![]()

| 1 | Resemblance, representation and reality |

Communication is central to how we get along in the world: how we make meanings, and how we both make sense of, and organize, our environments. It includes not only spoken and written language, but also visual imagery, bodily gestures, music, architectural design, and all the many other ways by which we insert ourselves into, and communicate with, the world. Representation is the dominant system by which we handle communication, but it is not the only option. In fact, it is a comparatively new system for meaning-making: a number of other conceptual frameworks and systems served for many centuries and, in some cases, continue to serve.

It is only in the past few hundred years – the modern era, the period from about the seventeenth century on – that representation, strictly speaking, has dominated approaches to the use of language and the construction of meaning. As Christopher Prendergast writes:

as a concept supplying a regulatory matrix of thought, representation, notwithstanding its ancient lineage, is an essentially modern invention, one of the master concepts of modernity underpinning the emergence of what Heidegger called the Age of the World Picture, based on the epistemological subject/object split of the scientific outlook: the knowing subject who observes (‘enframes’ is Heidegger’s term) the world-out-there in order to make it over into an object of representation. (2000: 2)

Of course there have always been gestures towards what we now understand as representation: ways of separating ourselves from the objects and ideas under discussion, systems of delegation, and substitutions. The idols that stand in for gods in ancient cultures are substitionary, and so are representational. But how people have understood themselves in relation to both the world and the systems of communication has changed radically over the centuries. An earlier model, and one that continues to inflect our perception of and organizing of the world, is resemblance.

BEFORE REPRESENTATION

Stuart Hall describes as ‘the reflective’ approach to language (1997a: 15) the notion that a sign reflects an already-existing meaning or identity. This approach was written about in very ancient texts – those of the Greek philosophers, for instance, where it is named mimesis, or resemblance, or similitude. The idea is that the sign actually resembles, and does not simply signify, the thing itself. Although like representation-proper it stands in for the original thing, it does so in a direct relationship based on imitation, or likeness.

Mimesis, or resemblance, can be found in virtually all human mark-making or other cultural practices. A portrait that looks like its subject; music that sounds like the wind rustling the leaves of a tree; clothes that resemble the feathers of a bright bird; a garden designed to look like a forest – all these are mimetic signs. It can also be a mode of writing, especially in pictographic forms like Egyptian hieroglyphics or Mandarin characters. Here the writing is a series of marks that act as signs because they stand in for the topic under discussion (they ‘represent’ that topic). But unlike symbolic representation, they communicate by looking like the things to which they refer. The written sign for water, for instance, might be a series of wave-like lines. The written sign for a god might look like statues of that god; and the statues themselves might have elements that resemble the qualities attributed to that god: perhaps huge muscles for power, a lion’s head for nobility, a snake’s body for speed, and so on.

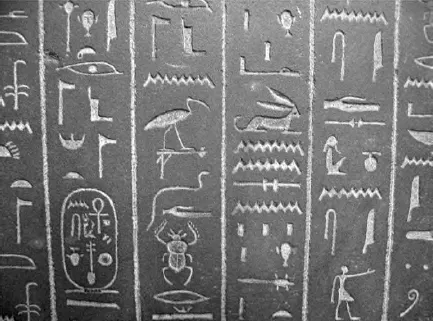

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs are perhaps the best-known of written texts based on resemblance; they use many pictographic elements, along with abstract signs, to tell complex stories, relate dense histories, and to record bureaucratic matters such as policies or budgets. The more famous objects are sarcophagi, and thanks to the efforts of Egyptologists there are many examples of tombs and other iconography and objects of the dead in museums around the world.

The image here (from an exhibition at the British Museum) is inscribed on the tomb of a royal woman from Thebes, who died about 530BCE. I cannot read the hieroglyphs, but I assume – based on other sarcophagi – that the story told on the whole object, of which this is a tiny extract, describes her life and times, and comments on her death. There are recognizable images: an ibis, a scarab, an eye and a person extending an arm; there are other more abstracted icons, such as the jagged and curved lines and other marks that bear no obvious resemblance to anything. I can recognize, or think I recognize, elements in the text; but I can only guess at the meaning of the signs and the text as a whole, based on what I think the inscriptions resemble, and what little I know about ancient Egyptian culture.

