![]()

PART 1

INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

![]()

1 | THE LANGUAGE OF METHODOLOGY |

In Chapter 1 you will meet a text which aims at clarifying the connections between various main concepts of methodology and their relationships. Those concepts are central to any understanding of different scientific ways of approaching problems and possibilities to create business knowledge in a number of areas.

METHODOLOGY

Methodology is no easy subject, but the more exciting as it concerns one’s own personal development as a researcher, consultant or investigator in one direction or another. It is also a relatively young subject, at least in the subject of business. There are contributions to its development, for instance, from philosophy, sociology, logics and mathematics. This, our book about methodology, was, when it appeared in its first edition, one of the first attempts ever to clarify the meaning of methodology in business. Now you hold the third edition in your hand.

Methodology is a mode of thinking, but it is also a mode of acting. It contains a number of concepts, which try to describe the steps and relations needed in the process of creating and searching for new knowledge.

METHODOLOGICAL VIEWS

In business, there are a number of views on when and how to use methods for studying and researching reality. There are also a number of opinions on what is really the meaning of “methods”. Let us refer to these opinions as methodological views and later we will become more precise about what this might mean in various contexts. Our precision does not seek to define any kind of “best practice”, but to disclose the complexity of this field, hoping to simplify as well as to clarify the choice of methods available to anyone trying to research the area of business.

Box 1.1

When Methodological Views “Talk and Act”

It is a common use of language to depersonify different social phenomena. We say, for instance, that “research has shown” …, etc. Of course there are people (researchers) behind these statements. When we in the future talk in terms of “the view assumes”, “the view looks at”, etc., we use the same way to express ourselves for practical reasons. However, it is not the views in themselves, but their proponents who act and therefore carry full responsibility for what the view stipulates.

The different methodological views make certain ultimate presumptions beforehand about what we study as business researchers, consultants or investigators. These presumptions differ between views, and the different views, therefore, present different ways to understand, explain and improve. Even if the differences are not as drastic as to compare the starting points of the different views to historical opinions about the configuration of the Earth – flat, round, oval or square – this might nevertheless illustrate what we mean.

If we believe that the Earth is flat, our observations and statements will be based on this belief (as we know, there are historical proofs of this). Our models of, say, navigation, will be concerned with avoiding sailing over the edge, etc. Those who, at that time, started with the assumption that the Earth was round then gained a competitive advantage, of course, by being able to navigate to areas, which were assumed to be placed outside the so-called “edge”.

Another interesting parallel is found in what the New York Times once wrote about the rocket pioneer professor Goddard set against a recent quotation from the Kennedy Space Centre in the USA. In the New York Times they wrote in 1921: “Professor Goddard does not know the relation between action and reaction and the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react. He seems to lack the basic knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” And in 2006, it was possible at the Kennedy Space Center to read the following quotation from Goddard: “It is difficult to say what is possible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.”

The reason why we have chosen the historic perspective is explained by the fact that it is not until afterward, when we are no longer tied to those assumptions which led to the statements, that we can verify whether they (and thereby the views behind them) have been fruitful or not. We must therefore not be tempted to brush aside the illustrations above by saying, “Oh well, now we know better”, because what we know today will probably be known better, or rather, differently, tomorrow.

One more example of how different assumptions may block understanding is found in Watson’s (1969) book The Double Helix. This describes his and Crick’s discovery of the DNA-molecule. When competing to solve the riddle they were convinced that they would get there before other researchers. Their main competitor was, in Watson’s words, “so stuck on his classical way of thinking that I would accomplish the unbelievable feat of beating him to the correct interpretation of his own experiments”. So, the assumption of the old way of thinking prevented their main rival from interpreting his own actions correctly!

It is relatively easy, afterwards, to see how some assumptions are blocking a successful interpretation in the case of the shape of the Earth, conditions for launching a rocket and the discovery of DNA in the natural science area. It is more difficult in the social area. Such clear cases are more or less non-existing there. Instead, all ingredients are mixed as in a big soup: a soup which is floating around in our brains while at the same time as we must judge its content, consistency and taste in order to create new business-oriented and evolutionary recipes.

