![]()

PART I

PSYCHOTHERAPY AND COUNSELLING OUTCOME RESEARCH

Despite the fact that psychotherapy and counselling are scientific methods of treating psychological and psychiatric problems and disorders, they are also considered as a sort of social care that is hardly recognised as a treatment. This is stressed, though less so in recent years, by some opponents of psychotherapy and counselling outcome research. The fact that what is happening in the therapeutic relationship cannot be captured in naturally reductive scientific inquiry leads to scepticism about the value of outcome and other research. Furthermore, studying therapeutic outcomes is potentially threatening for therapists, if it shows that their work is not that effective. So, why bother studying whether psychotherapy works?

There may be several reasons. In practice, psychotherapists often form their own creative ways of working with clients. Many psychotherapeutic theories were developed on the basis of clinical experience, reflection and cautious reasoning. Counselling and psychotherapy outcome research allows for the assesment of such theories. Similarly, outcome research assesses both approaches that exist and approaches that are developed as a variation on existing therapies due to the limitations of the original approaches with certain types of client. Outcome research may also assess approaches that are developed on the basis of process or other psychological research. Generally speaking, outcome research assesses therapeutic approaches that researchers consider to be potentially effective and therefore worth studying. It is a means of evaluating and validating the effectiveness and efficacy of psychotherapy and counselling. Outcome research often assesses the effectiveness and efficacy of a psychological treatment against alternative forms of treatment, such as pharmacotherapy or self-help groups. Costs are taken into consideration in these instances too.

Psychotherapy and counselling outcome research involves many stakeholders. Among them founders of different therapeutic approaches. They, as well as the therapists trained in their respective approaches, are substantially interested in having their approach empirically validated so that they can gain security in the therapy market. Other stakeholders are the training providers in the various therapeutic approaches. In many countries, the trend is to fund only the training that provides empirically based treatments. Outcome research is very relevant to another group of stakeholders – practising therapists – who may want to know what kind of approach could be promising in their work with a particular client.

Other potential stakeholders are politicians or insurance companies that decide what kind of treatment will be provided in state-funded or insurance-funded medical care. These stakeholders will naturally be cautious when assessing the effectiveness and efficacy of psychotherapy and counselling, as the funds for medical care are always tight and come under many competing pressures. Last but not least, an important group of stakeholders are clients, the consumers of psychotherapy and counselling. They are definitely entitled to know what kinds of effects they can expect from any psychological treatments they are about to undergo.

All these different expectations, interests and pressures influence how psychotherapy and counselling outcome research is conducted. There is a demand for high ethical standards so that findings are not consciously or unconsciously distorted.

![]()

1

Instruments Used in Psychotherapy and Counselling Outcome Research

What the goal of psychotherapy and counselling should be is often the subject of theoretical debate. For example, some approaches favour improvement in psychopathological symptoms, some changes in interpersonal functioning and biographical self-understanding, and some the pursuit of individuals’ potential and personal development. The issue may be further complicated by a particular ethical perspective weighting the impact of different changes achieved in therapy (see Tjeltveit, 1999), e.g. the goals of treatment when working with real guilt.

This chapter will take a pluralistic approach, presenting targets for measuring therapy outcome regardless of their theoretical origin. The main guideline will be ‘current’ practice and currently used instruments. By this, however, I do not want to underestimate any particular context of how change is understood, which definitely influences how therapy is conducted and studied. I will not focus here on generic issues of measurement such as the reliability or validity of the instruments used (see Kaplan & Sacuzzo, 2005), but rather on issues more specific to therapy outcome.

Measuring therapy outcome is a complex matter not only because of problems with the delineation of areas we want to improve by therapy but also because of the complexity involved in quantitatively assessing whether enough change has occurred. This complexity arises from the fact that different methodological approaches to measuring differ in their sensitivity to the amount of change.

Furthermore, different therapeutic approaches may be differentially effective in different areas of therapeutic outcome. For example, two therapies for depression may be differentially effective, with one being more effective in reducing symptoms of depression and other more effective in the area of improved interpersonal functioning. Globally, we could say that the outcome measured may not only be the function of therapy, but also the function of the construct (variable) that is being assessed, its sensitivity to change (or the sensitivity of the instrument that was used), the perspective taken (client, therapist, expert, significant other, objective data, etc.), and the time of assessment (e.g. at the end of treatment vs. follow-up).

Before we move on to introducing different methods of measuring outcome, we will briefly focus on a quantitative expression of the magnitude of change, the so-called effect size (see Cohen, 1988) and criteria that tell us when we can talk about reliable and clinically meaningful change.

Effect Size and the Magnitude of Change

Effect size, in the context of measuring psychotherapy outcome, is a numerical expression of the difference between the means of two or more compared groups as measured by an outcome measure. It includes comparisons of outcomes within the same group, before and after therapy, as well as comparisons of different groups after therapy, e.g. a group of patients receiving psychotherapy and a control group without therapy. Effect size allows us to be more specific about the magnitude of observed change (if it is present) than just simply stating whether the groups differ or not. In psychotherapy research, Glass (see e.g. Smith, Glass & Miller, 1980) adapted Cohen’s d to allow the magnitude of difference between the experimental and control group to be measured. Mathematically speaking, we are using the following formula:

where

ES means effect size,

is the mean of the experimental group,

is the mean of the control group, and the standard deviation

s is computed as the pooled standard deviation of both groups’ distributions (sometimes the standard deviation of the control group is used).

