![]()

1. Children as reflective learners

Emma McVittie

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- distinguish between being a reflective practitioner and how to encourage children to reflect;

- identify how reflection supports creative approaches to learning in the classroom;

- analyse what a reflective classroom looks like in practice.

What is reflection from a practitioner’s perspective?

Theories about reflection tend to be fluid and not fact; they are amended and interpreted according to the needs of the researcher and the reader. To truly understand it you need to experience it and be inside it. As a general guide, reflection is about exploration and walking around things, the very thing we do a lot of in the classroom. It is like looking through a magnifying glass; some things are reduced in focus, others enhanced. As teachers, we encourage children to look at their experiences from different angles and increasingly ask children to examine their own learning. However, for children to become effective reflectors in your classroom, you yourself need a deep understanding of reflection in the classroom and how it can be used as a tool to aid skills such as analysis, evaluation and creativity, as well as vice versa.

Reflection is a process that is personal and erratic. We all reflect on things in different ways and that can depend on the context, emotion, level of involvement and our previous experiences in addition to many other variables. It does not follow a set pattern, hence it cannot be taught but only encouraged and supported under the right conditions in the classroom. Reflection is concerned with the process and not the product and many theorists put the process at the centre of their research by considering levels of reflection.

Activity

Consider how you reflect as an adult. Choose a recent event, such as a birthday, a journey, a shopping trip. Write down a reflection on this event and then answer the following questions.

- Is this just a broad description or have you included detail?

- Have you analysed the event, raised questions?

- Have you learned anything from this event?

Levels of reflection

Reflection is like appreciating a piece of art or literature and looking at the levels of meaning there. To effectively reflect in this way, children need a structured framework which guides them and helps you to plan for learning through reflection. The research focus below offers one such framework.

Research Focus

Hatton and Smith (1995) provide an academic construct of levels of reflection. Although the levels are hierarchical and indicate progression to deeper levels, they are not intended to be followed in a particular order, as you can enter and leave reflective activity at any level. The levels have been annotated here to focus on children reflecting. However, the original text has also been included in places as it is important that you as a teacher understand how reflection works for different audiences.

Descriptive writing

This can be done orally with children of any age individually, in groups or as a whole class. It is not reflective, it is simply describing an event, action or lesson. For example: Children in Key Stage 1, sitting on the carpet, are being asked: ‘Can anyone tell me what you have been doing in our maths lesson today?’

Descriptive reflection

This is not only a description of an event, action or lesson but some attempt to provide reasons for how things went. For example, ‘I found those sums easy because I used unifix.’

Dialogic reflection

‘Demonstrates a “stepping back” from the events/actions leading to a different level of mulling about, discourse with self and exploring the experience, events, and actions using qualities of judgements and possible alternatives for explaining and hypothesising’ (Hatton and Smith, 1995, p.48). For example: children thinking about why one prefers using unifix to help with their addition and someone else prefers using a number line; talking to each other about this.

Critical reflection

‘Demonstrates an awareness that actions and events are not only located in, and explicable by, reference to multiple perspectives but are located in, and influenced by multiple historical, and socio-political contexts’ (Hatton and Smith, 1995, p.49). For example, children realising that there are many reasons for their choice, such as what the teacher provided, how they learn best; what has influenced their choice – the school, class, friends; thinking about how others learn and even what other equipment children might use in various countries.

The tools of reflection

Bloom’s taxonomy

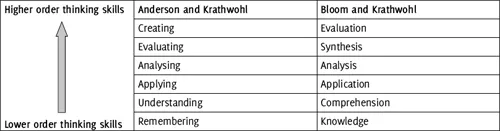

In order to guide children in the varying levels of reflection, you need to support the development of some of the higher order thinking skills in the cognitive domain of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom and Krathwohl, 1956). The model systematically classifies the processes of thinking and learning and was revised and updated by Anderson and Krathwohl in 2001. The revision renamed the skills and transposed the top two higher order skills. As both versions are used in education, both are detailed here (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Thinking skills (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001; Bloom and Krathwohl, 1956)

Understanding

To remember or have knowledge of a situation or event is not the same as understanding it. The two must go hand in hand for learning to take place. A good example of this is learning by rote: the knowledge is there but the reasoning and understanding may not be. Learning times tables is important but alongside this children must be taught how to manipulate numbers and understand them. Therefore understanding of this knowledge is essential.

These are useful terms to help you think about encouraging understanding alongside knowledge acquisition.

