![]()

1

The social sciences in modern research

Thou shalt not sit With statisticians nor commit A social science.

W.H. Auden1

[N]o public policy can be developed, no market interaction can occur, and no statement in the public sphere can be made, that does not refer explicitly or implicitly to the findings and concepts of the social and human sciences.

Björn Wittrock2

We live now in a world without frontiers to the unknown, one intensively-investigated planet with a pooling civilization, converging cultures, a single mode of production, and a fragile but enduring peace between states (if one still marred by inherently temporary imperial adventures, civil wars, ethnic divisions, dictatorial excesses, and governance collapses). Human societies also operate within a single global ecosystem, from whose patterns of development there is (and can be) no escape. Perhaps the single best hope for the survival and flourishing of humanity lies in the development of our knowledge – about ‘natural’ systems; and about the complex systems that we have ourselves built and the ways in which we behave within them. The scope of systems on Earth that are ‘human-dominated’ or ‘human-influenced’ has continuously expanded, and the scope of systems that are ‘purely’ natural has shrunk – to such an extent that even the climate patterns and average temperatures across the planet are now responding (fast) to human interventions in burning fossil fuels.

This is the essential context within which the social sciences have moved to an increasingly central place in our understanding of how our societies develop and interact with each other. The external impact of university research about human-dominated and human-influenced systems – on business, government, civil society, media and culture – has grown enormously in the post-war period. It is entering a new phase as digital scholarship produces knowledge that is ‘shorter, better, faster, free’. The social sciences play a key and more integrated role in contemporary knowledge development. Yet the processes involved in social science research influencing wider decision-making have been relatively little studied in systematic ways, and consistently under-appreciated by observers outside academia. Within universities themselves scholars in other discipline groups have also been consistently and often vocally sceptical, especially physical scientists and technologists, whose central roles in knowledge development is already universally recognized and (mostly) lauded.

This book is an attempt to redress this past neglect and to re-explain the distinctive and yet more subtle ways in which the contemporary social sciences now shape and inform human development. It is based on a three-year research study of UK social science, which on most indices and for most disciplines is ranked either second in the world (to the US), and sometimes first (BIS, 2011). In objective world terms the UK is a small island of 60 million people – but in academic terms it can yet punch above its weight, and not least in the social sciences.

Britain is also a mature advanced industrial country, with a stable (perhaps inflexible) system of governance and political process, a services-dominated economy with a vibrant civic culture and media system. These generally favourable background conditions set up very neatly some of the key problems in the funding, organization and transfer of academic knowledge into other spheres of the economy and society. While the UK is in no sense ‘typical’ of anywhere else in the world, it is none the less a case study with many lessons for elsewhere. Britain as a medium-sized country is large enough not to face the ‘group jeopardy in world markets’ problem that sustains exceptional academic and societal cooperation in the small economies of Scandinavia. At the same time it does not have the ‘imperial’ reach of the US’s or (now) China’s political systems and corporations, a scale and exceptionalism that creates distinctive problems and opportunities in the interactions between universities and external actors. Finally, Britain inherently sits within a European civilization and society (much broader than the country’s recurrently disputed membership of the European Union). In Europe the practices of higher education institutions have converged rapidly over the last two decades, partly on an Anglo-American model. So although our focus is primarily on UK social science, the impacts that we chart here play out on EU, wider European and international scales. The issues we discuss are far from being only domestically focused.

We begin by defining what we count as the social sciences, and scoping out how large this field of academic endeavour is in the UK, in terms of resources and the numbers of academics and students involved. The second part concludes our scene-setting by discussing in a preliminary way how the social sciences fit into the wider analysis of ‘human-dominated’ and ‘human-influenced’ systems, and the burgeoning inter-connection of knowledge that such complex systems encourage and necessitate. If we are to understand academic research contributions it is vital that we have schemas and concepts in mind that are attuned to contemporary realities, and not defined by the entrenched mental silos of disciplines, professions and universities.

1.1 The scale and diversity of the social sciences

For historical reasons, the social sciences are often defined

as the disciplines that are in between the humanities

and the natural sciences. As a result, the decision

on which disciplines are parts of social sciences and

which are not varies a great deal from one country to

another and over time.