Figure 1.1 Inscription on an Egyptian tomb, British Museum (photo dated 2006)

SIMULACRUM AS RESEMBLANCE

In fact, pictographic or iconographic writing was not really a simple or direct system of resemblance: the hieroglyphs resemble the objects only in a limited, abstract way, and are transparent only to those trained in their conventions. Only the resemblance that is called a simulacrum can really invoke the original by perfecting duplicating it. For an example of what simulacrum is and how it works, let’s discuss the Alfred Hitchcock movie Vertigo (1958). The movie opens with the protagonist, Scottie (James Stewart), unable to save a police officer from falling to his death from the roof of a tall building. This trauma causes him to suffer (the eponymous) vertigo, and is the core of the plot that follows. Scottie falls in love with Madeleine (Kim Novak), the wife of an important local man; but she is a troubled woman, obsessed with death, and apparently commits suicide. Scottie, desperate with grief and loss, finds a possible substitute for her in Judy. But where Madeleine is elegant and sophisticated, Judy is a loud shop girl. To make her the perfect copy, Scottie goes to considerable effort to remould her and form her into ‘Madeleine’. She is not to be a substitute or resemblance, but a simulacrum: a perfect stand-in for the original, virtually indistinguishable from the source. Of course it doesn’t work; but it is an interesting experiment in resemblance, simulacrum and the idea of presence – whether a sign can really make the original, real-world object present again.

The reason that no simulacrum can in fact perfectly stand in for the original is because there must always be a gap between the sign and what it signifies. Plato discussed this two millennia ago, in his argument that all we see and do is but a pale imitation of the ideal Form for the things we see and do, that exists in some transcendental realm, and is the origin for everything in our world of simulcra. Our efforts to produce representations or resemblances of that Form will only be partial and equivocal; and will be based on our prior understandings of what is important, of what something means, and of the right way of showing it. Scottie’s attempt to reproduce Madeleine through a representation – Judy-the-simulacrum – failed not only because the Madeleine/Judy distinction was a trick, not only because there must be a gap between the sign and what it points to, but also because he did not really believe in the value of the outcomes.

ANALOGY AND SENSE

Even a perfect resemblance will be perfect only because it fits with ideas we might have about perfection, and about the thing it resembles. What is important here is that all uses of representation to make meaning are fundamentally epistemological. That is, they are not just about communicating something, but are based on theories of knowledge. There is no simple mirror of the world, but only ways of seeing that are inflected by philosophical and hence ideological perspectives. Slavoj Zizek argues that ideology is a ‘generative matrix that regulates the relationship between visible and non-visible, between imaginable and non-imaginable’ (1994: 1). We can only see, or make sense of what we see, on the basis of how we understand the world to be.

The world in medieval Europe was viewed through the epistemological filter of Christianity, so that it and all its contents were perceived as being there for a divine purpose (Eco 1986a: 53). Virtually everything one could see had a meaning based on some sort of resemblance to, or echo of, or analogy of, the divine: white meant light and goodness while black symbolized evil; lambs reminded viewers of Christ; doves were echoes of the holy spirit; olive branches indicated peace, and so on. Nor were Christians the only ones to make use of allegory. It was widely used in the ancient world: the image opppsite, for instance (Figure 1.2), is part of a fresco in Pompeii that is rich in elements that point to something beyond the everyday. Something similar still occurs, though more often in fun. Halloween imagery is an example of a cultural form that recalls the traditional logic of analogy: a pumpkin carved into a frightening mask, for instance, resembles an idea of the devil, and works best at night – the time of darkness and hence evil. The one in Figure 1.3 is carved and lit so that it does something unexpected: the apparent image of pretty stars actually throws a demonic face against the wall.

Figure 1.2 © Paul Travers 2006

Figure 1.3 © Paul Travers 2006

As we saw in the case of hieroglyphics, the resemblance between the sign and the referent might be very slight, no more than an echo. But that was enough for the era, where what was required for meaning was not a sort of photographic reproduction, but a ‘witty coincidence’: just enough hints for someone to make a connection between the concrete and the abstract – the thing observed and the concept for which it stood. Resemblance, especially in the form of analogy (a lamb stands for Christ, for instance), was a way of filling the gap between the concrete and the abstract. There was never only one way of making analogies to fill that gap, though. Barbara Stafford writes that resemblance is an attempt to find sameness in difference (1999: 2): to see how a wavy line might be the same as a body of water, to see how a dove might be the same as God. It does recognize that things cannot precisely and perfectly represent other things, but suggests that there are ways of finding points of connection and association that help us to make sense of the world.