By this we want to say that it is only speculatively and reflectively (not logically or empirically) possible to overcome historical verification. From this it follows that there will be problems comprehending the data we collect or try to explain/understand unless we have already reflected upon how the particular view will shape our observations, our understanding and our explanations. As methodological views have different characteristics, it stands to reason that in business, as in other social sciences, there are disagreements between proponents of different views. This situation indicates the necessity of a critical attitude from the readers’ side in relation to different views to avoid being deceived into believing that applying a methodological view in different situations is without conflicts.

It is necessary in these situations to clarify to yourself whether it is of interest to develop business knowledge in order to discover what is possible in our world of possibilities. This is even more important if you want to develop models and theories to bring into business as tools/processes adapted to your own situation in order to, for instance, reconfigure a market or create new business-oriented advantages in an existing market, or create completely new markets.

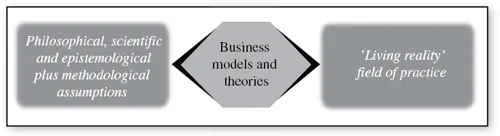

business, with its models and theories, is characterized not only by its close relationships to these kind of “philosophical assumptions”, but also by its near relationships to “practical reality” where businesses are developed and conducted. This situation is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Close Connections

In this book we have chosen to talk about this search for knowledge in terms of knowledge-creating. The reason why we have chosen “create” instead of other concepts like construct or develop is not directly related to how we think that knowledge arises. Knowledge may arise from pure guessing or speculations, through shifts of perspectives, from critical thinking and via anomalies. Knowledge may also be the result of careful planning and field studies, through decoding of information and from simple arithmetic, through experiments, and more. The common denominator in all this is that somebody consciously takes on something in order to disqualify existing knowledge, or confirms existing knowledge or enlarges it, that is, that somebody in a critical, conscious and insightful fashion creates the prerequisites for generating knowledge. This person we have chosen to call a creator of knowledge or knowledge creator (see Box 1.3 below). Included in this meaning is also the assumption that this is a person who can consciously and stringently stick to the rules, but also, if necessary, creatively transgress them.

Box 1.2

Why Can’t We “Just” Collect Data and Make Statements?

In order to develop business theories and models, methodological views make different assumptions about the reality they try to explain and/or understand. This, in turn, means that observations, collections of data and results are determined to a large extent by the view chosen. Conscious development of knowledge in business – as in other subjects – is therefore far from “just” collecting data and making statements. (Even an “unconditioned” mushroom picker has ideas of where the most sought after mushrooms may grow.) What might be essential data to one view can be completely irrelevant to another. For instance, what value would a calculation of the probability of falling over the edge have for proponents of the Earth being a globe? To take another example: what statistical use does a researcher, who is statistically searching for only what is general as knowledge about, say, entrepreneurship, have for the results of another researcher, who is searching for what is unique in the entrepreneurially single cases? Can the very search for what is general and what is unique reflect/reveal other ultimate presumptions as well – presumptions about life, reality and business venturing, which are influencing when, where and how we are searching for knowledge and what, we are searching for? And, not to mention, why we are searching at all? We are convinced it does!

Box 1.3

To be a Creator of Knowledge

When are we creators of knowledge, say, within the subject of business? We want to restrict the concept to cover only when such work of developing knowledge and being creative is based on conscious assumptions of reality, and when we understand what knowledge is and how it comes about. Unconscious and naive consultative and investigative activities rarely lead to more than simply confirming what we know already. We have seen this kind of cookbook knowledge develop too often to neglect its existence. In this book we reserve, therefore, the concept of creator of knowledge to mean what we refer to a conscious researcher, consultant or investigator.

METHODOLOGY AND REALITY

Methodological views make ultimate presumptions about reality! But what does that actually mean? Even to attempt to investigate, explain and understand reality we make certain assumptions about its quality, what it is like. These assumptions become a guide for the creator of knowledge in his or her effort to research reality.

The assumptions about reality guiding the creator of knowledge (see Box 1.3) can be conceived as kinds of background “philosophical” hypotheses, but not in the sense that they can be tested empirically or logically, as each view has already postul...