- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Health and Well-being in Early Childhood

About this book

The health and well-being of children is integral to learning and development but what does it actually mean in practice?

This textbook draws on contemporary research on the brain and mind to provide an up-to-date overview of the central aspects of young children's health and well-being – a key component of the revised EYFS curriculum.

Critically engaging with a range of current debates, coverage includes

- early influences, such as relationships, attachment (attachment theory) and nutrition

- the role of the brain in health and well-being

- the enabling environment

- other issues affecting child development

To support students with further reading, reflective and critical thinking it employs:

- case studies

- pointers for practice

- mindful moments

- discussion questions

- references to extra readings

- web links

This current, critical and comprehensive course text will provide a solid foundation for students and practitioners on a wide range of early childhood courses, and empower them to support and nurture young children's health and well-being.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Health and Well-being in Early Childhood by Janet Rose,Louise Gilbert,Val Richards,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Brain development – the foundation for adaptive behaviour

Chapter Overview

This chapter introduces the reader to the wonders of our brains. It shows why all those who work with young children need to have an understanding of basic brain structure and function. It provides an insight into the neuroanatomy of the brain and the functional and maturational development pathways. In doing so, it will explore the physiological and psychological relationships between brain, body and mind and highlight the recursive and contingent connections between them. It also introduces the role of relationships and how interactions inform behaviours, which can inform early years practice and support the promotion of children’s health and well-being.

Why study the brain?

Have you ever wondered why some people seem to thrive in their lives while others seem to just survive? The survive or thrive outcomes were thought to be controlled by an individual’s innate temperament and intelligence, or to develop from the opportunities of life experience. However, increasing collaborative research between neurosciences, behavioural sciences and education has questioned this traditional nature or nurture debate as too simplistic. It does not account for the complexity of human experience (Lewkowicz, 2011).

We now know that the brain is biologically programmed to support survival and to do this it follows a recognisable maturational development pattern. However, while our brains have similar basic structural components and common physiological processes, each brain is distinctive in its actual design and function. Neither genetics nor experiences can fully explain how each and every one has different behaviours and outcomes (Ridley, 2004). We live in a socially constructed world, and how we engage with information to sustain integration and achieve our goals influences the structure and function of our brains (Lewkowicz, 2011). Continual and recursive interactions with environmental, experiential and biological factors shape development trajectories, and it is in childhood that the brain is most receptive and malleable (Shonkoff and Garner, 2012).

The terms mind and brain are often used interchangeably. However, the mind should be seen as the product of the active processing of the flow of information in the brain. The brain filters, identifies and synthesises information to construct the mind, which then translates data into programmes of behaviour that are expressed through speech and actions (Greenfield, 2002). It is the cumulative interactions of the brain, mind and body that define our individuality. Therefore, as the mind is a metaphysical concept and it is challenging to objectively measure the relationship between it and the brain, we will examine both in subsequent discussions.

There is an increased scientific and educational consensus on how brains develop, function and are affected by environmental and relational experiences, and it is now considered important for those working with early years to have sufficient knowledge of the brain to support effective practice (Trevarthen, 2011a). To explore this idea further it is useful to use an analogy with something we are all familiar with and take as integral to our own lives and society: the car.

There are three levels of knowing cars. Most of us engage at level one: we know how to drive cars, know it has an engine that provides the power to move the car, and that cars are useful and integral to modern life. Some of us know cars at level two: these are the enthusiasts who know some of the basic components of an engine and understand what they need to work (for example, a car needs oil that needs changing periodically), know how to sustain performance (such as checking tyre pressure), know about common faults and can carry out basic repairs (such as changing a tyre). Then there are those at level three: the mechanics and engineers (the experts), who we turn to because of their specialised knowledge and professional skills to diagnose and treat any problem that we encounter. Most car users have some understanding of basic car maintenance but have to turn to a specialist to solve any problems that arise through wear and tear, misuse or poor maintenance. However, being an enthusiast enables you to independently sustain optimum performance and know when you need to seek specialist help.

The same can be said about caring for our brains: the brain is the engine that drives our lives. By being an enthusiast of the brain we can develop a more holistic understanding of child health and well-being. As an enthusiast, we can have an awareness of the basic structural anatomy and physiology of the brain, know how the brain and mind develop and how they connect intramentally (solitary thinking) and intermentally (communicating with others) (Rushton et al., 2010), and understand what influences performance and development (Zambo, 2008). This new knowledge about the brain will support professional confidence to create and sustain the environments and experiences that nurture children’s learning (Immordino-Yang, 2011). Furthermore, given the correlations that appear to exist between health and well-being and economic outcomes, there is increased financial imperative for practitioners to recognise the functional relationships between the physical, social and psychological dimensions of human development (Trevarthen, 2011a). Practitioners need to feel competent in critically evaluating the credibility of research from many disciplines that purports to improve and sustain universal health and well-being, and particularly its relevance to effective practice. A clearer knowledge and understanding of the brain will help us to do this.

