![]()

PART ONE

THE CASES

![]()

1

THEORETICAL SAMPLING

This chapter presents the first of three cases in the book, theoretical sampling in grounded theory. Brought together here are methodological accounts spanning nearly 50 years, from the ground-breaking writings of Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in The Discovery of Grounded Theory to much more recent constructivist accounts of grounded theory. The debate about how theoretical sampling should proceed in a piece of research reflects wider methodological debates about how we generate legitimate knowledge about the social world. There is significant diversity discussed in this chapter. The boundaries of the case are defined by an enduring principle of grounded theory approaches within this diversity; theory emerges or is discovered through empirical investigation in which the decisions and implementation of theoretical sampling play a key role.

The discovery of grounded theory

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss were concerned that qualitative research was seen, up to the 1960s in the United States, as largely an enterprise to verify theory. It was often used as a preliminary exploratory effort to provide insight and hypotheses to be tested more rigorously through quantitative methods. These methodologists wanted to show that qualitative research was an enterprise in its own right, capable of providing scientifically robust accounts of the social world. It was not merely a useful precursor to quantitative research. Qualitative research was quite capable, with the right methodological strategies, of generating credible, reliable, and useful theory derived from the qualitative investigation of social interactions.

This theory, Glaser and Strauss (1967: 32) suggest, is a ‘theory of process’ which is an ever-developing and never-perfected product. Through a rigorous method of constant comparison, qualitative research has the ability to generate theory at different levels of generality. Theory may be empirical and substantive, such as patient care, race relations, or the relationships in an organisation. And at a higher level of abstraction, theory can be formal and conceptual social theory, of stigma, deviant behaviours, or authority and power as examples. Together these empirical and formal theories are described by Glaser and Strauss as theories of the middle range, drawing on the work of Robert K. Merton. For Merton (1968: 39) middle-range theory is:

Intermediate to general theories of social systems which are too remote from particular classes of social behaviour, organization and change to account for what is observed and to those detailed orderly descriptions of particulars that are not generalized at all. Middle-range theory involves abstractions, of course, but they are close enough to observed data to be incorporated in propositions that permit empirical testing.

The challenge of the discovery of grounded theory is to systematise a method that allows for a move from empirical observation to the generation of grounded (middle-range) theories and the testing of these theories through empirical observation. These observations are of meaning making, its modification and interpretation between people in their social interactions, a theory of symbolic interaction. Grounded theory, through its investigation of micro-empirical interaction, can discover theory that falls somewhere between ‘“minor working hypotheses” of everyday life and “all inclusive” grand theories’ (Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 33 – emphasis in the original). Instrumental in this discovery and testing of theory is theoretical sampling.

Theoretical sampling

Theoretical sampling is set to work to generate theory in qualitative research through the investigation of the empirical social world. The ‘grounded’ in grounded theory is where the theory is to be found, it is observable and can be interpreted from the behaviour of groups in their everyday social interaction. Herbert Blumer (1978: 38) employs a metaphor of ‘lifting the veils’, which obscure the area of group life that the researcher intends to study. And, in a further metaphor, research is ‘digging deep (in these group lives) through careful study’. Grounded theory respects and stays close to these empirical domains in its research.

To make visible the hard-to-see elements of the empirical social world requires three different dimensions to be addressed in theoretical sampling, according to Glaser and Strauss. These are the controlling influence of emerging theory, the open and theoretically sensitive researcher, and constant comparison.

The controlling influence of emergent theory

Emerging theory is central to processes of theoretical sampling, in which the researcher:

jointly collects, codes, and analyzes … data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them, in order to develop … theory as it emerges (Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 45).

The emphasis here is not only on the methodological process of sampling, but on the central role of this process in the generation of theory. As such, we cannot talk about a theoretical sample. Theoretical sampling can neither be reified to a thing – the identification by researchers of a person, an organisation, document, or research instrument to be sampled – nor can the sample be identified ahead of the research. Instead, the researcher is continuously guided by emerging theory as to where to go next in search of their sample. Structural (or practical) concerns are not the guide to identifying the sample; rather it is the impersonal criteria of emerging theory. As Glaser and Strauss (1967: 47 emphasis in the original) observe:

The basic question in theoretical sampling … is: what groups or subgroups does one turn to next in data collection? And for what theoretical purpose?

