- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comparative-Historical Methods

About this book

This bright, engaging title provides a thorough and integrated review of comparative-historical methods. It sets out an intellectual history of comparative-historical analysis and presents the main methodological techniques employed by researchers, including:

- comparative-historical analysis,

- case-based methods,

- comparative methods

- data, case selection and theory.

Matthew Lange has written a fresh, easy to follow introduction which showcases classic analyses, offers clear methodological examples and describes major methodological debates. It is a comprehensive, grounded book which understands the learning and research needs of students and researchers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Comparative-Historical Methods: An Introduction

Since the rise of the social sciences, researchers have used comparative-historical methods to expand insight into diverse social phenomena and, in so doing, have made great contributions to our understanding of the social world. Indeed, any list of the most influential social scientists of all time inevitably includes a large number of scholars who used comparative-historical methods: Adam Smith, Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Barrington Moore, Charles Tilly, and Theda Skocpol, are a few examples. Demonstrating the continued contributions of the methodological tradition, books using comparative-historical methods won one-quarter of the American Sociological Association’s award for best book of the year between 1986 and 2010, despite a much smaller fraction of sociologists using comparative-historical methods.

Given the contributions made by comparative-historical researchers, it is apparent that comparative-historical methods allow social scientists to analyze and offer important insight into perplexing and pertinent social issues. Most notably, social change has been the pivotal social issue over the past half millennium, and social scientists have used comparative-historical methods to offer insight into this enormous and important topic. State building, nationalism, capitalist development and industrialization, technological development, warfare and revolutions, social movements, democratization, imperialism, secularization, and globalization are central processes that need to be analyzed in order to understand both the dynamics of the contemporary world and the processes that created it; and many—if not most—of the best books on these topics have used comparative-historical methods.

Despite the great contributions made by comparative-historical analyses of social change, there is very little work on exactly what comparative-historical methods are. Unlike all other major methodological traditions within the social sciences, there are no textbooks on comparative-historical methods; moreover, present books reviewing comparative-historical analysis touch on methods only briefly, focusing most attention on the types of issues analyzed by comparative-historical scholars and important figures within the research tradition. Thus, comparative-historical methods have produced some of the best works in the social sciences; many of the best social scientists use them to analyze vitally important social issues, but there is little discussion of what such methods actually are.

This omission is unfortunate for comparative-historical analysis; it is also unfortunate for the social sciences in general. Indeed, the works and issues analyzed by scholars using comparative-historical methods have dominated the social sciences since their emergence, so an understanding of comparative-historical methods helps improve our understanding of the entire social scientific enterprise. Moreover, comparative-historical methods—as their name implies—are mixed and offer an important example of how to combine diverse methods. Given inherent problems with social scientific analysis, combining methods is vital to optimize insight, but competition and conflict between different methodological camps limit methodological pluralism. Comparative-historical methods, therefore, offer all social scientists an important template for how to gain insight by combining multiple methods. Finally, yet related to this last point, comparative-historical methods also offer an example of how to deal with another dilemma facing the social sciences: balancing the particular with the general. The complexity of the social world commonly prevents law-like generalizations, but science—given the dominance of the natural sciences—privileges general causal explanations. The social sciences are therefore divided between researchers who offer general nomothetic explanations and researchers who offer particular ideographic explanations. Comparative-historical analysis, however, combines both comparative and within-case methods and thereby helps to overcome this tension, and to balance ideographic and nomothetic explanations.

In the pages that follow, I help to fill the methodological lacuna surrounding comparative-historical methods. This book is not meant to be an overview of everything comparative and historical; rather, using broad strokes, it paints a picture of the dominant methodological techniques used by comparative-historical researchers. For this, I summarize past methodological works, review the methods used in past comparative-historical analyses, and integrate all into a single statement about the methodological underpinnings of comparative-historical analysis. In so doing, I also offer new interpretations of what comparative-historical methods are, their analytic strengths, and the best ways to use them.

Defining Comparative-Historical Analysis

Comparative-historical methods are linked to a long-standing research tradition. This tradition was previously referred to as comparative-historical sociology, but Mahoney and Rueschemeyer (2003) refer to it as comparative-historical analysis in recognition of the tradition’s growing multidisciplinary character. In addition to sociology, comparative-historical analysis is quite prominent in political science and is present—albeit much more marginally—in history, economics, and anthropology.

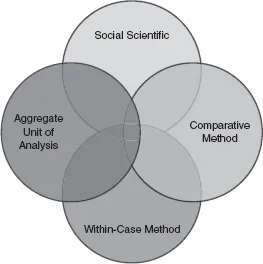

As the Venn diagram in Figure 1.1 depicts, comparative-historical analysis has four main defining elements. Two are methodological, as works within the research tradition employ both within-case methods and comparative methods. Comparative-historical analysis is also defined by epistemology. Specifically, comparative-historical works pursue social scientific insight and therefore accept the possibility of gaining insight through comparative-historical and other methods. Finally, the unit of analysis is a defining element, with comparative-historical analysis focusing on more aggregate social units.

