![]()

1

What is self-esteem?

CLARIFYING THE TERMINOLOGY

The development of the positive qualities of personal integrity, self-acceptance, respect for the needs of others, and the ability to empathize would comprise the ideal self in a civilized society. It is the development of these ideals that are the goals of a self-esteem enhancement programme as defined in this book. In order to achieve these goals it is important first to clarify the terms used in self-esteem enhancement. We all have our own idea of what we mean by self-esteem, but in any discussion of self-esteem amongst a group of teachers there are likely to be several different definitions. The chances are that amongst these definitions the words self-concept, ideal self and self-image will appear.

The fact is that the literature until fairly recently has tended to use many terms like these to mean the same thing. It is no wonder teachers therefore have been confused and as a result have tended to dismiss the concept as yet another of those ambiguous terms so often found in discussions of education. Fortunately, the concept has gradually been more clearly defined thanks to the work of people like Argyle in Britain and Rogers in the USA.

SELF-CONCEPT

The term self-concept is best defined as the sum total of an individual’s mental and physical characteristics and his/her evaluation of them. As such it has three aspects: the cognitive (thinking); the affective (feeling); and the behavioural (action). In practice, and from the teacher’s point of view, it is useful to consider this self-concept as developing in three areas – self-image, ideal self and self-esteem. Self-esteem, of course, is the focus of this book. To understand the concept of self-esteem, however, it is necessary to define self-image and ideal self.

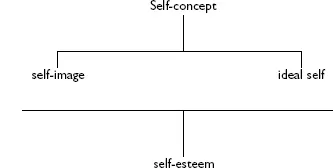

Self-concept is the umbrella term under which the other three develop. The self-concept is the individual’s awareness of his/her own self. It is an awareness of one’s own identity. The complexity of the nature of the ‘self’ has occupied the thinking of philosophers for centuries and was not considered to be a proper topic for psychology until James (1890) resurrected the concept from the realms of philosophy. As with the philosophers of his day, James wrestled with the objective and subjective nature of the ‘self – and ‘me’ and the ‘I’ – and eventually concluded that it was perfectly reasonable for the psychologist to study the ‘self’ as an objective phenomenon. He envisaged the infant developing from ‘one big blooming buzzing confusion’ to the eventual adult state of self-consciousness. The process of development throughout life can be considered, therefore, as a process of becoming more and more aware of one’s own characteristics and consequent feelings about them. We see the self-concept as an umbrella term (see Figure 1.1) because subsumed beneath the ‘self’ there are three aspects: self-image (what the person is); ideal self (what the person would like to be); and self-esteem (what the person feels about the discrepancy between what he/she is and what he/she would like to be).

To understand the umbrella nature of the term readers might like to ask themselves the question, ‘Who am I?’, several times. When first asked, the answer is likely to be name and perhaps sex. When asked a second time the person’s job or occupation may be given. The self-image is being revealed so far. Further questioning will lead to the need to reveal more of the person and, in so doing, the ideal self and the self-esteem. For example, ‘I am a confident person’ (self-esteem); ‘l would like to be able to play cricket’ (ideal self).

Each of the three aspects of self-concept will be considered in turn. Underpinning this theoretical account of the development of self-concept will be the notion that it is the child’s interpretation of the life experience which determines self-esteem levels. This is known as the phenomenological approach and owes its origin mainly to the work of Rogers (1951). It attempts to understand a person through empathy with that person and is based on the premise that it is not the events which determine emotions but rather the person’s interpretation of the events. To be able to understand the other person requires, therefore, an ability to empathize.

Figure 1.1 Self-concept as an umbrella term

SELF-IMAGE

Self-image is the individual’s awareness of his/her mental and physical characteristics. It begins in the family with parents giving the child an image of him/herself of being loved or not loved, of being clever or stupid, and so forth, by their non-verbal as well as verbal communication. This process becomes less passive as the child him/herself begins to initiate further personal characteristics. The advent of school brings other experiences for the first time and soon the child is learning that he/she is popular or not popular with other children. He/she learns that school work is easily accomplished or otherwise. A host of mental and physical characteristics are learned according to how rich and varied school life becomes. In fact one could say that the more experiences one has, the richer is the self-image.

The earliest impressions of self-image are mainly concepts of body-image. The child soon learns that he/she is separate from the surrounding environment. This is sometimes seen amusingly in the young baby who bites its foot only to discover through pain that the foot belongs to itself. Development throughout infancy is largely a process of this further awareness of body as the senses develop. The image becomes more precise and accurate with increasing maturity so that by adolescence the individual is normally fully aware not only of body shape and size, but also of his/her attractiveness in relation to peers.

Sex-role identity also begins at an early age, probably at birth, as parents and others begin their stereotyping and classifying of the child into one sex or the other. With cognitive development more refined physical and mental skills become possible, including reading and sporting pursuits. These are usually predominant in most schools so that the child soon forms an awareness of his/her capabilities in these areas.