In conceptualising the sample in this way a grounded theory approach is distancing itself from the sampling strategies of quantitative researching and from qualitative researchers whose aim is to verify theory. Qualitative researchers, Glaser and Strauss (1967: 30) argue, neither need to ‘know the whole field’, nor are they seeking to represent all the facts in the sample through random selection to ensure every member of a given population has an equal chance of being in the sample. In using theoretical sampling, researchers are not seeking a perfect representation of a concrete situation under study. They are aiming to generate general categories and their properties for general and specific situations and problems, through the acts of writing memos and coding.

Theoretical accounts are tied to particular social phenomena through these memos and codes. But, in emphasising the impersonal way in which theoretical sampling is linked to emergent data, the aim of grounded theory is to remain objective through maintaining a distance between researchers and researched. The account of theoretical sampling in early grounded theory holds to a strongly positivist approach. The characterisation of the researcher as open and theoretically sensitive emphasises this positivism.

The open and theoretically sensitive researcher

An approach to sampling driven forward by emergent theory rather begs the question, where does one begin? The answer lies, in part, in the personality and temperament of the researcher, according to Glaser and Strauss (1967). The grounded theorist is an open and theoretically sensitive researcher. At the outset researchers begin with a partial and unelaborated framework for their research. They will have only a basic outline of the problem to be researched. Researchers must guard against making decisions about what to sample based on a preconceived framework. Openness to discovering concepts in the field is seen as important in ensuring a researcher is able to identify and refine concepts in the early stages of the research. The concepts that inform these early stages of fieldwork sampling are no more than a general sociological knowledge and an understanding of the general problem area of the research. The researcher, Glaser (1978: 44) suggests, can go anywhere, talk and listen to anyone, read anything with nothing more than the overarching problem in their mind, but that researcher must be ‘capable of conceptualisation’.

Researchers capable of doing theoretical sampling are characterised by their receptiveness to emergent theory in the field. A researcher with ‘complete openness is often more receptive to the emergent (theory) than others with a few pre-ideas and perspectives’ (Glaser, 1978: 46), although it is grudgingly accepted that researchers do come to research with some theory. But this theory must be articulated and tested against the empirical data and emergent theory in the research. Most theory is induced through observing, seeing, hearing, reading, and recording particular incidents. The researchers’ open minds are directed towards the coding of observations and the fashioning of emergent theory. The search in early theoretical sampling is for these incidents, which are sampled as they are found. So, for instance, Glaser and Strauss (1967) talk about how they might sit at a nursing station on a hospital ward watching the nursing staff at work, or talk about the research area with key informants. The conversations are broad, the observations general.

At this early stage in the research, it is the sampling and exploration of various incidents to discover underlying uniformities and varying conditions that are of interest. Given that the early research is based on such openness, false starts and starts that do not quite get at the concepts under investigation are inevitable, but these are soon corrected by the constant comparison of theoretical sampling, Glaser and Strauss (1967) assure us.

Constant comparison

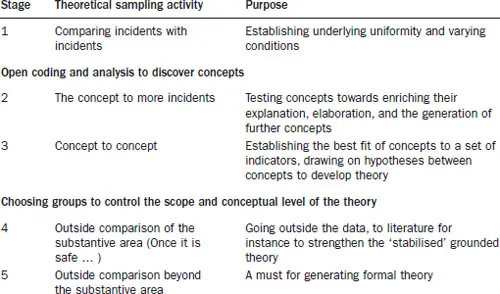

The third controlling influence in theoretical sampling is constant comparison. Table 1.1 identifies each of the different kinds of comparison Glaser and Strauss advocate in theoretical sampling. The linear progression from the sampling of incidents, occurring in the first stage of theoretical sampling, is mediated by theory, described as concepts, as the research progresses. Constant comparison seeks an ever-increasing refinement of emergent theory. Theoretical sampling becomes much more selective, focussing on the concepts identified in the researchers’ emerging theory.

Table 1.1 Constant comparison in theoretical sampling: an overview (after Glaser and Strauss (1967) and Glaser (1978))

The initial focus of constant comparison on observable incidents such as a particular behaviour, like Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) example of the ways in which nurses respond to dying patients for instance, assures ample data will be collected which can be coded. From these codes, memos describing theoretical concepts can be written, which when elaborated allow for the theoretical sampling of individuals and groups to the research. Theoretical sampling is far more difficult than collecting data with pre-planned groups; individuals and groups selected theoretically require that decisions are made informed by thought, analysis, and search. The sample’s ongoing inclusion in the study is for a strategic reason, to test emerging theory. Here again Glaser and Strauss differentiate themselves from their nemesis, the verifier of theory. Evidence, they suggest, is not collected because it will accurately describe or verify some preconceived theoretical position, nor is the researcher selecting groups because they show difference in a particular variable. The logic is not one of: ‘I plan to sample this group because they use this service, and this group because they do not use this service’. These rules of evidence hinder the discovery of theory. Groups are chosen because the data they produce relates to a particular category in the research. The search is for groups that display the category under investigation in different situations. Thus, in their study of the Awareness of Dying, Glaser and Strauss (1965) observe the interaction between nurses and their patients in hospitals, the home, nursing homes, ambulances, and even in the street following trauma, and through these the various interactions between nurses and dying patients. Such diversity of investigation allows for observation of the similar and diverse properties of categories.

