![]()

PART I

PRINCIPLES AND METHODS

![]()

1 | Psychoneurology: The Program |

| | Rom Harré and Fathali M. Moghaddam |

‘There is nothing in the universe except meanings and molecules.’ (Anon)

As a science emerges from a common-sense understanding of certain kinds of phenomena it only gradually becomes clear what are the fundamental entities of the ‘world’ under study. Psychology grew out of our everyday reflections on the beliefs and practices relevant to people thinking, acting, feeling and perceiving. The scientific study of these phenomena should, we believe, be built on a common fundamental presumption: that persons are the basic beings at the root of a scientific psychology. It is persons who think, act, feel and perceive. Persons are the fundamental entities of psychology.

In a sense a person has no parts, in particular, a person is not a union of a mind and a body. However, while persons have no parts, each person, though a singularity, has a vast array of attributes. Some are material attributes and some are mental capacities, powers and dispositions. Though people are sometimes acted on by outside forces they always retain their status as ultimate agents, at least in principle. Personal agency, we might say, is the default position when we are studying what people do. When people lose their powers to think, act, feel and perceive the world around them and the condition of their own bodies, we take them to be in need of care and perhaps of cure. For example, in the law courts we consider the accused responsible for his or her actions, unless there is a successful plea of insanity.

For more than four centuries psychology was led away from the most fruitful research domain by the widespread assumption that we should treat the material attributes of persons as properties of the human body, a material substance, and the mental attributes of persons as properties of a parallel stuff, the human mind. Persons were taken to be ‘miraculous’ conglomerates of bodies and minds, a material thing somehow joined to an immaterial thing. In the 20th century this duality assumption subtly influenced the thinking of the majority of psychologists. Even those who rejected the idea of the mental aspects of a human being as attributes of a substantival mind, nevertheless still implicitly subscribed to the distinction between mind and body even and especially when they declared that the way human beings think, act, feel and perceive can be understood in material terms. We believe that the next step in the development of psychology, as a human science for the third millennium, will be achieved when the very distinction between minds and bodies is abandoned.

In this book we set out the various ways a hybrid conception of persons as meaning-making embodied agents depending on one another for their very existence as persons can advance the project of a scientific psychology. We will demonstrate the power of this proposal across the traditional domains of psychology, thinking, acting, feeling and perceiving to invigorate the traditional divisions of psychology as a human science.

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (1832–1920) was born in the town of Neckarau in Germany, the son of a Lutheran minister. After boarding school he went on to university to study medicine. According to the German custom he attended lectures at several universities, including Tubingen, Heidelberg and Berlin.

In 1857, he began to teach physiology at the University of Heidelberg. From 1858 to 1864 he was assistant to the Heinrich von Helmholtz, the great German polymath.

In 1864, he moved to Leipzig where he began experimental studies of the senses, particularly vision. By 1881 he had gained sufficient confidence to begin teaching a class on physiological psychology, essentially concerned with the correlations between various physiological phenomena and individual experiences of sight, sound and so on. In 1879, Wundt claimed that he had founded an independent science of psychology. The fame of his laboratory soon spread, attracting students from across the world, including E. B. Titchener and G. Stanley Hall.

According to Wundt, psychology was the study of conscious experience. A person was surely the best observer of his or her own experience, so introspection became the major experimental method, as a rigorous and highly disciplined research method, by which elementary sensations were extracted from the complexities of actual experience without imposing interpretations. Together with the intensity and duration of sensations went attention to the qualities of the feelings that accompanied them. The combination of sensations and feelings is what constitutes our mental functioning.

Later in life Wundt began a very different kind of psychology – Volkerpsychologie – something very like the cultural psychology we recognize today. Wundt set out to show by the accumulation of examples of cultural phenomena of all kinds, that key aspects of human life could not be accounted for by the attention to individual consciousnesses. They were distinctive in kind and origin, requiring the hypothesis of collective mental processes. Wundt never quite arrived at the current idea of how such processes are possible through the use of language and other symbolic systems to generate interpersonal psychological processes. He died in 1920.

This project is not new. In the 19th century Wilhelm Wundt directed a program of experimental researches to the study of the correlations between the elements of conscious experience and the physical stimuli which brought them about. However, he also undertook a vast study of the cultural side of human psychology and published an enormous 10-volume treatise on Volkerpsychologie, commonly translated as ‘folk psychology’ (Wundt, 1916). Here Wundt’s focus was on the form that human activities take by adherence to norms rather than by responding to events or states as causes.