This process of development of the self-image has been referred to as the ‘looking-glass theory of self’ (Cooley, 1902) as most certainly the individual is forming his/her self-image as he/she receives feedback from others. However, the process is not wholly a matter of ‘bouncing off the environment’ but also one of ‘reflecting on the environment’ as cognitive abilities make it possible for individuals to reflect on their experiences and interpret them.

Self-image is our starting point for an understanding of self-esteem.

IDEAL SELF

Side by side with the development of self-image the child is learning that there are ideal characteristics he/she should possess – that there are ideal standards of behaviour and particular skills which are valued. For example, adults place value on being clean and tidy, and ‘being clever’ is important. As with self-image, the process begins in the family and continues on entry to school. Once they attend school they would normally learn that teachers also value the kind of behaviour valued by their parents. Not only are they praised for behaving appropriately, but they also receive rewards and positive feedback from their teachers when they learn to read and to write. In this way, praise becomes a goal and provides them with motivation for further appropriate behaviour and achievements.

Further development of the ideal self occurs as children come into contact with the standards and values of people outside the family and the school. The child is becoming aware of the mores of the society. Body-image, again, is one of the earliest impressions of the ideal self as parents comment on the shape and size of their child. Soon the child is comparing him/herself with others and eventually with peers. Peer comparisons are particularly powerful at adolescence. The influence of the media also becomes a significant factor at this time with various advertising and showbusiness personalities providing models of aspiration. Role models in the media often have a powerful influence although it is usually the people closest to them that continue to have the strongest influence. However, it is the positive qualities of empathy and respect for others, and a sense of personal responsibility that ought to be the ideal goals of people in a civilized society. So the ideal self does not merely comprise the values and standards of the person’s immediate social group but, rather, the ideals and standards of a larger civilized society.

With maturity a person’s total experiences are able to be evaluated more realistically, although it is doubtful whether a person ever becomes sufficiently mature to be completely uninfluenced. Our early experiences may continue to influence our present behaviour to some extent although we all have the potential for becoming self-determinate. The schoolchild is most likely to be at the stages of accepting these ideal images from the significant people around him/her and of striving to a greater or lesser degree to attain them.

SELF-ESTEEM

Self-esteem is the individual’s evaluation of the discrepancy between self-image and ideal self. From the discussion on the development of self-image and ideal self it can be appreciated that the discrepancy between the two is inevitable and so can be regarded as a normal phenomenon.

Self-esteem can be either global or specific and there is a relationship between these two facets of self-esteem. Global self-esteem refers to an all-round feeling of self-worth and confidence. Specific self-esteem refers to a feeling of self-worth and confidence with regard to a specific activity or behaviour.

If a particular activity or behaviour is valued, the chances are that eventually it will affect a person’s global self-esteem. For instance, a child may have an overall feeling of positive self-worth, that is, high global self-esteem, but feel inadequate when having to play sport. If sport is highly valued in this school, their global self-esteem will be threatened. However, if sport is not valued in their school, their global self-esteem may remain unaffected. Even if a regular activity such as sport is valued and the child fails at this, it should still be possible to maintain high self-esteem by avoiding sport. This strategy of avoiding specific activities is more easily accomplished in adult life than in the school situation. It is difficult to avoid school activities, especially when they are so often compulsory. An example of such an activity would be learning to read.

In the process of normal development there is always a discrepancy between self-image and ideal self. It is this discrepancy that motivates people to change or to develop social, physical and academic skills. However, in some cases, adults might be anxious about their child’s slow progress. They may communicate their disapproval of the fact that the child has not yet reached their ideal. Sadly, the child usually interprets this criticism as not just disapproval over their failure in the activity concerned but disapproval of them as a person. Consequently, these children also become extremely anxious about their failure to meet the adult’s standards and, so, their global self-esteem drops.

Indeed, there is evidence from clinical work that without this discrepancy – without levels of aspiration – individuals can become apathetic and poorly adjusted. Just as in physiology the nerve impulse is always active so, it seems, the psyche also needs to be active. It is a mistake to think that the ideal state is one of total relaxation. Whilst this may be desirable for a short while, in the long run it can produce neurotic behaviour. For the person to be striving is therefore a normal state.

What is not normal is that the individual should worry and become distressed over the discrepancy. Clearly, this is going to depend in early childhood on how the significant people in the child’s life react to him/her. For instance, if the parent is overanxious about the child’s development this will soon be communicated and the child, too, will also become overanxious about it. He/she begins first by trying to fulfil the parental expectations, but if he/she is not able to meet them begins to feel guilty.

It is interesting that the young child is so trusting in the adults that he/she does not consider that they could be wrong or misguided. When a child fails to live up to parental expectations he/she blames him/herself at first, feeling unworthy of their love. Moreover, this failure in a particular area generalizes so that he/she would not just feel a failure, say, in reading attainment, but will feel a failure as a person generally. The child is not able to compartmentalize his/her life as can the adult. If we adults cannot play chess, for instance, we avoid the chess club. If the child fails in, say, reading, he/she cannot avoid the situation.

Indeed, th...