Strategies of constant comparison and their purpose

There are a further three considerations in the choice of which group to sample next. First, the scale of generality the researchers wish to achieve with their theory. What is the scope of the theory? Does it relate to a particular setting, or is the research making claims for other settings too? If Glaser and Strauss’s 1965 study Awareness of Dying discussed in the last section had just been conducted in a hospital, then the theory would have been confined to hospitals alone. The scope of the theory would have been limited by these choices.

The second sampling choice is whether to minimise or maximise similarities in data categories. These conceptual categories discovered in the early research are transformed into hypotheses to be tested with similar and diverse groups. The purpose of this strategy in the research is threefold. It ‘forces’, to use Glaser and Strauss’s term, the researcher to generate categories, their properties, and interrelations in their emergent theory. Similar data collected in similar groups verifies the usefulness of the categories, aids in the generation of basic properties, and establishes the conditions in which the emergent theory will apply. Understanding these conditions of context allows the researcher to make predictions about the generality of the theory to other settings. These claims can be made stronger and the emergent theory refined through the strategic sampling of similar data categories between maximally varied groups. The emergent theory’s scope is extended.

An overarching logic of grounded theory as described by Glaser and Strauss (1967) is the linearity of its implementation. This is the reason for numbering the stages in Table 1.1. Iteration between the joint collection, coding, and analysis of data happens within each stage. Nonetheless, while they accept some overlapping of the stages, the rigour of the discovery of emergent theory rests on theoretical sampling proceeding from stage to stage. The basic work of establishing concepts, properties, and categories through minimising the difference between the groups sampled in the research precedes strategies of maximisation. The early work of openness and categorisation are the precursors to emergent theory. Maximum variation is sampled to bring out:

the widest possible coverage of ranges, continua, consequences, probabilities of relationships, process, structural mechanisms … all necessary for elaboration of theory. (Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 57)

However, such a wealth of insight requires these methodologists to accept that they might have to revisit their early data collection, as their understandings of phenomena change. So, for instance, Glaser and Strauss (1967) note how through observing the ways in which Malayan families care for their dying relatives in Malaysia, they were obliged to go back to their own data on US families. Their conceptual framework had characterised US families as ignoring their dying relatives who they regarded as a nuisance. But a re-examination of the data led them to identify ‘not-so-observable’ phenomena in their data, leading them to discover several different ways in which US families care for their dying relatives.

The purpose of constant comparison is to extend empirical theory into the realm of formal theory. This theoretical sampling can only be done, according to Glaser (1978), when the emergent and empirically generated theory has been stabilised. Then, at last, the researchers can make their weary way to the library in search of other studies and other theoretical accounts or sample dissimilar and non-comparable groups. These comparisons provide the researcher with further instances to facilitate explanation at the higher conceptual level of formal theory and extend the scope of the findings from the research.

Grounded theory in action in a study of the awareness of dying

An important influence in the development of grounded theory was the study Awareness of Dying conducted by Glaser and Strauss (1965), in which they note that they have written theory on almost every page. Our interest here is not the theories discovered, however fascinating, but the methods used to arrive at these theories, and in particular the decisions made about who and what to sample in the research. In an appendix Glaser and Strauss (1965) discuss their methods of data collection and analysis. The first notable feature, which appears to sit at odds with the position taken in The Discovery of Grounded Theory, is the amount of work that was done before entering the field. They discuss a preliminary stage in their data collection, which ‘governed further collection and analysis of data’ (1965: 286). In this section, they discuss how their understanding of their research interest, an awareness context of death and dying, was ‘foreshadowed’ by personal circumstances and experiences. These authors describe how these circumstances and experiences informed theory development in the early research. First, a state described as ‘closed awareness’ and then a ‘mutual pretence awareness’ experienced by Strauss during the death of his mother. A while later he was involved in ‘an “elaborate collusive game” designed to keep a friend unaware of his impending death (closed awareness)’, (Glaser and Strauss, 1965: 287). Glaser, too, had...