- Interpret

- Outline

- Discuss

- Explain

- Describe

Understanding has a key role to play, as children’s reflection is concerned with exploration, thinking and questioning, which all have the potential to lead to increased comprehension.

Analysing

This is a key tool in reflection and can be taught in an appropriate way to any age group. Analysis of an event or aspect of an event may seem a rather academic term to use when discussing children’s learning. However, this is only because of the academic context the word is usually placed in. By exploring what analysis means, you can identify activities that can help to develop this skill in children.

These are useful terms to help you think about analysis in the classroom.

- Examine

- Compare

- Contrast

- Explain

- Investigate

- Identify

Analysis features in each of Hatton and Smith’s levels from ‘descriptive reflection’ onwards, increasing in depth at each stage. Day-to-day learning objectives will often have analytical elements, but to make reflective learning explicit children must have structured opportunities to develop these skills. If you are asking children to ‘investigate’ as part of their learning objective, then ensure your planning provides appropriate opportunities for investigative learning.

Activity

Look at the list of terms linked to analysing. Think about a potential activity for Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2. Then write a series of questions that will help develop their skills of analysis and therefore deepen their reflection.

One example for the activity above is to think about ‘comparing’. A Key Stage 1 class may be looking at a variety of art images and you could ask the question – How is this picture similar to that picture?

Evaluation

Evaluation is viewed by many as one of the easier skills despite its being ranked as one of the higher order processes in the taxonomy. The reason for this would appear to be the misunderstanding about what evaluation entails. It is more than having an opinion or stating what could be improved; it is concerned with making judgements and defending them with reference to set criteria and/or evidence.

These are useful terms to help you encourage the children to think about evaluation in the classroom.

- Justify

- Debate

- Assess

- Determine

- Judge

The use of evaluation in children’s reflection links to Hatton and Smith’s ‘critical reflection’ as demonstrated with the earlier example of why children may have a preference for particular resources to support their mathematics. ‘Critical reflection’ asks children to make judgements, justify the possible reasons and determine why certain choices are made. This can also include debates, presenting opinions/viewpoints and deciding on the criteria for judging a competition.

Creating

This skill links directly into creative thinking, discussed later in the chapter. Young children are better at synthesising or creating information and this needs further encouragement as children get older.

These are useful terms to help you think about how to encourage children to create in the classroom.

- Imagine

- Devise

- Create

- Compose

- Invent

Reflection involves looking at events from different perspectives and this is encouraged through using creative and open thinking. Examples of this skill include asking children to devise a new language or code to write a secret message, or to invent a machine for a task. At first glance these appear to be ‘fun’ activities but in order for children to succeed they will have to use their skills of comprehension, application and analysis first – which makes a seemingly ‘fun’ activity into quite a challenging one.

Primary-aged children reflecting

Young children are concerned with themselves and their needs; they think and act in a subjective manner. This way of thinking allows them to get to know themselves, their likes and dislikes, emotions and strengths. It is an innate process of reflection that often takes place subconsciously and enables children to adjust their perceptions and future reactions to experiences. As children develop they are taught to see situations and events from others’ perspectives as well as their own – beginning the journey from a subjective to an objective frame of reference.

Reflection requires being honest in your own thinking and an ability to question your experiences and perspectives, which can lead to a greater understanding about a situation, alternative approaches and solutions to problems. The move from the subjective to the objective stance supports the reflective process but care must be taken not to confuse reflection with critical thinking, as this will discourage essential creativity and emotional engagement.

Research Focus: Internal and external dialogue as a means of reflection

For the purpose of this chapter internal dialogue is framed within the concept of reflection and in the educational sphere. Speech and talk were discussed in the Introduction and this research focus develops the notion.

There are two forms of dialogue: external and internal. Each can take many forms and be for a variety of purposes, including: incidental, conversational, analytical, evaluative, and emotional. An external dialogue is with another individual or group; an internal dialogue is a conversation with yourself, a place where decisions are made and choices evaluated. Hatton and Smith (1995) found that greater dialogic reflection was evident when students interacted with critical friends. Ballantyne and Packer (1995) indicated that students perceived one of the main weaknesses of journal writing to be its solitary nature. Internal dialogues can range from simple exchanges about whether your husband will notice if you buy another pair of shoes to more profound debates about where you stand in relation to a political or religious issue. These exchanges arise in everyone but some people engage with them on a more conscious level than others. This internal dialogue can be recognised and continued as an aid to decision-making or motivation, or it can be ...