A methodology is a body of practices, procedures, and rules used by researchers to offer insight into the workings of the world. They are central to the scientific enterprise, as they allow researchers to gather empirical and measurable evidence and to analyze the evidence in an effort to expand knowledge. According to Mann (1981), there is only one methodology within the social sciences. It involves eight steps: (1) formulate a problem, (2) conceptualize variables, (3) make hypotheses, (4) establish a sample, (5) operationalize concepts, (6) gather data, (7) analyze data to test hypotheses, and (8) make a conclusion. He suggests that the only methodological differences in the social sciences are the techniques used to analyze data— something commonly referred to as a method. Because particular techniques commonly require particular types of data, methods are also linked to different strategies of data collection.

Figure 1.1 Venn diagram of comparative-historical analysis

All works within comparative-historical analysis use at least one comparative method to gain insight into the research question. By insight, I mean evidence contributing to an understanding of a case or set of cases. As described in considerable detail in Chapter 5, common comparative methods used within comparative-historical analysis include narrative, Millian, Boolean, and statistical comparisons. All of these comparative methods compare cases to explore similarities and differences in an effort to highlight causal determinants, and comparative-historical analysis must therefore analyze multiple cases. Although some comparative methods offer independent insight into the research question, others must be combined with the second methodological component of comparative-historical analysis: within-case methods.

Within-case methods pursue insight into the determinants of a particular phenomenon. The most common within-case method is causal narrative, which describes processes and explores causal determinants. Narrative analysis usually takes the form of a detective-style analysis which seeks to highlight the causal impact of particular factors within particular cases. Within-case analysis can also take the form of process tracing, a more focused type of causal narrative that investigates mechanisms linking two related phenomena. Finally, comparative-historical researchers sometimes use pattern matching as a technique for within-case analysis. Different from both causal narrative and process tracing, pattern matching does not necessarily explore causal processes; rather, it uses within-case analysis to test theories.

Within-case methods constitute the “historical” in comparative-historical analysis—that is, they are temporal and analyze processes over time. Moreover, they commonly analyze historical cases. This historical element has been a commonality unifying works within the comparative-historical research tradition to such an extent that works using within-case methods that do not analyze historical/temporal processes should not be considered part of the research tradition.

In addition to methods, comparative-historical analysis is also defined epistemologically. Epistemology is a branch of philosophy that considers the scope and possibility of knowledge. Over the past few decades, there has been growing interest in postmodern epistemological views that deny the possibility of social scientific knowledge. They take issue with positivism, which suggests that social scientists can gain knowledge about social relations by using social scientific methods. Instead, the postmodern view suggests it is impossible to decipher any social laws because of the sheer complexity of social relations. These works go beyond Max Weber’s claims that social scientists should pursue verstehen— or understanding—instead of social laws, suggesting that even a limited understanding is impossible. Verstehen is impossible, according to this view, because discourses impede the scientific study of human relations. Most basically, our social environments shape human values and cognitions in ways that severely bias our analysis of social relations and—in combination with extreme social complexity—prevent any insight into the determinants of social relations.

It is not my intention to discuss the merits and demerits of postmodern epistemological views, but such a position necessarily prevents a work from being an example of comparative-historical analysis. In particular, when a researcher denies the ability of social scientific methods to provide causal insight, they are inherently anti-methodological. Further, because methodology is the primary defining element of comparative-historical analysis and because comparative-historical analysis is focused on causal analysis, postmodern works are epistemologically distinct from comparative-historical analysis and should be considered separate from the research tradition.

The final definitional element of comparative-historical analysis concerns the unit of analysis. Traditionally, all works that are considered examples of comparative-historical analysis have taken a structural view and explore meso- and macro-level processes—that is, processes involving multiple individuals and producing patterns of social relations. Along these lines, Tilly (1984) described comparative-historical analysis as analyzing big structures and large processes, and making huge comparisons. As such, states, social movements, classes, economies, religions, and other macro-sociological concepts have been the focus of comparative-historical analysis. This focus does not prevent comparative-historical researchers from recognizing the causal importance of individuals. For example, Max Weber was a founding figure of comparative-historical analysis and paid considerable attention to individuals. More contemporary social scientists using comparative-historical methods also employ individual-level frameworks that consider individual-level action. Both Kalyvas (2006) and Petersen (2002), for example, analyze the causes of violence and focus on individual-level mechanisms. However, in doing so, Weber, Kalyvas, and Petersen all analyze how the structural and institutional environments shape individual actions and, thereby, the actions of large numbers of people. Even when analyzing individual-level processes, therefore, comparative-historical researchers retain a structural focus and consider the interrelations between individual and structure.