The brain

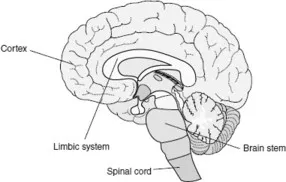

A typical adult’s brain has been described as ‘big as a coconut, the shape of a walnut, the colour of uncooked liver and the consistency of firm jelly!’ (Carter, 2010: 38) The brain is made up of two cerebral hemispheres on the right and left that are joined together by an information highway, known as the corpus callosum. The corpus callosum allows information to travel between the two hemispheres and it is believed that our perceptions and memories are products of the information that is shared between the left and right cerebral hemispheres (Cozolino, 2014). Brains are complex systems that have an innate self-organising capacity to balance the specialisation of areas with the connectivity of the whole in order to optimise brain efficiency and functional capacity (Siegel, 2012). We will divide the brain into three main areas, the brain stem, the limbic system and the cortex and briefly explore the structural features and functions of each of them in turn (see Figure 1.1 of the brain sliced vertically in half). For a more detailed explanation, see the suggested further reading list at the end of the chapter.

Figure 1.1 Areas of the brain

Mapping the brain

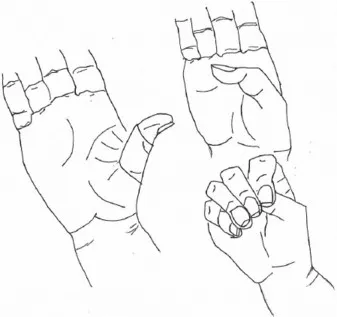

Siegel (2012) has a very useful model which can help us visualise and better understand the situation of the different parts of the brain and how they are connected to one another. All you need is your arm and hand! Roll up your sleeve to reveal your model of the brain and central nervous system. Imagine that your arm is the spinal cord and that your hand is your brain. Now tuck your thumb across the palm of your hand and curl your fingers around it, making a fist, as shown in Figure 1.2. This is a now a simple 3-D representation of how the different regions of the brain are positioned and we can now explore how the different areas of the brain.

Your arm and wrist: the spinal cord

All the messages from our muscles, internal organs and senses continuously travel up the spinal cord to the brain. In the brain, the information is decoded, prioritised and combined with previous knowledge, before being passed back down to inform a response in the muscles and organs. This to-ing and fro-ing of information happens consciously and unconsciously and is a process integral to our behaviours, whether we are awake or asleep, physically very active and engaged or sitting quietly and day-dreaming.

Figure 1.2 Hand model of the brain (Siegel, 2012)

(Illustrated by Christopher Walker)

Your hand: lower part of the palm: the brain stem

Your hand is joined onto the arm at the wrist and opens out into a palm. Imagine that the palm of your hand is the brain stem. The brain stem is where the nerves run up and down the spinal cord to join the brain (Figure 1.1). It is involved in unconscious (autonomic) functions, including the levels of alertness, breathing, heartbeat and blood pressure (all vital for living). The brain stem also facilitates the fight–flee mechanism – an essential survival response – which will be discussed in the next chapter.

Your hand: lower part of the back of the hand: the cerebellum

The cerebellum (see Figure 1.4) is involved in integrating the sensory information passing into the brain, redirecting information to the different areas of the brain and controlling gross and fine motor movements as well as being involved in attentional levels and problem-solving (Badenoch, 2008).

Your thumb: the limbic system

The limbic system is contained deep within the centre of the brain (your thumb is tucked away in the centre of your fist and surrounded by your hand), and so is referred to as being subcortical. It includes: the amygdala, the hippocampus, the cingulate cortex, the hypothalamus and the thalamus (see Figure 1.3). These specialised regions are not functionally mature at birth but are genetically primed to develop and connect as a result of relational experiences with primary caregivers (Badenoch, 2008). The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, is involved in prioritising behavioural responses to real or perceived threats for survival. It continuously receives, assesses and responds to external (environmental) and internal (organ status) information by comparing and combining streams of information coming into the brain with previous experiences that are stored as conscious (known) and unconscious (unaware) memories. It operates largely unconsciously and is significant to learning, motivation, memory, feelings and expressions of emotio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Table List

- Acknowledgements

- About The Authors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Brain development – the foundation for adaptive behaviour

- Chapter 2 Brain processes in health and well-being

- Chapter 3 The Stress Response System in Supporting Health and Well-Being

- Chapter 4 Nutrition in Health and Well-Being

- Chapter 5 Attachments and Early Relationships

- Chapter 6 Emotional Development and Regulation

- Chapter 7 Active Learning

- Chapter 8 Emotion Coaching

- Chapter 9 Resilience and Building Learning Power

- Chapter 10 Economic and Social Factors Affecting Health and Well-Being

- Chapter 11 Early Intervention in Health and Well-Being

- Chapter 12 Conclusion: Sustainable Health and Well-Being

- References

- Index