- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Work with Children, Young People and their Families in Scotland

About this book

This fully-updated and revised third edition addresses the changes to law and practice in relation to adoption and permanency, the children's hearing system and the implications of the provisions of the Children and Young People (S) Act 2014 and other related matters, including the National Practice Model of GIRFEC. This is the only text to provide coverage of the new legal, policy and practice landscape of social work with children and families in Scotland, and as such, it is an indispensable guide for students, newly-qualified social workers, managers and practice teachers and a range of other professionals in health, education, the police and others in cognate disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Work with Children, Young People and their Families in Scotland by Steve Hothersall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Contexts for practice: Law, policy and society

Achieving a Social Work Degree

This chapter will help you to address elements from within the Scottish Standards in Social Work Education (SiSWE) (Scottish Executive, 2003a, available at: www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2003/01/16202/17015).

- Key Role 1: Prepare for, and work with, individuals, families, carers, groups and communities to assess their needs and circumstances.

- 1.1 Preparing for social work contact and involvement.

- Key Role 4: Demonstrate professional competence in social work practice.

- 4.1 Evaluating and using up-to-date knowledge of, and research into, social work practice.

- 4.2 Working within agreed standards of social work practice.

It will also assist you in working towards achieving elements within the four domains of the Key Capabilities in Childcare and Protection – Effective Communication; Knowledge and Understanding; Professional Confidence and Competence; Values and Ethical Practice (Scottish Executive, 2006e, available at: www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2006/12/13102807/0).

Introduction

This chapter will discuss a number of important issues regarding the relevance of and interrelationships between law, policy and social work practice. You may well ask what law and policy have to do with you as a student of social work. The answer is simple: law and (social) policy affect practice at almost every turn and, in its turn, practice, as a mediated response to social need, influences the evolution of policy and in some instances the law, as the government of the day responds to promote the general and collective good through social policy.

Law and policy are a reflection (accurate or otherwise) of society's attempts to regulate human conduct and promote general well-being. The legal and policy frameworks which relate to social work can guide and assist in making sense of what is going on and in many ways assist in determining what can and should be done in particular circumstances. For example, if a child is suspected of having been the victim of abuse, society (via law and policy) determines what the general response to that should be in the form of making available certain powers and procedures to effect their protection. In tandem with this are the knowledge, values and skills of the social worker that actually make things happen. In this respect, law and policy frames what you do as a worker, but how you do it is largely down to you. Thus, you must engage with law and policy, as these are the ‘rules of the game’ so to speak. Using this analogy think for a moment of a game/sport you are familiar with – let's say football – and imagine that you thought you knew the rules, but then someone on the pitch suddenly picked up the ball and began to run with it. If you didn't know the rules of that game, how would you know that what they were doing was not allowed? In order to play the game, you have to know the parameters within which it should properly take place. It is no different in professional practice. A practitioner who is not up to date with relevant law and policy and suitably aware of the practical effects of these is a potentially dangerous practitioner.

However, what is done and how it is done is affected by the social context. For example, we are now more aware of the impact of parental substance misuse upon children and the responses we ought to make towards this in terms of social work action. Law and policy are mediated by society's understanding of this as a phenomenon. Therefore, how society perceives a particular issue at any given time provides the broad practice context within which you work and we shall consider this below as the third element in this complex relationship.

The law then is the framework within which your practice must take place. If your practice were to operate outside of this framework, you would be acting illegally, so that cannot happen. As we have already mentioned, some laws are quite specific to your practice and in fact dictate what you may or may not do in any given circumstance. Other laws are quite circumspect and offer the opportunity for interpretation based upon professional judgement (Taylor, 2012; Munro, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2012b).

Law is invariably aligned to regulations, policy and guidance that does some of the interpreting for you and these also act as a guide to practice as well as being vehicles through which the law is enacted. There are also policies issued by agencies, having national policy and legislation as their basis, which will also affect you and what you do and how you do it.

For a thorough grounding in relation to social work law in Scotland see Guthrie (2011) and for a more technical account of the law in relation to children and the family see McK Norrie (2013a), and for a more general discussion of the law as it relates to social work in England and Wales (although many of the themes and issues are of relevance to your practice in Scotland), see Johns (2011).

The (Much) Wider Picture

This book is about social work with children, young people and their families in Scotland. It is however necessary to be aware of the influences of the broader international, European and UK socio-political contexts (Bonoli and Natali, 2013; Hemerijck, 2012; Clarke, 2004; Esping-Andersen, 2006) even though Scotland now has a devolved Parliament (Leith et al., 2012; Cohen, 2002) and its own distinct policy system (Mooney and Scott, 2012; Hothersall and Bolger, 2010). This section will give you a brief overview of the Scottish legal system, the Scottish Parliament and the1 functions of the Scottish Government as well as introducing you to the relationship between politics and the policy process within Scotland.

1 The Government in Scotland was previously referred to as the Scottish Executive until it changed its name to the Scottish Government in May 2007.

All law within the UK must be compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms 1950 (ECHR) (incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK)) as well as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) of which the UK is a signatory. Any domestic (Scottish or UK) law which does not subscribe to the principle of compatibility has to be reviewed or if it is applied it will be void. By default, policy provision must also render itself compatible with the broad principles of the two conventions referred to above and, in the same way, so must your practice.

Within the UK there is the constitution, headed by the Sovereign, which comprises many rules and procedures, both written (statute law and case law) and unwritten (for example, common law) which determine how the country is governed and how the different institutions within society should relate to each other. This constitutional law derives its authority from convention, legislation and judicial decisions and from some other sources like the writings of institutional writers like Erskine, Hume and Stair who are considered, certainly within Scots law, to be authoritative.

