went out, they should look for the book. The vision presaged that the monk would find a bridle hanging on a tree and that a horse would appear. Several monks went to look for the book and found that the sea had receded much further than normal. After walking three miles or more towards the sea at Candida casa (probably Whithorn or possibly Whitehaven), they found the book and discovered “the former beauty of its letters and pages, as if it had not been touched by the water at all”. [16] The bridle and horse were found, and used to pull the cart (carrum) bearing the saint’s body back to Northumbria. The brethren stayed in the minster church of Crayke, 15½ miles (25km) east of Ripon for four months, “as if in their own home”. [17]

According to Symeon, St Cuthbert, through a vision to Abbot Eadred, was instrumental in the election of Guthred as the Scandinavian leader and king of York (883–95), bringing a period of tranquillity to the area. The king granted lands between the rivers Tyne and Wear to the congregatio, and the saint’s body was placed in a church in Chester-le-Street, the episcopal see being moved there from Lindisfarne. [18] Here Cuthbert and the community remained for over a century, protected in part by the defensive perimeter of the Roman fort which still existed. [19] It was also a convenient site from which to administer their estates.

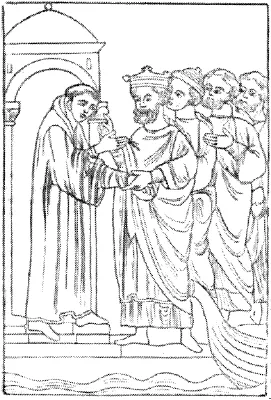

King Athelstan (924–939) made a pilgrimage to St Cuthbert’s Church in Chester-le-Street in 934, [20] and gave many gifts, including a gold and ebony cross, a silver chalice, patens, candelabra, four great bells and service books. One treasure was a Gospel Book. [21] King Edmund (939–946) also visited the shrine and made gifts in about 945. [22]

In 995, Aldhun (Ealdhun), bishop of Chester-le-Street, “was forewarned by a heavenly premonition that he should flee as quickly as possible with the incorrupt body . . . to escape the fury of the Vikings whose arrival was imminent”. [23] The Danes had sacked Bamburgh Castle in 993. [24] Aldhun left with his monks and journeyed south to Ripon. After a stay of a few months the threat of Danish incursions passed and they decided to return to Chester-le-Street. Soon after approaching the river Wear, the coffin became “so heavie, that all the companie that attended the corps could not draw the waine, whereon it lay; by which they perceived so much of St Cuthbert’s minde, that he would not be carried again to Chester”. [25] After fasting for three days it was revealed to them that his perpetual place of rest was to be on an uninhabited piece of land at Dunholme (Durham). The site was on a cliff overlooking a loop of the river Wear, “more beholden to nature for fortification, then [sic] fertilitie”. [26] Here in 995 Bishop Aldhun began clearing the site on the promontory, assisted by Uhtred (Uchtred), earl of Northumbria (c.978–1016), and the entire population of the district between the rivers Coquet and Tees. The seventeenth-century writer, Robert Hegge, whose quaint comments are quoted above, remarks that they were “payd for their pains with expectation of treasure in heaven”. [27]

Durham Cathedral

Aldhun built a shrine with timber and boughs of trees, after which they built a church of “noble workmanship and by no means small in scale . . . Meanwhile the holy body was translated from that little church (mentioned above) into another which was called the White Church, and there it remained for three years while the larger church was being built”. [28] This implies that there were three churches in all. [29] However, the monk Reginald of Durham, who was writing between 1162 and 1173, seems to identify the White Church with the pre-Conquest cathedral. [30] On Sunday 4 September 998 Cuthbert’s body was translated into the east end of Aldhun’s new cathedral.

Reginald informs us that “there were two stone towers, as those who have seen them have reported to us, rising high into the air, the one containing the quire, the other indeed standing at the west end of the church; which, being of wonderful magnitude, carried brazen pinnacles [aerea pinnacula] erected at the summit; and which exceeded as much the wonder as the capacity to admire of all people. Whence they thought a work of similar structure could be built nowhere else; for the reason that, within the bordering limits of the neighbouring region, all the things necessary in nowise could be brought together in like manner in one place”. [31] This refers to the easy supply of stone known as Low Main Post sandstone, which can be cut and sculptured easily and was available from quarries across the river gorge. [32]

At the time of Bishop Aldhun’s death in 1018, “he left only the western tower unfinished, and the church was brought to completion and dedicated by his successor”, Edmund (1020–42). [33] It was slender, with no buttresses, and no offset courses, and Edmund must have “heightened a western porticus of the tenth-century building to form a tower”. [34]

The Danes, who had caused so much devastation in places associated with St Cuthbert, now became worshippers of him in Durham. Cnut (Canute) I, king of Denmark, Norway and England (1016–1035), made a pilgrimage in 1031 by...