- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Key Concepts in Political Communication

About this book

This is a systematic and accessible introduction to the critical concepts, structures and professional practices of political communication.

Lilleker presents over 50 core concepts in political communication which cement together various strands of theory. From aestheticisation to virtual politics, he explains, illustrates and provides selected further reading. He considers both practical and theoretical issues central to political communication and offers a critical assessment of recent developments in political communication.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Key Concepts in Political Communication by Darren G Lilleker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

Communication between the ruling organisations of a society and the people is central to any political system. However, in a democracy, political communication is seen as crucial for the building of a society where the state and its people feel they are connected. Political communication must, therefore, perform the role of an activator; it cannot simply be a series of edicts to society from the elite, ruling group but must allow feedback from society and encourage participation. While some may argue that a regular vote is sufficient for a nation to be termed democratic, this could also be described as a dictatorship with a finite term. Modern democracies need to be increasingly responsive to their publics, and at the heart of responsiveness is a dialogue. Classic definitions of political communication focus on the source and the motivation; political communication flows out from the political sphere and must have a political purpose. However, such definitions would not be completely appropriate for many modern states, particularly given the role of the media. Therefore modern texts focus on three actors, some of whom operate beyond the boundaries of any single state, each of whom produce political communication. These are, firstly, the political sphere itself: the state and its attendant political actors. Their role is to communicate their actions to society in order to gain legitimacy among and compliance from the people. Secondly, there are the non-state actors, where we would include a range of organisations with political motivations as well as corporate bodies and, of course, the voters. Each of these organisations and groups communicate messages into the political sphere, in the hope of having some level of influence. Finally, there are the media outlets, the media communicates about politics, influencing the public as well as the political spheres. In a free, open and pluralist society, on which the majority of texts concentrate, each of these communicates independently but synergistically with one another. In other words, they say what they want when they want but are influenced by one another and may well be led by one particular group when formulating arguments, opinions, policies, perceptions or attitudes.

Despite the academic study of political communication being a fairly young discipline; the actual practice is as old as politics itself. Just as Pope Innocent III ordered his minions in England in 1213 to nail what was known as a papal bull, a poster bearing the seal of the pope, to church doors informing the English of the excommunication of their king, John; modern politicians use all the available media to deliver messages to the people. The example of King John’s excommunication is pertinent, albeit dated, as this was one of many times when there were forces competing for the support of the people. The Catholic Church used the best method for disseminating a message among faithful churchgoers, the majority of English society at that time, informing them that their king, and therefore kingdom, was no longer recognised by the Church: keep the king and go to hell was the inference. The message was also designed as a warning to King John that another, more suitable, ruler, Philip Augustus, king of France, was allowed sanction to invade. Such communication is prevalent across the world today, between states and within states, at the heart of which is persuasion: that the receiver should act in a way desired by the sender.

Within modern democracies the people elect a person, and usually their party, to run the country for a defined period of time, usually between four and five years. In order that the people can make the choice of who to elect, each competitor must communicate to them effectively. Each competitor tries to persuade the public that they, at what ever level they are standing, from national president to town mayor, are the best for the job. Subsequently, when one or another individual or party is elected, it is essential that they continue to communicate. Some would argue that this communication is central to encouraging democratic culture; it is the provision of information that is required by the people (Denton and Woodward, 1990). However, there are more cynical accounts which argue that the majority of communication from the elected is designed to retain support among the electorate for their policies, what has been termed as ‘manufacturing consent’ (Herman and Chomsky, 1998). Therefore political communication is often placed central to debates on the health and well-being of our democracy and the styles and levels of interaction are often used as a measure of the strength of public approval and engagement in the political system (Blumler and Gurevitch, 1995).

In an ideal world scenario political communication is unproblematic. However, due to a range of developments in the political, social and technological spheres political communication has been forced to change, both in style and in substance. Furthermore, across all democracies, there are a greater number of political voices, both elective and non-elective, competing for the ear of the public. This makes political communication an increasingly complex business, not only as an area of academic study but also in the way it is practiced. This introduction will provide an overview of the types of political communication, their functions and the motivations of those who communicate political messages. The introduction introduces the key concepts explained throughout the book so allowing an understanding of how each concept fits with the context of political communication. Prior to this, however, it is useful to explain the context of democratic politics.

THE DEMOCRATIC STATE

Democratic states are defined by the institutionalisation of free, fair and regular elections that do not debar anyone from participating, whether as voters or candidates, on grounds that are unreasonable: in the 21st century these would include race and ethnic background, gender and political beliefs. Those we elect are our representatives; they use their political power, given by the people through the vote, on behalf of the people. This is the fundamental concept of a representative democracy: to ensure a broad range of people, and their views, are represented; made possible by both state and society supporting pluralism of views and access to the media. Pluralism allows power to be widely dispersed across a number of political groupings with contrasting views, all of whom have access to a largely neutral governmental machine. There are debates on the effectiveness of this system (see Heywood, 1997: 65–82); however, the twin principles of democracy and pluralism predominate in the world.