The Parliament of the UK is comprised of the Sovereign, the House of Lords and the House of Commons. Between them they provide a government, which generates legislation (laws) and policy and regulations to support these. The subsequent legal system(s) that have emerged, civil and criminal, serve to regulate our conduct by providing a framework of rules that aim to promote cooperation within society. By their existence, these rules set up a series of expectations against which society can determine (by and large) whether our obligations to each other and to society at large are being fulfilled by reference to notions of reasonableness/legality and unreasonableness/illegality.

The criminal law in Scotland (Ferguson and McDiarmid, 2013) provides sanctions or penalties against those who fail to comply with its terms. The standard of proof required to determine that the criminal law has been broken is that of beyond reasonable doubt. For example, in a situation where it is claimed that Mr Smith threw a stone through your window but he denies this, if several people had witnessed the event and someone had filmed it close up, this type of evidence would be sufficient to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he was the culprit. In civil law, where a wrong is claimed to have been done by one against another (delict) the courts or a tribunal (like the children's hearing) may arbitrate and the standard of proof here is on the balance of probability, which means that the wrong was more likely to have been done as claimed than not. For example, Mrs Smith says that Mr Smith has been unreasonable in his behaviour during the course of their ten-year marriage and she wants a divorce. Mr Smith says that he hasn't and refuses to agree. In court, evidence might include Mrs Smith's friend who says that she has heard Mr Smith shouting at his wife and Mrs Smith's own testimony would also be taken into account, as would that of Mr Smith. This may be sufficient to prove, on the balance of probability, that Mr Smith has been unreasonable enough for the court to grant the divorce.

In social work with children, young people and their families in Scotland, most (but not all) of the law you will refer to will be civil and will be dealt with either through the Sheriff or the High Courts or a tribunal, most often the children's hearing. Where a child is harmed by a parent, redress would be through civil proceedings under the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 (see McK Norrie, 2013b) to afford protection, but if it was thought that a criminal offence had been committed (sexual/assault), then the relevant criminal law would apply in relation to the alleged perpetrator and would be dealt with, at least initially, through the Sheriff Court. Thus, in complex situations like child abuse, both strands of the law would operate.

The Scottish Context

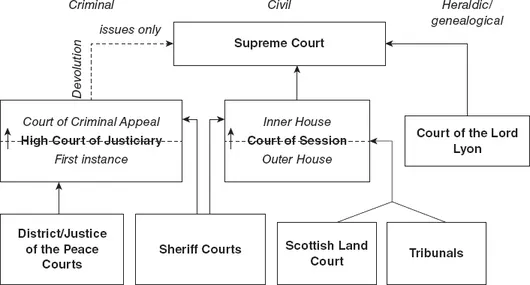

Figure 1.1 The Court Structure in Scotland, Including Tribunals

Some civil and criminal laws operate UK-wide although there are differences in relation to their operation in Scotland as well as some laws that are specific to Scotland. If you look at Figure 1.1, you will notice that the highest criminal court in Scotland is the High Court; there is no right of appeal to the Supreme Court in Scotland in relation to criminal matters as there is in England and Wales, although civil matters can be referred to the Supreme Court in Scotland. The names of the courts are also different. In England and Wales there are Magistrates' Courts, Crown Courts, the High Court, Courts of Appeal and the Supreme Court. In Scotland, there are District Courts, Sheriff Courts and the High Court and judges are called sheriffs. The High Court in Scotland acts as both a trial court and an appeal court and if it is felt that there has been a miscarriage of justice, there is recourse to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Tribunal which has the power to refer cases back to the Appeal Court for consideration. There are also two different procedures in Scottish courts: summary procedure, which means that the sheriff will hear the case sitting alone; and solemn procedure, which means that the sheriff or judge (in the High Court) will sit with a jury of 15 people. As the name implies, solemn procedure is used in more serious matters and in all appeals.

Legislation and Policy in Scotland after Devolution

To where does a Statute Refer?

Any Act or document that relates specifically to Scotland will usually have that name in the title (e.g. Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011). General Acts of the UK which are/were UK-wide will be identified here (suffix UK) as will general Acts relevant only to England and Wales (suffix E and W) or to Wales (suffix W) or to Northern Ireland (suffix NI). In the interests of brevity, the full title of Scottish Acts will be given with (Scotland) abbreviated to (S). Each Act or document will then be referred to as ‘the 2011 Act’, etc. unless there is more than one Act with the same date, in which case the specific title will be given.

Scotland now has its own devolved Parliament that came into existence following the granting of Royal Assent to the Scotland Act on 19 November 1998. Prior to this, and as a direct result of the Act of Union of 1707, there had only been one Parliament in the UK, located at Westminster which had legislated for England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales although the general affairs of Scotland (and Northern Ireland and Wales) have had some form of representation through their respective Offices. In the case of Scotland this was the Scottish Office, headed by a UK Government Minister with the title of Secretary of State for Scotland. During the latter part of the twentieth century, however, concessions were made by the Westminster Parliament that granted limited powers to the other countries within the UK and Regional Assemblies were formed in Northern Ireland and Wales, although their powers are not as clearly devolved as those in Scotland are now. This process of devolution, which is the delegation of central government powers to a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Introduction to Third Edition

- Chapter 1 Contexts for practice: Law, policy and society

- Chapter 2 Working with and Providing Support to Children, Young People and their Families

- Chapter 3 Working together: Collaboration, Integration and Effective Practice

- Chapter 4 The Children's Hearings System and Youth Justice

- Chapter 5 Safeguarding and Child Protection

- Chapter 6 Looked after and Accommodated Children and Young People, Adoption and other Forms of Permanency

- Appendix: The Standards in Social Work Education and the Key Capabilities in Child Care and Protection

- References

- Index