Another version of a two-pronged psychology was proposed by William Stern at the beginning of the 20th century. Philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953) and psychologists such as Lev Vygotsky (1978a) and Jerome Bruner (1986) anticipated the idea of such a hybrid. It is being rediscovered in the 21st century. Stern coined the phrase ‘unitas multiplex’ to capture the idea that though persons are the fundamental unanalyzable units of the science of psychology each has a complex and unique manifold of attributes (Stern, 1938). Psychology must somehow blend our knowledge of meanings and our knowledge of molecules. While seeking universal features of the human form of life, psychology must acknowledge the individuality of each human being. During the latter part of the 20th century there emerged a robust literature representing psychology as a normative science, for example, as reflected by developments in cultural psychology (Cole, 1996), socio-cultural psychology (Valsiner & Rosa, 2007), as well as various other emerging normative research traditions (Moghaddam, 2002, 2005, ch. 20).

William Stern (1871–1936) was born in Berlin into a middle-class family, the only child. His father had a modest business designing wall paper. After high school he entered the University of Berlin in 1888 to study philology but soon changed to philosophy and psychology. He realized that psychology could not be fruitfully developed according to the methodology of the natural sciences as presented by the positivists. In 1899, he married Carla Joseephy with whom he began their famous diary recording the development of their three children. After his doctoral studies in Berlin he moved to the University of Breslau in 1897 to work under Herman Ebbinghaus, staying until 1916. Though he invented the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) as a ratio of mental to chronological age he soon became sceptical of the uses to which it had been put.

His importance to the advent of hybrid psychology was his emphasis on the distinction between things and persons, and his realization that persons were to be understood as individuals. He came to this insight from his work on differential psychology. It is not a great step to realizing that acknowledging the importance of differences between people implies that each person is in many respects unlike any other. His conception of critical personalism came from the further insight that people are active agents capable of evaluating a huge variety of thoughts and actions. The person is a simple entity with complex attributes. For this he coined the phrase ‘unitas multiplex’.

In 1916, he moved to Hamburg where he helped to found the university in 1919. He continued in Hamburg until the Nazi regime banned anyone of Jewish origins from university teaching. In 1934 he moved to Duke University in the United States. He died in Durham, NC, on 27 March, 1938.

Under the principle of unitas multiplex our research will involve the study of ‘bodily’ aspects such as the running of molecular machines and ‘mental’ aspects such as the unfolding of sequences of meanings within the constraints of the norms of our local ways of life. The results of the study of each such aspect will reveal the tools and instruments with which people manage their lives.

Scientific Methodology and the Two Concepts of Causality

In order to understand the way a scientific psychology should develop we need to understand the basic principles of scientific research thoroughly. Unfortunately, through a series of misunderstandings, a good deal of the psychological research of the last half century has been profitless, based on a flawed philosophical account of the nature of scientific explanations.

Human beings long ago became aware of the world around them and of their own lives as a flux of change. Though most change is smooth and continuous the human way has been to chop up the flow into sequences of events, happenings. The first step in a scientific research program is to develop a classification system for the happenings that are the focus of research. Sometimes events seem to defy all pattern and order, but more often regular sequences are discernible among types of happenings. We observe and catalogue sequences of changes, both continuous and discrete.

How can regularities in the flux of events be explained? Pairs of sequential events are picked out in terms of the concepts of ‘cause’ and ‘effect’. To bring about a desired state of affairs one makes the cause happen, and then, all else being equal, we can expect that the desired effect will occur. We boil the oatmeal and the porridge thickens. But what mediates the transition from cause event or state to effect event or state, from the raw to the cooked? As a general rule when we first notice a regularity among pairs of events or states we have no idea what the intervening process might be. We soon turn to speculations about unobservable processes that link cause events and states with their effects. Alternatively, we ascribe some sort of efficacy, power or agency to something that seems to be the efficacious cause. Already we have the source of a long-running duality in how people understand causality.

Agency explanations abounded in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in physics and chemistry. They were matched by an equal abundance of hidden mechanism explanations. While Isaac Newton filled the universe with forces and powers, Robert Boyle filled it with invisible corpuscles or molecules. Though we can observe the effects of the action of forces, the forces themselves remain hidden. The same is true of the consequences of rearrangements of the minute parts of material things. We can observe the outcome of a chemical reaction but we cannot observe the interchanges of atoms among the invisible intangible molecules.