In a representative democratic state there are various tiers, or levels, of political power. Broadly speaking these can be separated between national and local; however, there are state differences. Some states have at the head of the political system a president, and beneath the president an elected chamber of representatives; these two levels should ensure power is not centralised. Other systems have a parliament led by a prime minister and cabinet government whose party holds power over legislation (lawmaking) but is responsible and accountable to a larger group of representatives, often from a range of other political parties. Below the national government there are a range of regional and/or local tiers of government. These are responsible to national government but are often also elected. Outside of the elected political structure are pressure groups representing those voters who share a single special interest; they can be representatives of workers in one industry, such as trade unions or professional associations, or they may be businesses or industrial representatives. These all compete for representation within the political system and can often be brought into the process of decision making (Grant, 1989). Communication from and between these groups is essential to the health of democracy, though the diffusion of power can mean that their views can remain marginalized and they may be forced to take action that gains them greater attention than they would normally be awarded: workers can withdraw their labour, interest groups can hold demonstrations, marginalized groups can resort to terror tactics. The latter can all be indications of a failure within the system of a pluralist, representative democracy and are a recurrent feature of the modern world.

One further powerful group exists outside of the political system: the broadcast and print media, collectively known as ‘the media’. The media act both as the communicator of political views from all groups in a state and as a watchdog that calls political actors to account for their actions. Their role in society has been both attacked and defended by academics, politicians and journalists alike. Some argue the media is too powerful and promotes an agenda that can be contrary to the interests of a pluralist democracy (Entman, 1996). Alternatively, Norris (2000) argues that the media play an important role in upholding the democratic nature of a society and strengthening pluralism. Others take the view that the media can fall under political control, and so weaken pluralism through offering a biased perspective (Reeves, 1997; Wring, 2001). Finally, there is the view that the media report only what they feel is important, that through the selection of news values, framing and agenda-setting, the public fail to receive sufficient information on which to base their voting decision and some views become excluded due to their lack of fit to the media frames, agendas and values (Schlesinger, 1983; Blumler and Gurevitch, 1995; Said, 2000). What all these accounts agree on is the power of the media in determining what is communicated and what is not, what the public know and what they do not know; thus we hear of a media-centred democracy. The greater the independence enjoyed by the media does not equate to reductions in criticisms from all these perspectives, thus central to most studies of political communication, global or national, is a study of the media due to its centrality to the process of the dissemination of political views, information and knowledge.

It is within this context that these concepts will be explained. These are the individuals and groups we expect to be involved in the process of political communication and, based on their roles, we see a central concern among all actors with ‘being heard’: by each other, by select groups of actors or members of the public, by the mass audience, or by everyone within a society or indeed beyond.

THE HISTORY AND METHODS OF POLITICAL COMMUNICATION

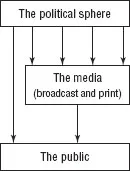

Political communication is as old as political activity; it was a feature of ancient Greece and the Roman Empire as well as across diverse political systems in the modern age. It is hard to think of a time, under any political system, where political leaders have not had a requirement to communicate with other groups in society, or have not had to persuade the people to support them, often as opposed to rivals for their power and position. However, for much of human history political communication would have been a linear, top-down process from leaders to people. This is shown in Figure 1. We see the direction of communication being straight down, the majority being caught by the media and then channelled out once again, what is now referred to as the process of mediation; however little communication was to go from the bottom of society into the political sphere.

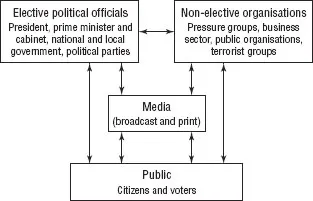

Democratisation of the majority of the political systems changed the nature of political communication and political activity moved into the public sphere. The people became involved in politics because they were expected to have a political role. Equally, with increased access to information and greater levels of education, came a demand for greater political involvement and influence. The voter was not content with the simple act of voting, the voter became an active citizen, one who could join an anti-state cause, the fight against apartheid in South Africa for example, as easily as a recognised political party. Communication between the various groups, electoral and non-electoral, became competitive; each vying for space in the media and the attention of the people. Thus we find more complex models for understanding modern political communication.