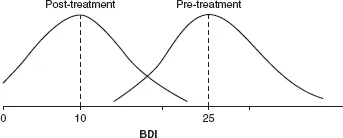

I will illustrate the computation of effect size by using a simple example. Let us suppose that we have a group of depressed patients with the mean score before treatment of 25 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (the possible range of the score is from 0 to 63) and that the standard deviation of distribution of patients’ score is 7. After treatment, the group’s score is 10 on the BDI and the standard deviation would, let’s suppose, remain the same.

To compare the difference measured by the BDI before and after treatment, we replace

in the formula above with the group mean before the treatment and

with the group mean after the treatment. Then we put the pooled mean of both standard deviations into the denominator (to make it easier, let’s suppose it would be 7). The effect size is then 25 minus 10 divided by 7, which is 2.14. This is a large difference according to Cohen’s categorization of effect sizes in social sciences, where an effect size greater than 0.80 is considered large, 0.50 as medium and less than 0.20 as small (Cohen, 1988). The example is graphically presented in

Figure 1.1. As can be seen, the distributions of the score before and after treatment overlap minimally.

Figure 1.1 Distributions of BDI scores of our illustrative example with the pre-treatment mean score 25 (standard deviation 7) and post-treatment mean score 10 with the same standard deviation

The above formula can also be used for comparing two different patient groups, e.g. an experimental and a control group, or two groups in two different active treatments (i.e. two experimental groups). In this case,

stands for the mean of one group and

for the mean of another group, with

s computed as the pooled standard deviation of both groups. Use of the above formula assumes that both groups have almost identical parameters before treatment (means and standard deviations). A more conservative method computes pre-post ESs for both groups separately; the difference between the ESs for the first and second group is then considered the magnitude of difference between groups, hence the ES comparing these groups (see Elliott, 2002b).

Effect size has a broad use. Besides allowing for a more exact estimation of the difference between the groups compared, it also allows the magnitude of effect sizes across several studies to be measured. Thus it can be a basis for the meta-analysis of the cumulative results from several studies investigating outcome (I will address this issue in Chapter 4, which focuses on meta-analysis).

Reliable Change and Clinical Significance

Effect size expresses the magnitude of difference obtained using a particular instrument when comparing two groups, usually experimental and control. It does not, however, tell us whether the outcomes gained by individual patients are also significant in real life. The mean for a particular patient group can, statistically, significantly improve; however, this may not mean that the patients are no longer depressed. Statistically significant change can, for example, be an improvement in the group mean from a score of 25 on the BDI to a score of 20, which would mean that patients are on average still depressed. Therefore, if we want to assess change relevant to patients’ real-life situation, we should be asking whether the patients in a particular treatment are no longer depressed after the treatment.

Whether change occurred, and how big this change is, is usually assessed against two criteria (Jacobson & Truax, 1991: (1) the score of a particular patient on a particular measure must move from the range of dysfunctional population to the functional range; and (2) this change must exceed the measurement error. For example, a patient who filled out the BDI repeatedly would not always achieve the same scores. The score is related to the reliability of the measure, i.e. the stability of measurement and how this measurement is affected by random errors. To say that an individual patient has really improved, his or her score after therapy has to differ from the score before therapy enough to exceed the estimated interval of measurement error. The index determining that the change is sufficiently reliable (i.e. it is not only the effect of random error) is called Reliable Change Index (RCI) (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) and is computed according to the following formula:

where x1 means pre-therapy score, x2 means post-therapy score, and Sdiff is the standard error of difference between two scores that can be computed using the standard error of measurement according to the formula:

where SE means standard error of measurement (we can compute it from the test–retest reliability of the measure and standard deviation of normative data). If the reliable change (RC) is greater then 1.96, then the probability that the post-therapy score expresses the real change is high (i.e. it exceeds the conventional interval of 95%).

As I mentioned above, the fact that change is real (not random) is usually not enough. We also need to know if the change is sufficient, i.e. that it is relevant in regard to the problem that was addressed by therapy. We can assess the relevance of change by the fact that the score after therapy not only really differs from the score before therapy, but that it is more likely to belong to the range of the healthy, non-clinical (e.g. not depressed) population than to the clinical (e.g. depressed) one. Jacobson and Truax (1991) suggest three ways of testing that the change which exceeds random error is clinically significant:

| (1) | The score after therapy should fall outside the range of dysfunctional population, i.e. to the range of two standard deviations beyond the mean for that population (i.e. in direction to the functionality). |

| (2) | The score after therapy should fall within the range of two standard deviations of the mean of the functional non-clinical population. |

| (3) | The score after therapy is closer to the fu... |