However, if we think that knowledge must be certified by observation then speculations about forces and powers as well as hypotheses about invisible atoms ought not to be included in the realm of scientific certitude. In an influential study published in 1787(1962), David Hume argued that the only legitimate meaning that could be given to the concept of causation among events and states must be limited to the fact of regular sequences in like pairs of events. Any idea of efficacy or power to bring about changes must be put down to the psychological effects of observing many such regularities. Our sense of the necessity of a causal process is nothing more than a tendency or habit to expect an event of the effect type when we have observed one of the cause type. No connection can be observed between them. To establish the existence of a causal sequence all we can do is to turn to statistical analyses of lots of similar cases. The danger of crossing the boundary between certitude and speculation precludes our seeking the active powers or the hidden mechanisms that bring about the effects in which we are interested. In the 20th century this point of view was revived in the influential writings of the positivists (see Ayer, 1978), the philosophers of the Vienna Circle. Intent on ridding the world of ungrounded metaphysical speculations and of the other-worldly fantasies of religion, they managed to eliminate most of science as well. The effect of these ideas diffusing into psychology was disastrous. Unfortunately, under the influence of James B. Watson and the behaviorists, psychologists abandoned agent-causality completely and took up the Humean or positivist version of event-causality, without the underpinning of hypothetical causal mechanisms. In the intervening years various attempts to make up this deficit have been proposed, such as the computational model of cognition. From our point of view agent-causality is the appropriate concept for cultural/discursive studies of human thinking and acting, while a kind of event-causality that is based on hypothetical generative mechanisms is the appropriate concept for neuroscience and related programs.

There is no place for the Humean regularity of sequence concept in any science. This point of view became a kind of dogma despite the fact that the sciences had advanced by the very route that Hume would have forbidden them, by developing hypotheses about the causal powers of natural agents such as magnetic poles and electric charges and about the hidden mechanisms that brought about orderly change in the world. The mechanism of the solar system explained eclipses, the seasons, the phases of the moon and so on. This mechanism was held together by the force of universal gravity and the kinetic energy and momentum of the moving planets. What was there not to like in this magnificent Newtonian analysis of the solar system?

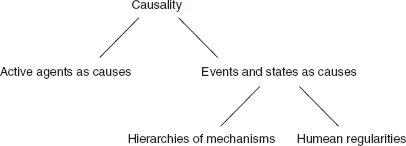

Drawing on the triumphant success of the natural sciences we have two kinds of causality available for the psychology of the third millennium, each with its proper domain of application and each with its attendant implications. Agent-causality focuses on beings with powers to act, which are shaped and constrained by all sorts of environmental conditions. Event-causality focuses on hierarchies of hidden mechanisms which underpin the patterns of meaningful actions agents bring about. How to link these two causal modes into a coherent non-reductive hybrid is an important part of the approach to psychology we take in this book.

Cultural psychology is the study of active people carrying out their projects according to the rules and conventions of their social and material environments. Thus it is normative. It conforms to the principle of agent-causality.

Neuroscience is the study of the mechanisms which active people use to carry out their projects and plans. It conforms to the principles of hierarchical event-causality. Neuroscience does not reach to the depths of the physical processes on which neuro-events ultimately depend, and where agent-causality re-emerges among the basic electromagnetic groundings of the universe.

We can see the pattern of explanation formats in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Varities of causality

When we are dealing with cognitive phenomena, with social actions and relations, with emotional states and displays, with motives and with problem-solving abilities and much more, the causal mode we need is agent-causality. When we are dealing with the activities of the brain and nervous system the causal mode we need is hierarchies of mechanisms. If we want to create a science of the powers of human thought, feeling, action and perceptions, we never need Humean regularities except as the starting point for beginning a search for genuine causal explanations.

At present, and for the foreseeable future, both neuroscience and normative or cultural/discursive psychology are developing vigorously. In this text we will show ways in which various links can be established whereby the integrity of each paradigm is maintained, and how they can inspire each other.

Despite the rapid developments in normative psychology, the mainstream ‘introduction to psychology’ texts remain true to an event-causality model appropriate to neuroscience but wholly inappropriate to studies in the meaning-dominated realm of human thought and actions, and completely neglect the ‘second psychology’ based on persons as agents. Traditional Humean event-causality psychology is well represented by Kalat’s hi...