Figure 1 A traditional view of political communication

Figure 2 The Levels of Political Communication

Figure 2 demonstrates the lines of communication that, theoretically, are open between each group. How communication is made may vary, and how audible the message is can be dependent upon the size of any group or level of support for a party, group or cause and the tactics used to get the message across. However, in a pluralist society, at least in theory, all groups will communicate among themselves and between one another and will be both learning from and competing with one another.

The greater the number of voices competing, the more intense the competition, the better communicators groups must be in order to be heard. Thus we hear of the professionalisation of political communication, that it has become better in some way in order to be heard by more groups and individuals (Mancini, 1999). Some attribute developments purely to learning from practice in the United States (US), others shy away from the Americanisation thesis; however, most agree that the process by which political communication is carried out has evolved, become more technically and technologically sophisticated and adopted techniques from the worlds of corporate advertising and marketing in order to compete in the modern information-rich society.

An early and effective form of direct, or non-mediated, political communication involved public meetings; political campaigners would go out and meet the workers and deliver speeches to them. It was using these tactics that movements like Lenin’s Bolsheviks gained the support necessary to undermine Russia’s tsar, Nicholas II; equally such meetings allowed the British Labour Party to become an electoral force. Elsewhere, public meetings, in church halls, cinemas or back rooms of hotels, cafes and drinking houses became a key way to meet the people; the memoirs of many democratic politicians, active in the 19th and early 20th century, recall such events during their early careers. The late, veteran United Kingdom (UK) Labour Member of Parliament (MP) Ian Mikardo recalls in his autobiography Backbencher a meeting in the canteen of the Miles aircraft factory at Woodley, just outside Reading, the constituency Mikardo successfully fought in 1945. Here he faced 6,000 workers, all worried about redundancies following the end of the Second World War. To secure their votes, Mikardo had to allay their fears while the workers tried to ‘squeeze all they could out of the first opportunity they’d had in ten years to put some aspiring politician through the hoop’ (Mikardo, 1988: 83). Such meetings are now few and mainly limited to countries where technology does not allow for the message to be delivered directly to homes: the only comparable types of event are the mass rallies held around US presidential elections, or mass meetings of party members.

Technology, however, not only effected political communication in the 20th century. The invention of the printing press allowed Thomas More to attack the inequality in 15th-century England. Since then, every political activist has published pamphlets and often delivered them by hand door to door or placed them in venues where the masses may be reached. While still the preserve of weakly-funded, often radical or underground movements, or those with little access to mass communication media, such activities still take place. Every election across the democratic world will see leafleting, and many argue that such activities are of ultraimportance in determining the result of elections (see particularly the research of David Denver (Denver and Hands, 1997; Denver et al., 2002; see also Johnston, 1987; Negrine and Lilleker, 2003)). But, largely, political communication has become an activity aimed at a mass audience using the mass media of television across the majority of the states in the world today. Hence direct political communication has become less of a feature in recent elections, despite research that indicates the importance of face-to-face interaction between politician and public (Jackson and Lilleker, 2004).

As communications technology allowed mass communication, communication necessarily changed. Many politicians took an instant dislike to the constraints of television: war leaders Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle found it hard to adapt their styles and appeared awkward and aloof in front of the camera (Scammell, 1995). They, and many politicians of their era, had learned how to use radio effectively. In fact, during the Second World War, a secondary communication war took place with national leaders transmitting to their own people, to rally support, while enemies attempted to undermine their efforts by broadcasting into other states. Consider the effect on the people of Sheffield, UK, when the Nazi-supporting broadcaster Lord Haw Haw would ask them to look out of their windows and see if ‘the ten ta...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface and dedication

- Introduction

- How to use this book

- Aestheticisation

- Agenda-Setting

- Americanisation/Professionalism

- Audiences

- Authenticity

- Brands/Branding

- Broadcasting/Narrowcasting

- Campaigns/Campaigning

- Civil/Civic Society

- Consumerism/Consumerisation

- Cynicism

- Dealignment

- Dumbing Down

- E-representation/E-politics

- Electoral professionalism

- Emotionalisation

- Framing

- Globalisation

- Hegemonic Model

- Ideology

- Image

- Information Subsidies

- Infotainment

- Legitimacy/Legitimisation

- Manufactured Consent

- Media-Centred Democracy

- Media Effects

- Mediatisation

- Message/Messages

- Negativity

- News Management

- News Values

- Packaging

- Permanent Campaigning

- Political Advertising

- Political Marketing

- Popular Culture

- Populism

- Propaganda

- Pseudo-Events

- Public Relations Democracy

- Public Sphere

- Representation

- Rhetoric

- Segmentation

- Soundbite/Soundbite Culture

- Source–Reporter Relations

- Spin/Spin-Doctor

- Technological Determinism

- Terrorism

- Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Virtual Politics/Virtual Communities