Françoise Caillods and Laurent Jeanpierre3

Any discipline with science in its name, isn’t

Ron Abrams

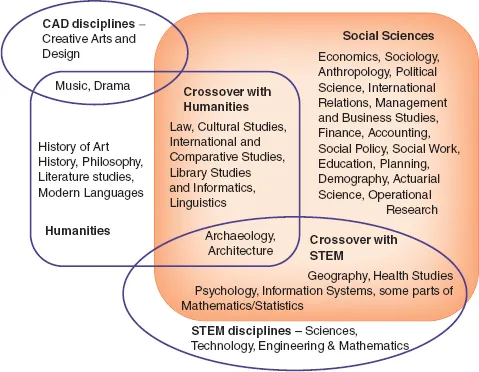

Most of the core social sciences with the strongest ‘scientific’ aspirations (such as sociology and economics) do not have science anywhere in their name. Even in political science there are scholars who insist on a broad ‘political studies’ label still, while other analysts distinguish between a wider, eclectic mass of ‘political scholarship’ and its vanguard area ‘political science’ (Dunleavy, 2010). The social science discipline group also spans across a very wide range of subjects shown in Figure 1.1, some of which make many, and others relatively few, claims to scientific practice. Many social sciences overlap extensively with the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) discipline group. Here, our focus includes strong ‘social’ sub-disciplines within wider disciplines such as psychology, geography, health studies, information systems and archaeology. The most qualitative modes of enquiry occur in large sub-fields that are centred and rooted in social science theories and analytic or quantitative methods, yet that also stretch into the humanities discipline group, including law, history, philosophy and modern media analysis.

What unites the disciplines grouped as social sciences in Figure 1.1? The key common features are:

• They focus on the study of contemporary human societies, economies, organizations and cultures, and their development.

• The intellectual spine of all these subjects is provided by formally set out theories, normally developing logically consistent ‘models’, often utilizing mathematical notation, but always with distinct rules and logics of theory development.

• They focus a great deal on systematically collecting data and information using well-worked out and rigorously tested methods, with most branches making significant use of quantitative data.

• All social sciences look for ‘laws’ of social development, for patterns of association and causation that make sense theoretically and can be evaluated by careful empirical investigation.

• Finally, the social sciences strongly share or seek to emulate standards of good science and of effective scholarship as developed in the physical sciences, stressing the importance of using carefully checked data, analysing data rigorously, replication of information, critical testing of evidence and critical engagement with theories and models, and a conditional acceptance of ‘knowledge’ only to the extent that it survives falsification.

Many sub-disciplines within the Figure 1.1 social science category harbour doubts about one or two of the features above, or contain scholars whose work stresses very informal modes of theorizing, very detailed qualitative work, or authors who emphasize narrative and persuasive writing in their scholarship. But such variation does not qualify the common features above. And wherever disciplines use quantitative data and analysis, ‘digital scholarship’ methods, formal theoretical statement, or social theory as their intellectual spine, their identity as social sciences seeking ‘laws’ of social development is especially apparent.

We shall use the core discipline group labels in Figure 1.1 repeatedly across the rest of the book:

• the STEM disciplines – the (physical) sciences (including medicine), technology, engineering and mathematics;

• the CAD disciplines – creative arts including design, art, film, drama, some forms of media, and creative writing;

• the humanities; and

• the social sciences.

These categories seem obvious, in some sense sanctified by recurrent usage and myriad variants of ‘similar discipline’ groupings enshrined in university organization across the world. Most universities and governments also denominate the physical sciences more carefully. In government’s case this is because it is these disciplines that receive the lion’s share of funding, so a boundary has to be drawn. The longer-established physical science professional organizations (like the Royal Society in the UK) have long played an important role in determining government policies and priorities. Yet still, a report by the Science and Technology Select Committee of the House of Commons (STSC, 2012) found considerable difficulties in defining what constituted STEM subjects. The MPs pointed out the need for concerted action by government and university groups to agree on a common definition of STEM subjects. To go further in firming up any of the four discipline groups above is still surprisingly difficult because of an absence of any well-developed official or government categorizations. Systematic statistics can only be produced when such typologies are fully and stably elaborated. So the problems that we tackle here for the social sciences are not unique to them.

To characterize UK-based social science research, we set out to determine the number of staff active in research across the discipline group, the numbers of post-graduate research students, and the financial resources flowing into the university sector both from government funding and from non-academic external sources. Because building up such a well-quantified picture in a reliable way is not a straightforward undertaking, the sketch of the scale and diversity of social science research as a discipline group that we provide here is littered with ‘rule of thumb’ approximations or assumptions that are eminently contestable. We offer it as a preliminary picture only.

Our key source is the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), which has collected data for many years from British universities on numbers of university research staff and post-graduate research students, as well as other supplementary figures, such as the monies spent on research grants from external funders to universities. Collating standardized information of this kind is supposed to be the core competence of HESA, yet it is still not possible to reach what we might call a definitive set of figures on the number of academic research staff working in social science disciplines. Whereas HESA collects data on the numbers of students studying particular social science disciplines, they do not collect equivalent data on the areas in which staff do research (and teach). They record only the subject disciplines in which staff received their highest qualification. In this format, they ask universities to provide a primary subject discipline for their researchers, and then also give a sub-discipline or a secondary discipline where applicable, in order to narrow down their field of expertise. For example, a political scientist may specialize in public policy or a researcher may have qualified in computer science, but minored in sociology. These data give a reasonably layered picture of the qualification background and expertise of researchers. But they do not provide an accurate picture of the disciplines in which researchers are currently or primarily working. Some degree of estimation is therefore inherent in our numbers.

HESA also does not collate together in any standard way a discipline group for the social sciences, opting instead for a large number of highly specific subject or single discipline labels. So we have had to decide which HESA categori...