To do so we have to ignore the real differences, and look only for the possibility of sameness. For example, philosopher Adam Dickerson discusses how we read a smiley-face emoticon. The ‘face’ is on the one hand simply a combination of lines and dots, and on the other hand is itself and itself only. It is neither a resemblance nor a representation, because there is no actual smiley-face outside the picture that it might look like, or for which it is a substitute. Yet we can read it as both resemblance and representation. No one looks like a smiley-face; but the big smile on the emoticon sort of resembles a happy person. There is nothing outside the picture that is an original smiley-face which the emoticon can render in an image to make it present again, but there are happy people, and it stands for us as a valid representation (Dickerson 2004: 15). We know it is neither a face or a smiling face, simply a pattern of lines. We know it is not in the picture either – it is the picture; and yet we comfortably say that it is a face, smiling, in the picture; and it is a picture of smile. It is nonsense, and yet it makes perfectly good sense. And it spirals on to make sense of other nonsense objects. This manhole cover (Figure 1.4), for instance, looks like someone winking, someone almost but not quite smiling, someone who is present. And yet all it is, is a chunk of metal on a Paris street, covered in litter.

The smiley-face is similar in its properties to pictographic writing: it gives a direct reflection of things that are in the world. But the signs Eco identifies as medieval representations of God rely on a different logic of resemblance. Here the resemblance is not a sort of mirror image, but a resemblance of affinity, or sympathy – based on connection and not of reflection. We find this in images and also in spoken or written language. Philosopher John Searle, for instance, points out that if you say someone is tall, he or she is tall only as an attribution, not a reality (1993: 86–7). Every person, after all, is short in real or actual terms, when say, compared with a giraffe – even a giraffe who is short in giraffe terms. But a person short in actual terms may well be tall in relational terms: a women who measures two meters – short in comparison with giraffes – is tall by human standards: a women who measures only 2.5 meters is tall in relation to toddlers.

Figure 1.4 A manhole cover, Paris (2006)

ANALOGY AND EDUCATION

This is a mode of language use that is more closely associated with affect – feelings, attitudes – than with deductive reason. It is figurative rather than factual, and more inclined to communicate through story than through evidence and argument. It is thus a system of communication that is very well-suited to teaching. In the Medieval period the focus on seeing everything as an analogy for the divine served as a reminder to people about the centrality of their religion to their lives. In a similar way, experts often use analogy – resemblance – to explain complex issues to those who do not know their field of expertise.

Writings by early medical scientists are full of analogical explanations and descriptions of the human body and how it works. The pelvic cavity was often described as a cave, and this allowed listeners – students, other doctors – to visualize its form and to be alert to important issues for research or examination (it is dark in there; there may be unexpected tunnels or fissures; go carefully!). Following the same principle of rendering visible something that is hidden and complex, people using language to persuade will often use analogy. For example, environmentalists will talk of the ‘rape’ of the earth, an analogy that brings to mind vulnerable femininity, brute force, violation, and the need for people of goodwill and legal integrity to intervene. These are not ‘true’ images in the sense used by deductive reasoning, and nor are they ‘true’ – mirror image – resemblances, but they are pointers to something that a speaker might wish to posit as true.

IDEOLOGY AND RESEMBLANCE

It is important to remember that all resemblances, and indeed all representations, are only partial and contingent. We interpret signs in order to extract a desired truth. In Victorian England there was a tradition of using an extensive range of images (signs) on gravestones to tell something important about their beliefs. A number of graves in London’s Highgate Cemetery, for example, are adorned with carvings of guttering candles. This is a sign that reminds viewers of the transitory nature of life. There is no reason it should necessarily do so; after all, a candle, however low it has burned, looks nothing like a dying person. The only likeness is one of connection – both are dying. And even in what might seem to be the most naturalistic, the most mimetic, form of communication, that of onomatapoeia, cultural differences far override whatever might be the actuality of the referent. In France, for instance, barking dogs make a sound rendered as ouaoua; in Anglophone societies the same sound is rendered ‘woof’, or ‘yap’ (Belsey 1980: 41). The French and the English both, I assume, hear their dogs as ‘naturally’ making those very different sounds – even hear the same dog making thos...