While one might justify this final definitional element based on historical precedent, there are practical reasons to limit the category of comparative-historical analysis to works at the meso- and macro-level. Individual-level analyses that do not link individuals to structure are inherently different from the analysis of collective units, as scholars of the latter analyze collective processes and dynamics rather than individual thought processes and actions. Most notably, micro-analysis draws on individual-level data to understand the perceptions, interests, motivations, and actions of a single person and is, therefore, very biographical. Biography can also be an important component of more macro-level analyses, but such analyses also include structural analysis. That is, because meso- and macro-level analysis explores causal processes involving a number of people, it analyzes common structural and institutional factors shaping how large numbers of people act. As a consequence, familial, religious, economic, and political institutions as well as warfare, population growth, and other events that affect the lives of large numbers of people hold prominent positions in comparative-historical analysis.

Using all four defining elements, the size of the body of work that constitutes comparative-historical analysis is greatly reduced, leaving a large body of work that is similar to comparative-historical analysis in several ways but is not an example of it because the work lacks at least one of the four defining elements. Thus, Said’s Orientalism (1978) and other postmodern works that compare cases and use narrative analysis to explore meso/macro-level processes are not examples of comparative-historical analysis because they are not social scientific: they deny the ability to gain insight into our social world through comparative and within-case methods. Similarly, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s (2001, 2002) statistical analyses of colonial legacies are social scientific, analyze macro-processes, and use comparative methods; but they are not examples of comparative-historical analysis because they omit within-case analysis. Next, Tilly’s The Contentious French (1986) offers a social scientific analysis of the French political system through the use of within-case methods, but the book is not a clear example of comparative-historical analysis because it does not gain insight through the explicit use of inter-case comparison. Notably, all three of these are influential works of exceptional quality. By excluding them, I am not suggesting that they are inferior to comparative-historical analysis in any way; they simply do not conform to the main defining elements of the methodological tradition.

Despite my use of a specific definition, the boundaries of comparative-historical analysis are very blurred. Some works clearly use within-case methods to answer their research questions but do not make explicit comparisons that explore similarities and differences. Others use comparative methods to gain insight into their research questions but include brief case studies that offer little insight. Similarly, some researchers question—but do not deny—the possibility of social scientific insight, and some analyses focus primarily on micro-level processes while briefly considering how the structural environments shape the micro-level. Ultimately, I am not concerned with delineating precise cutoff lines because the quality of an analysis is not determined by whether or not it is an example of comparative-historical analysis. Instead, I have defined comparative-historical analysis in an effort to clarify the major elements of the research tradition. A comparison of comparative-historical methods with other major methodological traditions in the social sciences is also helpful in this regard.

Social Scientific Methods: A Review

Comparative-historical methods are one of several methodological traditions used by social scientists in their efforts to understand our social world. In this section, I briefly review the major social scientific methods—statistical, experimental, ethnographic, and historical—and compare them to comparative-historical methods. I conclude that comparative-historical analysis employs a hodge-podge of methods and therefore has affinities with almost all other methodological traditions. Indeed, the main distinguishing characteristic of comparative-historical analysis is that it combines diverse methods into one empirical analysis that spans the ideographic-nomothetic divide.

Nomothetic/Comparative Methods

Different methodological traditions take a positivistic approach and attempt to provide nomothetic explanations of social phenomena. That is, they pursue insight that is generalizable and can be applied to multiple cases. At an extreme, nomothetic explanations pursue law-like generalizations that apply to the universe of cases, something implied by its name (“nomos” is Greek for law). Given the dominance of the natural sciences and their ability to offer insight that applies to the universe of cases, nomothetic explanations are commonly—but incorrectly—viewed as more scientific, so researchers who attempt to make the social sciences as scientific as possible commonly pursue this type of explanation. Rarely, however, do they go to the extreme of pursuing social laws that apply to the universe of cases, believing that extreme social complexity makes social laws impossible. So, instead of exploring the causes of ethnic violence in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, these works explore common determinants of several episodes of ethnic violence, but they rarely try to discover a cause of all episodes of ethnic violence.

Methods pursuing nomothetic explanations necessarily analyze multiple cases because it is impossible to generalize based on one or a few cases. Although a researcher might simply...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Author

- Chapter 1 Comparative-Historical Methods: An Introduction

- Chapter 2 An Intellectual History and Overview of Comparative-Historical Analysis

- Chapter 3 The Within-Case Methods of Comparative-Historical Analysis

- Chapter 4 Within-Case Methods and the Analysis of Temporality and Inter-Case Relations

- Chapter 5 The Comparative Methods of Comparative-Historical Analysis

- Chapter 6 Combining Comparative and Within-Case Methods for Comparative-Historical Analysis

- Chapter 7 Data, Case Selection, and Theory in Comparative-Historical Analysis

- Chapter 8 Comparative-Historical Methods: Conclusion and Assessment

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Comparative-Historical Methods by Matthew Lange,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.